Cubist fragmentation deconstructs objects into abstracted geometric forms, challenging traditional perspectives and emphasizing multiple viewpoints within a single composition. This technique disrupts realism to explore the complexity of visual perception, inviting deeper analysis of shapes and spatial relationships. Discover how Cubist fragmentation transforms art and influences modern creativity by reading the rest of the article.

Table of Comparison

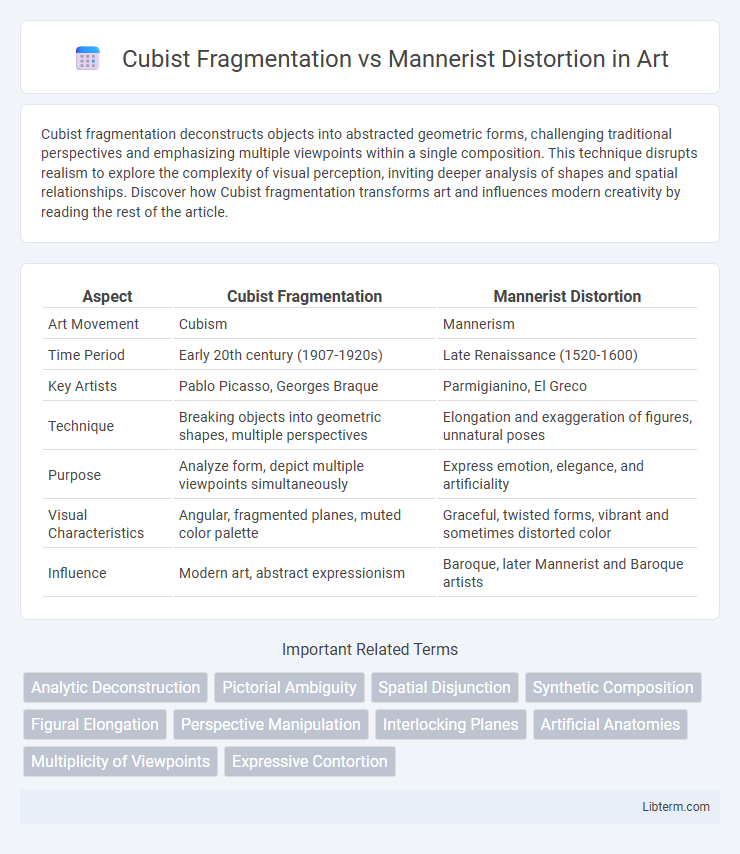

| Aspect | Cubist Fragmentation | Mannerist Distortion |

|---|---|---|

| Art Movement | Cubism | Mannerism |

| Time Period | Early 20th century (1907-1920s) | Late Renaissance (1520-1600) |

| Key Artists | Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque | Parmigianino, El Greco |

| Technique | Breaking objects into geometric shapes, multiple perspectives | Elongation and exaggeration of figures, unnatural poses |

| Purpose | Analyze form, depict multiple viewpoints simultaneously | Express emotion, elegance, and artificiality |

| Visual Characteristics | Angular, fragmented planes, muted color palette | Graceful, twisted forms, vibrant and sometimes distorted color |

| Influence | Modern art, abstract expressionism | Baroque, later Mannerist and Baroque artists |

Introduction to Artistic Deformation

Cubist fragmentation breaks objects into geometric shapes to depict multiple perspectives simultaneously, challenging traditional representation and emphasizing abstract forms. Mannerist distortion alters natural proportions and spatial relationships to evoke emotion and tension, often exaggerating figures for dramatic effect. Both techniques deconstruct realistic imagery but serve distinct artistic intents: Cubism explores fractured reality, while Mannerism intensifies expressiveness through deliberate distortion.

Defining Cubist Fragmentation

Cubist Fragmentation involves breaking objects into geometric shapes and reassembling them on multiple planes to depict different perspectives simultaneously. This technique emphasizes abstract, angular forms to challenge traditional single-point perspective. In contrast, Mannerist Distortion elongates and exaggerates figures to evoke emotional tension rather than deconstructing spatial relationships.

Unpacking Mannerist Distortion

Mannerist distortion emphasizes elongated proportions, twisted poses, and exaggerated gestures to create emotional intensity and complexity, contrasting with the analytical and geometric fragmentation seen in Cubism. This style emerged in the late Renaissance, where artists manipulated human anatomy to evoke tension and instability rather than realistic representation. Mannerist works often display ambiguous spatial relationships, unusual perspectives, and an overall sense of artifice that challenges classical harmony.

Historical Contexts: Cubism and Mannerism

Cubism, emerging in the early 20th century with pioneers like Picasso and Braque, revolutionized art by breaking subjects into geometric fragments, reflecting the modernist quest to depict multiple perspectives simultaneously. Mannerism, flourishing in the late Renaissance around the 16th century with artists like El Greco and Pontormo, emphasized distorted proportions and exaggerated poses as a response to the harmonious ideals of the High Renaissance. Both movements reflect their historical contexts: Cubism mirrors the complexities of a rapidly industrializing and modernizing world, while Mannerism expresses the religious and political tensions of post-Renaissance Europe.

Techniques of Fragmentation in Cubism

Cubist fragmentation techniques involve breaking down subjects into geometric shapes and reassembling them to depict multiple perspectives simultaneously, emphasizing abstract spatial relationships. Artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque utilized faceting and overlapping planes to deconstruct form and challenge traditional single-point perspective. This method contrasts with Mannerist distortion, which exaggerates proportions and gestures for emotional effect rather than spatial analysis.

Methods of Distortion in Mannerism

Methods of distortion in Mannerism emphasize elongated proportions, exaggerated poses, and unnatural spatial relationships to evoke emotional tension and complexity. Unlike Cubist fragmentation, which breaks subjects into geometric facets, Mannerist artists manipulate anatomy and perspective to create unsettling, elegant imbalances. These techniques appear prominently in works by El Greco and Pontormo, showcasing deliberate deviations from classical harmony to intensify expressive impact.

Visual Impact: Comparing Viewer Experience

Cubist fragmentation breaks subjects into geometric shapes, presenting multiple perspectives simultaneously to engage viewers in active visual reconstruction, creating a dynamic and analytical experience. Mannerist distortion exaggerates proportions and elongates forms, evoking heightened emotional responses and a sense of tension or elegance through dramatic visual manipulation. The Cubist approach challenges perception and intellectual engagement, while Mannerist distortion prioritizes expressive intensity and emotional impact on the viewer.

Philosophical Underpinnings of Each Style

Cubist Fragmentation embodies an analytic approach to reality, reflecting early 20th-century critiques of linear perspective and embracing multiple viewpoints simultaneously to challenge classical representations of form and space. Mannerist Distortion, rooted in the late Renaissance, emphasizes exaggerated proportions and dramatic poses to express emotional tension and complexity, highlighting human subjectivity and artistic virtuosity. Both styles explore the perception of reality but diverge in philosophy: Cubism deconstructs form to uncover underlying structures, while Mannerism distorts to evoke psychological intensity.

Influences and Legacy of Both Movements

Cubist fragmentation, influenced by Cezanne's emphasis on geometric forms and African tribal art, challenged traditional perspectives by depicting subjects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, fundamentally reshaping modern art's approach to space and form. Mannerist distortion, rooted in the classical traditions of the Renaissance but exaggerated to express emotion and tension, influenced later Baroque artists and contributed to the development of expressionism by pushing figures into elongated, unnatural poses to evoke psychological complexity. Both movements left enduring legacies: Cubism's analytical deconstruction paved the way for abstract art and visual experimentation, while Mannerism's emotive distortions informed subsequent explorations of human emotion and dramatic composition in Western art history.

Conclusion: Divergence and Convergence in Artistic Innovation

Cubist Fragmentation deconstructs subjects into geometric planes, emphasizing multiple perspectives to challenge traditional representation, while Mannerist Distortion exaggerates proportions and spatial relationships to evoke emotional tension and complexity. Both movements diverge in approach--Cubism prioritizes analytical reassembly and abstraction, whereas Mannerism focuses on expressive elongation and dynamic compositions. Their convergence lies in pioneering artistic innovation by breaking classical conventions, influencing modern art's exploration of form, perception, and emotional depth.

Cubist Fragmentation Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com