Serfdom was a system where peasants were legally bound to a lord's land, providing labor and services in exchange for protection and a place to live. This institution shaped medieval society by limiting personal freedom and reinforcing social hierarchies. Learn more about the origins, impact, and decline of serfdom in the rest of the article.

Table of Comparison

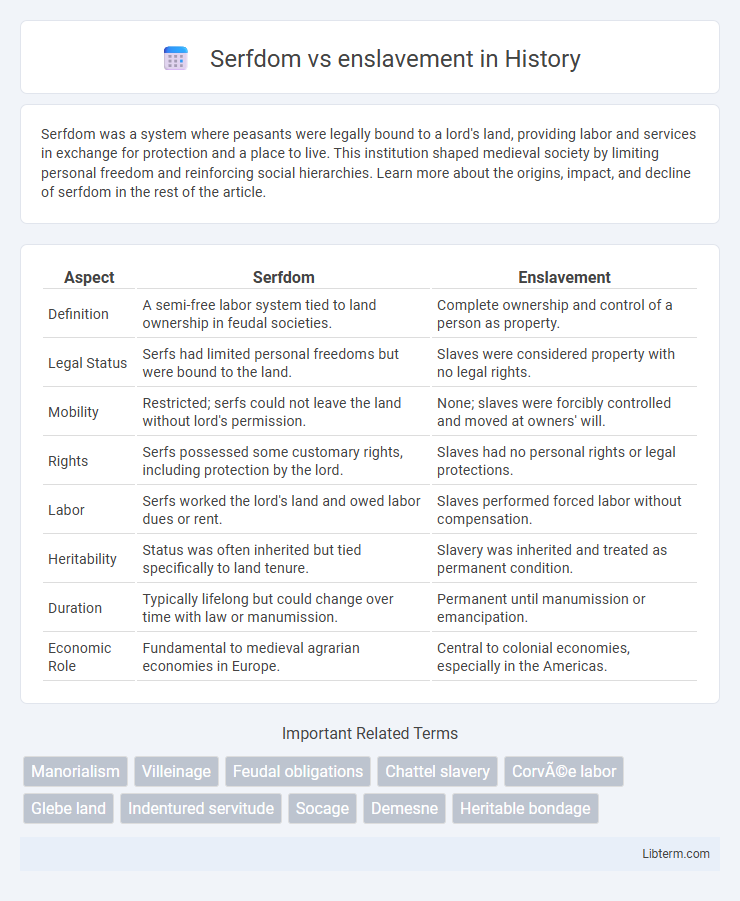

| Aspect | Serfdom | Enslavement |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A semi-free labor system tied to land ownership in feudal societies. | Complete ownership and control of a person as property. |

| Legal Status | Serfs had limited personal freedoms but were bound to the land. | Slaves were considered property with no legal rights. |

| Mobility | Restricted; serfs could not leave the land without lord's permission. | None; slaves were forcibly controlled and moved at owners' will. |

| Rights | Serfs possessed some customary rights, including protection by the lord. | Slaves had no personal rights or legal protections. |

| Labor | Serfs worked the lord's land and owed labor dues or rent. | Slaves performed forced labor without compensation. |

| Heritability | Status was often inherited but tied specifically to land tenure. | Slavery was inherited and treated as permanent condition. |

| Duration | Typically lifelong but could change over time with law or manumission. | Permanent until manumission or emancipation. |

| Economic Role | Fundamental to medieval agrarian economies in Europe. | Central to colonial economies, especially in the Americas. |

Introduction to Serfdom and Enslavement

Serfdom was a medieval socioeconomic system where peasants were legally tied to the land they cultivated, obligated to provide labor and services to a landowner while retaining limited personal freedoms. Enslavement, in contrast, involved complete ownership of individuals as property, stripping them of all rights and subjecting them to forced labor and control under harsh conditions. The key distinction lies in serfs' conditional rights and obligations within a feudal hierarchy versus the absolute domination and deprivation experienced by enslaved people.

Historical Origins and Contexts

Serfdom originated in medieval Europe as a socio-economic system where peasants were bound to the land and obligated to serve a lord, reflecting a feudal structure rooted in agrarian economies. Enslavement dates back to ancient civilizations such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece, characterized by the complete ownership of individuals as property with no personal freedoms. The key historical distinction lies in serfdom's legal ties to land and limited personal rights, versus slavery's absolute deprivation of autonomy and transferable ownership status.

Legal Status and Social Class

Serfdom legally bound peasants to the land, granting them limited rights and obligations to their feudal lords, while enslaved individuals were treated as property with no personal freedoms or legal recognition. Serfs occupied a lower social class but retained familial and some communal ties, whereas enslaved people lacked social status entirely and were subject to complete control by their owners. The legal distinction allowed serfs to maintain certain protections under customary law, unlike enslaved persons who were denied legal personhood and subjected to ownership transfer.

Economic Roles and Obligations

Serfdom involved peasants legally bound to land, required to provide agricultural labor and a portion of their produce to a landlord, supporting the feudal economy through sustained agrarian output and local obligations. Enslavement entailed complete ownership of individuals who performed unpaid labor across various economic sectors, generating wealth primarily through forced, uncompensated work with no personal rights. Economic roles in serfdom stabilized rural economies by maintaining land productivity, while enslavement maximized profit through exploitation and unrestricted control of human labor.

Rights, Restrictions, and Freedoms

Serfdom entailed peasants being legally bound to a lord's land, possessing limited rights such as the ability to own personal property but restricted from leaving without permission, whereas enslavement completely deprived individuals of personal autonomy and any recognized rights. Serfs faced obligations like labor and tribute but retained family and some community ties, while enslaved individuals were considered property, subjected to forced labor, and lacked legal personhood. The freedom of serfs could occasionally be purchased or earned over time, contrasting with enslaved people whose liberation typically required external intervention or escape.

Family Life and Personal Autonomy

Serfdom generally allowed peasants to maintain family units and some personal autonomy, as serfs could live on and work inherited land while owing service to a lord. Enslavement typically stripped individuals of family stability and personal freedom, subjecting them to forced labor without legal rights to marry or keep family members together. The ability to cultivate family life and exercise limited autonomy marked a crucial distinction between the social conditions of serfs and enslaved people.

Mobility and Hereditary Status

Serfdom limited personal mobility, as serfs were legally bound to the land they cultivated, restricting their ability to leave without the lord's permission, yet their status was generally hereditary, passing from parent to child. Enslavement imposed complete mobility restrictions, with enslaved individuals treated as property who could be bought, sold, and relocated at the owner's discretion, and their enslaved status was also inherited by their descendants in many societies. Both systems enforced rigid social hierarchies, but serfs retained some legal protections and communal rights absent in chattel slavery.

Methods of Control and Resistance

Serfdom utilized legal obligations and land tenure systems to bind peasants to the lord's estate, enforcing control through taxes, labor dues, and limited mobility, while enslavement relied on ownership as property, complete physical coercion, and denial of personal freedom. Resistance in serfdom often involved subtle noncompliance, fleeing to towns, or petitioning for rights, whereas enslaved people commonly engaged in outright rebellion, escape via underground networks, and preserving cultural identity as forms of defiance. Both systems imposed severe restrictions, but the methods of control and the nature of resistance reflect fundamentally different power dynamics and social structures.

Abolition and Legacy

Serfdom was gradually abolished in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries, with landmark reforms like the Emancipation Reform of 1861 in Russia, which legally freed millions of serfs while often maintaining economic dependency. Enslavement, particularly in the Atlantic slave trade, faced abolition movements culminating in the 19th century with laws such as the British Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 and the U.S. Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which legally ended chattel slavery but left lasting socio-economic disparities. The legacy of serfdom and enslavement deeply influenced social hierarchies, land distribution, and racial inequalities, with many former serfs and enslaved people facing systemic oppression despite legal freedom.

Comparative Analysis: Serfdom vs Enslavement

Serfdom and enslavement differ fundamentally in legal status and personal freedoms; serfs were bound to the land with limited rights but maintained some personal autonomy, while enslaved individuals were considered property with no legal personhood. Economically, serfs provided labor primarily in agricultural systems under feudal obligations, whereas enslaved people were forced into diverse labor roles with absolute ownership by their masters. The comparative analysis reveals serfdom as a socio-economic structure embedded in medieval feudalism, contrasting with enslavement's complete erasure of personal freedoms and rights across various historical contexts.

Serfdom Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com