Sharecropping is an agricultural system where tenants farm land owned by others in exchange for a portion of the crops produced, often leading to cycles of debt and poverty. This practice shaped rural economies and social structures, especially in post-Civil War Southern United States, impacting labor dynamics and land ownership. Explore the rest of the article to understand how sharecropping influenced economic and social change.

Table of Comparison

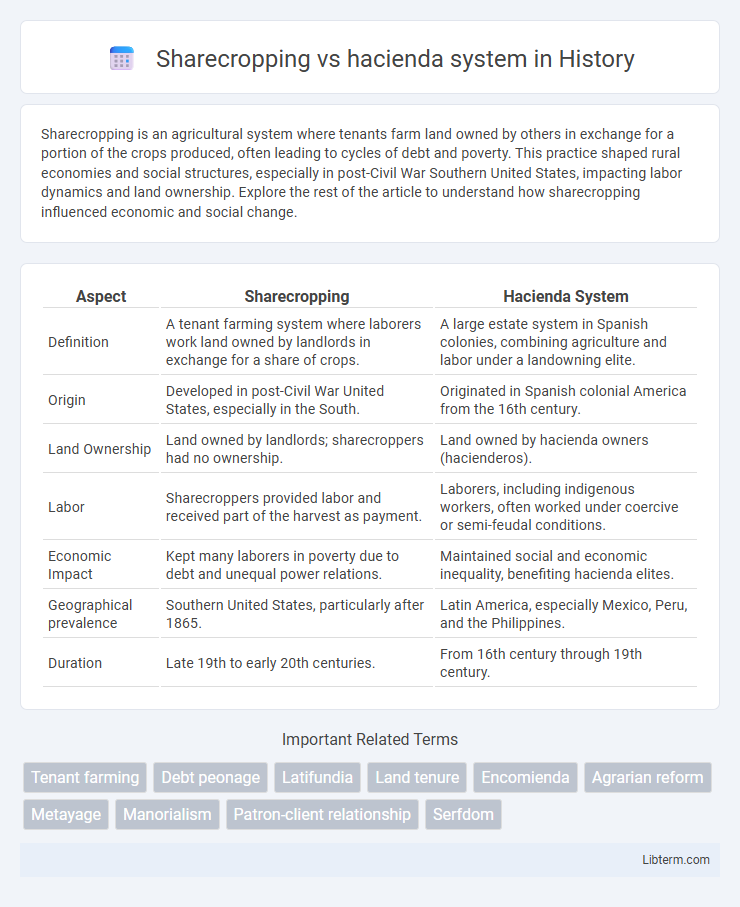

| Aspect | Sharecropping | Hacienda System |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A tenant farming system where laborers work land owned by landlords in exchange for a share of crops. | A large estate system in Spanish colonies, combining agriculture and labor under a landowning elite. |

| Origin | Developed in post-Civil War United States, especially in the South. | Originated in Spanish colonial America from the 16th century. |

| Land Ownership | Land owned by landlords; sharecroppers had no ownership. | Land owned by hacienda owners (hacienderos). |

| Labor | Sharecroppers provided labor and received part of the harvest as payment. | Laborers, including indigenous workers, often worked under coercive or semi-feudal conditions. |

| Economic Impact | Kept many laborers in poverty due to debt and unequal power relations. | Maintained social and economic inequality, benefiting hacienda elites. |

| Geographical prevalence | Southern United States, particularly after 1865. | Latin America, especially Mexico, Peru, and the Philippines. |

| Duration | Late 19th to early 20th centuries. | From 16th century through 19th century. |

Introduction to Sharecropping and Hacienda Systems

Sharecropping emerged as an agricultural system where tenant farmers cultivated land owned by landlords in exchange for a share of the crops produced, creating a cycle of debt and dependence. The hacienda system, prominent in Latin America, involved large estates owned by wealthy landowners who controlled both land and labor, often exploiting indigenous and local populations through forced labor or peonage. Both systems significantly shaped rural economies and social hierarchies by concentrating land ownership and limiting economic opportunities for peasants.

Historical Origins and Development

The sharecropping system emerged in the Southern United States after the Civil War as a way for landowners to maintain agricultural production without slave labor, relying on tenant farmers who gave a portion of their crops as rent. The hacienda system originated during Spanish colonial rule in Latin America, where large estates controlled by a landowning elite exploited indigenous labor under a feudal-like arrangement. Both systems developed as mechanisms of social and economic control, shaping rural labor relations and land tenure patterns in their respective regions.

Geographic Distribution and Prevalence

Sharecropping was predominantly widespread in the southern United States and parts of Latin America, where small-scale farmers cultivated rented plots and paid landlords with a portion of the crops. The hacienda system was mainly prevalent in Mexico, Peru, and other Andean regions, featuring large estates owned by wealthy landowners who controlled extensive agricultural and livestock operations. While sharecropping facilitated fragmented land use among tenant farmers, haciendas centralized land control under elite families, reflecting distinct social and economic structures across geographic regions.

Land Ownership and Control Structures

In the sharecropping system, land ownership remains with wealthy landlords while tenants cultivate the land in exchange for a portion of the crop yield, creating a dependent economic relationship with limited land control for farmers. The hacienda system features large estates owned by elite landowners who exert direct control over vast agricultural territories and laborers, often through hierarchical and coercive management structures. Both systems reinforce land concentration and social stratification, but sharecropping disperses cultivation among many tenants, whereas haciendas maintain centralized control over extensive landholdings.

Labor Relations and Social Hierarchies

Sharecropping established a tenant-laborer relationship where workers cultivated land in exchange for a share of the crop, often resulting in economic dependency and limited upward mobility for tenants. The hacienda system featured a rigid social hierarchy dominated by landowners who exercised significant control over indigenous and peasant laborers, reinforcing social stratification and labor exploitation. Both systems maintained unequal power dynamics but differed in structure, with sharecropping promoting contractual labor ties and haciendas sustaining feudal-like obligations.

Economic Incentives and Production Models

Sharecropping operated on a system where tenants cultivated land in exchange for a share of the crops, aligning economic incentives closely with individual labor and output, fostering a more flexible yet risky production model for both landowners and laborers. The hacienda system centralized production on large estates controlled by landlords who employed wage laborers or debt peons, emphasizing scale and hierarchical control with fixed economic returns for workers, often limiting incentives for increased productivity. While sharecropping incentivized tenant farmers to maximize yield due to profit-sharing, haciendas prioritized sustained output through labor management and resource control, shaping distinct agricultural production strategies.

Impact on Rural Communities

Sharecropping often led to cycles of debt and poverty for rural farmers, limiting economic mobility and reinforcing social inequalities. The hacienda system concentrated land ownership and wealth among large landowners, exacerbating disparities and reducing communal land access for Indigenous and peasant populations. Both systems contributed to entrenched rural poverty but differed in structure, with sharecropping creating dependency on landlords and haciendas maintaining hierarchical control over land and labor.

Transition and Decline of Both Systems

The transition from sharecropping to the hacienda system was marked by shifts in land ownership and labor dynamics, with sharecropping declining due to increased mechanization and land reforms promoting tenant rights. The hacienda system faced decline as political movements and agrarian laws redistributed large estates to peasant farmers, undermining the traditional landlord-tenant relationship. Both systems saw their economic viability diminish as national governments implemented policies favoring modernization and equitable land distribution.

Legacy and Influence on Modern Agriculture

The sharecropping system entrenched patterns of land dependency and limited economic mobility, influencing modern tenant farming practices and perpetuating rural poverty. The hacienda system's legacy includes large-scale landholdings and agrarian inequality, shaping contemporary land reform policies and agricultural labor dynamics in Latin America. Both systems contributed to social stratification and shaped the evolution of modern agricultural economies by reinforcing unequal land distribution and labor relations.

Comparative Analysis: Key Similarities and Differences

Sharecropping and the hacienda system both structured agrarian labor around landowners who controlled vast estates and peasants or tenants who worked the land, often facing economic dependency and limited mobility. Sharecropping typically involved tenant farmers giving a portion of their crop yield to landlords as rent, emphasizing individual cultivation plots, while the hacienda system centralized production on large estates with laborers working under more rigid hierarchical and often coercive conditions. Both systems perpetuated social inequality and restricted agrarian reform, but the hacienda system was more explicitly tied to colonial and postcolonial elite power structures, whereas sharecropping emerged as a post-slavery labor arrangement in various regions.

Sharecropping Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com