The Mughal Mansabdari System was a unique administrative framework that structured military and civil services through ranked positions called mansabs, determining the responsibilities and pay of officials based on their rank. This system ensured effective governance and military organization by linking rank to the number of troops an official had to maintain, thereby balancing power and loyalty within the empire. Explore the rest of the article to understand how this system shaped the Mughal administration and its lasting impact on Indian history.

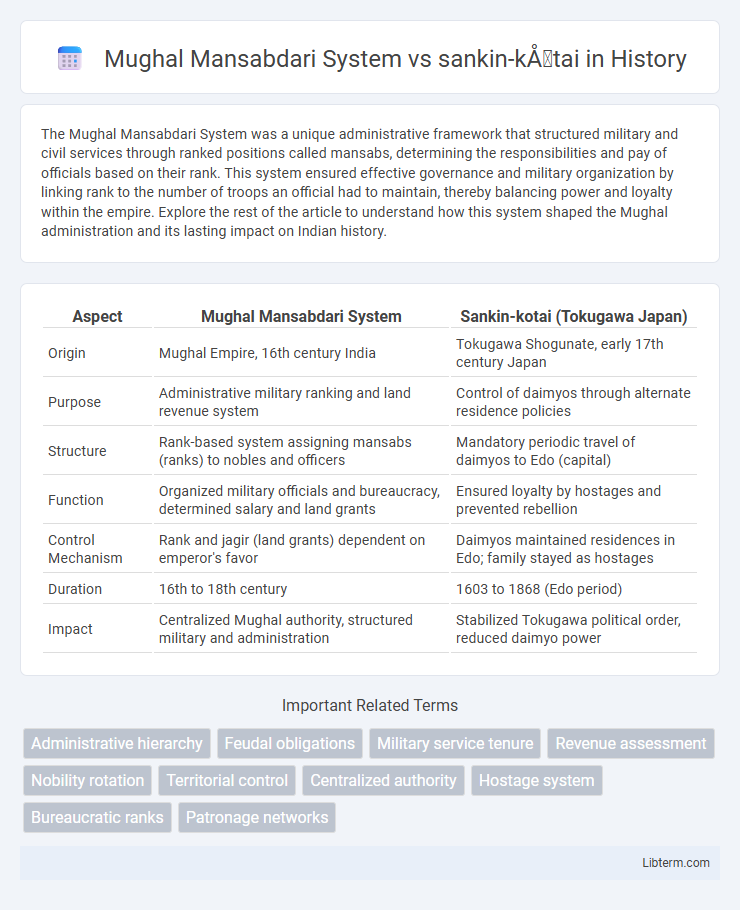

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Mughal Mansabdari System | Sankin-kotai (Tokugawa Japan) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Mughal Empire, 16th century India | Tokugawa Shogunate, early 17th century Japan |

| Purpose | Administrative military ranking and land revenue system | Control of daimyos through alternate residence policies |

| Structure | Rank-based system assigning mansabs (ranks) to nobles and officers | Mandatory periodic travel of daimyos to Edo (capital) |

| Function | Organized military officials and bureaucracy, determined salary and land grants | Ensured loyalty by hostages and prevented rebellion |

| Control Mechanism | Rank and jagir (land grants) dependent on emperor's favor | Daimyos maintained residences in Edo; family stayed as hostages |

| Duration | 16th to 18th century | 1603 to 1868 (Edo period) |

| Impact | Centralized Mughal authority, structured military and administration | Stabilized Tokugawa political order, reduced daimyo power |

Overview of the Mughal Mansabdari System

The Mughal Mansabdari System was a hierarchical administrative and military framework that assigned ranks (mansabs) to officials based on their role and loyalty, defining their salary and troops commanded. Mansabdars were responsible for maintaining a specified number of cavalrymen, ensuring centralized control and efficient governance across the empire. This system contrasted with Japan's Sankin-kotai, which mandated daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, functioning primarily as a political strategy to prevent rebellion rather than a military-administrative structure.

Introduction to Sankin-kōtai in Tokugawa Japan

The Sankin-kotai system in Tokugawa Japan mandated daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and the shogun's capital, Edo, to ensure loyalty and centralized control. This contrasts with the Mughal Mansabdari system, which assigned military and administrative ranks to nobles, integrating them into the imperial bureaucracy. Sankin-kotai emphasized physical presence and economic burden to curtail daimyo power, whereas Mansabdari focused on hierarchical rank and revenue assignment for governance.

Origins and Historical Context of Both Systems

The Mughal Mansabdari System, established by Emperor Akbar in the 16th century, functioned as a bureaucratic framework to rank military and civil officials based on their mansabs (ranks), ensuring centralized control over revenue and military obligations in the Indian subcontinent. In contrast, the Sankin-kotai system originated in the Edo period of Japan during the early 17th century under Tokugawa Ieyasu, mandating daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo to consolidate shogunal power and prevent rebellion. Both systems emerged from the need to stabilize and control vast territories through structured governance and loyalty enforcement, reflecting distinct cultural and political imperatives in Mughal India and Tokugawa Japan.

Structure and Hierarchy: Mansabdari vs Sankin-kōtai

The Mughal Mansabdari system featured a hierarchical administrative framework where mansabdars were ranked by numerical designations reflecting military and civil responsibilities, integrating both governance and military command within a central authority. In contrast, the Sankin-kotai system under the Tokugawa shogunate involved a strict feudal hierarchy where daimyo pledged loyalty by alternating residence between their domains and Edo, reinforcing central control through spatial obligations rather than integrated military rank. The Mansabdari system centralized power through rank-based appointments and jagir assignments, while Sankin-kotai maintained decentralization but ensured daimyo accountability via enforced attendance and residence patterns.

Recruitment and Appointment Processes

The Mughal Mansabdari system centralized recruitment by grading officials into hierarchical ranks called mansabs, which determined their military and civil duties based on merit and loyalty to the emperor. In contrast, the Japanese sankin-kotai system mandated daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, indirectly controlling appointments by requiring periodic attendance and allegiance to the shogun rather than direct recruitment. While Mansabdars were appointed through imperial decree and required to maintain troops proportional to their rank, sankin-kotai functioned as a strategic mechanism to ensure political stability through enforced mobility and hostageship rather than formal positions of rank.

Role in Central and Regional Administration

The Mughal Mansabdari System centralized authority by assigning military and administrative ranks to officials who directly reported to the emperor, ensuring efficient governance and troop mobilization across the empire. In contrast, Japan's Sankin-kotai system decentralized power by mandating daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, facilitating shogunal control while allowing regional autonomy. Both systems maintained hierarchical control but differed in their approach to balancing central authority with regional administration.

Economic Implications and Revenue Systems

The Mughal Mansabdari System centralized revenue collection by assigning military and administrative ranks (mansabs) linked to jagir land grants, ensuring efficient tax collection and maintaining imperial control over provincial economies. In contrast, the Japanese Sankin-kotai system imposed periodic residence requirements on daimyos, compelling them to spend alternate years in Edo, which drained their financial resources through costly travel and mansion maintenance, indirectly strengthening the shogunate's fiscal dominance. Both systems sustained state revenue but differed: Mansabdari integrated military obligations with land revenue administration, while Sankin-kotai leveraged social control mechanisms to limit daimyo wealth accumulation and reinforce centralized authority.

Social Impact and Control Mechanisms

The Mughal Mansabdari system created a hierarchical bureaucracy where mansabdars were granted ranks and land revenue rights to maintain military and administrative control, facilitating centralized governance and social order through patronage and loyalty. Sankin-kotai, practiced in feudal Japan, mandated daimyo to alternate residency between their domains and Edo, ensuring political control by imposing financial burdens and hostage-like residency, which limited regional autonomy and reinforced the shogunate's authority. Both systems effectively balanced social control and political stability, with Mansabdari emphasizing military service and land revenue management, while Sankin-kotai leveraged enforced mobility and economic strain to prevent rebellion.

Decline and Reforms: Transition in Both Systems

The Mughal Mansabdari System declined due to administrative corruption, military inefficiency, and the increasing autonomy of jagirdars, prompting reforms that aimed to centralize authority and curb malpractices. Sankin-kotai in feudal Japan weakened as Tokugawa shogunate's control diminished, facing rising financial burdens and samurai discontent, leading to the system's eventual abolition during the Meiji Restoration reforms. Both transitions reflect shifts from decentralized feudal control toward centralized modern governance structures driven by political and economic pressures.

Comparative Analysis: Lasting Legacies and Influence

The Mughal Mansabdari system established a hierarchical military-administrative framework that centralized authority by ranking nobles based on their mansabs, ensuring loyalty through land revenue assignments, which influenced later Indian governance structures. In contrast, Japan's sankin-kotai mandated daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, effectively controlling regional powers and fostering economic development through mandatory attendance. Both systems engineered centralized control and political stability, but the Mansabdari system's impact shaped imperial administration and land revenue practices, while sankin-kotai's legacy contributed to Japan's urban growth and the Tokugawa shogunate's enduring political cohesion.

Mughal Mansabdari System Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com