Febronianism challenges the centralized authority of the papacy by advocating for increased power and autonomy of local bishops within the Catholic Church. It promotes a more decentralized church governance structure, emphasizing the role of national churches and conciliarism. Discover how Febronianism reshaped church politics and the broader impact it had on ecclesiastical history in the full article.

Table of Comparison

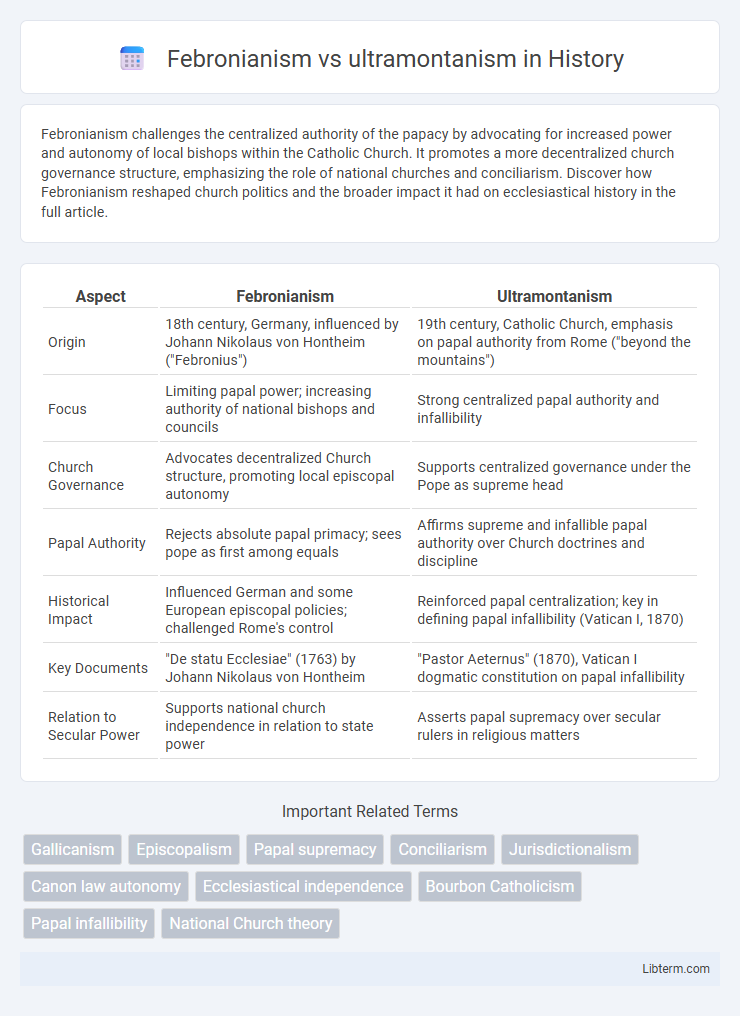

| Aspect | Febronianism | Ultramontanism |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | 18th century, Germany, influenced by Johann Nikolaus von Hontheim ("Febronius") | 19th century, Catholic Church, emphasis on papal authority from Rome ("beyond the mountains") |

| Focus | Limiting papal power; increasing authority of national bishops and councils | Strong centralized papal authority and infallibility |

| Church Governance | Advocates decentralized Church structure, promoting local episcopal autonomy | Supports centralized governance under the Pope as supreme head |

| Papal Authority | Rejects absolute papal primacy; sees pope as first among equals | Affirms supreme and infallible papal authority over Church doctrines and discipline |

| Historical Impact | Influenced German and some European episcopal policies; challenged Rome's control | Reinforced papal centralization; key in defining papal infallibility (Vatican I, 1870) |

| Key Documents | "De statu Ecclesiae" (1763) by Johann Nikolaus von Hontheim | "Pastor Aeternus" (1870), Vatican I dogmatic constitution on papal infallibility |

| Relation to Secular Power | Supports national church independence in relation to state power | Asserts papal supremacy over secular rulers in religious matters |

Introduction to Febronianism and Ultramontanism

Febronianism emerged in the 18th century as a movement advocating for the reduction of papal authority in favor of greater national church autonomy, emphasizing the role of bishops and secular rulers in church governance. Ultramontanism, in contrast, championed strong papal supremacy and centralized authority in Rome, asserting the Pope's ultimate jurisdiction over both spiritual and temporal matters within the Catholic Church. These opposing theological and political doctrines shaped conflicts between centralized papal control and decentralized ecclesiastical independence during the period.

Historical Origins and Development

Febronianism emerged in the 18th century as a movement advocating for the reduction of papal authority and increased power for national churches, rooted in the writings of Johann Nikolaus von Hontheim under the pseudonym "Febronius." Ultramontanism developed as a counter-movement emphasizing strong papal supremacy and centralization of ecclesiastical power in Rome, gaining momentum especially after the First Vatican Council in 1870 with the formal declaration of papal infallibility. These opposing doctrines shaped the political and religious conflicts between national churches and the papacy in Europe during the Enlightenment and Modern periods.

Core Doctrines and Beliefs

Febronianism advocates for reducing papal authority and increasing the power of national bishops and councils, emphasizing the autonomy of local churches within the Catholic tradition. Ultramontanism supports strong papal supremacy, asserting the pope's ultimate authority over all ecclesiastical matters to maintain church unity and doctrinal consistency. These opposing doctrines highlight the tension between centralized papal control and decentralized episcopal governance in the Catholic Church.

Key Figures and Influencers

Febronianism, championed by Johann Nikolaus von Hontheim under the pseudonym Febronius, advocated limiting papal authority in favor of greater episcopal autonomy within the Catholic Church. Key ultramontanist figures include Pope Pius IX and Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, who defended strong papal supremacy and centralized ecclesiastical governance. The ideological conflict shaped 18th and 19th-century Church politics, influencing debates on authority between national churches and the Vatican.

Authority of the Pope: Central Issue

Febronianism challenges papal authority by advocating for the limitation of the Pope's power and promoting the autonomy of national churches and bishops, emphasizing a conciliar model of governance. Ultramontanism asserts the supreme authority of the Pope over the entire Catholic Church, supporting centralized papal control and infallibility, especially in matters of doctrine. The central issue between these positions hinges on whether ultimate ecclesiastical authority resides with the Pope alone or is distributed among bishops and local church structures.

National Churches vs. Universal Papacy

Febronianism advocates for the autonomy of national churches, emphasizing local episcopal authority and reducing papal influence to promote regional religious governance within Catholicism. Ultramontanism upholds the supremacy of the universal papacy, asserting the pope's ultimate authority over all churches, reinforcing centralized ecclesiastical power. This ideological conflict shapes the balance between national ecclesiastical independence and the cohesive governance of the Roman Catholic Church.

Major Events and Debates

The Febronianism movement, rooted in the 1763 work "De Statu Ecclesiae," catalyzed major debates by advocating for the limitation of papal authority and increased power for national bishops, sparking conflict during the Enlightenment. The 18th-century Council of Pistoia (1786) epitomized Febronian efforts to reform Church hierarchy, but faced condemnation from Pope Pius VI in the bull "Auctorem Fidei" (1794), reinforcing ultramontanist centralization. The 19th-century First Vatican Council (1869-1870) marked a decisive ultramontanist victory, dogmatically defining papal infallibility and marginalizing Febronian ideals of decentralized ecclesiastical governance.

Impact on Church-State Relations

Febronianism advocated for limiting papal authority and increased autonomy of national churches, thereby fostering stronger state control over ecclesiastical matters and promoting the subordination of Church to secular rulers. Ultramontanism emphasized the centralization of papal power and the Pope's supreme authority, reinforcing the Church's independence from state interference and advocating for a unified, transnational Catholic hierarchy. The clash between these ideologies significantly shaped Church-State relations, influencing legal frameworks and political dynamics across Catholic Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Lasting Influence on Modern Catholicism

Febronianism challenged papal absolutism by advocating for increased authority of national bishops, influencing the development of conciliarism and shaping debates on church-state relations within modern Catholicism. Ultramontanism reinforced papal supremacy and centralized ecclesiastical authority, culminating in the doctrine of papal infallibility defined at the First Vatican Council in 1870, which remains a cornerstone of contemporary Catholic ecclesiology. The tension between these movements persists in discussions on decentralization versus centralized authority, impacting modern theological and administrative practices in the Catholic Church.

Conclusion: Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Febronianism, emphasizing national church authority and limiting papal power, significantly influenced 18th-century Catholic thought and contributed to modern debates on church governance and local episcopal autonomy. Ultramontanism, advocating strong papal supremacy and centralized ecclesiastical authority, shaped the doctrinal development of the First Vatican Council (1870) and remains foundational for the contemporary Catholic Church's hierarchical structure. The ongoing tension between these positions reflects enduring challenges in balancing universal papal authority with national and regional ecclesiastical independence.

Febronianism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com