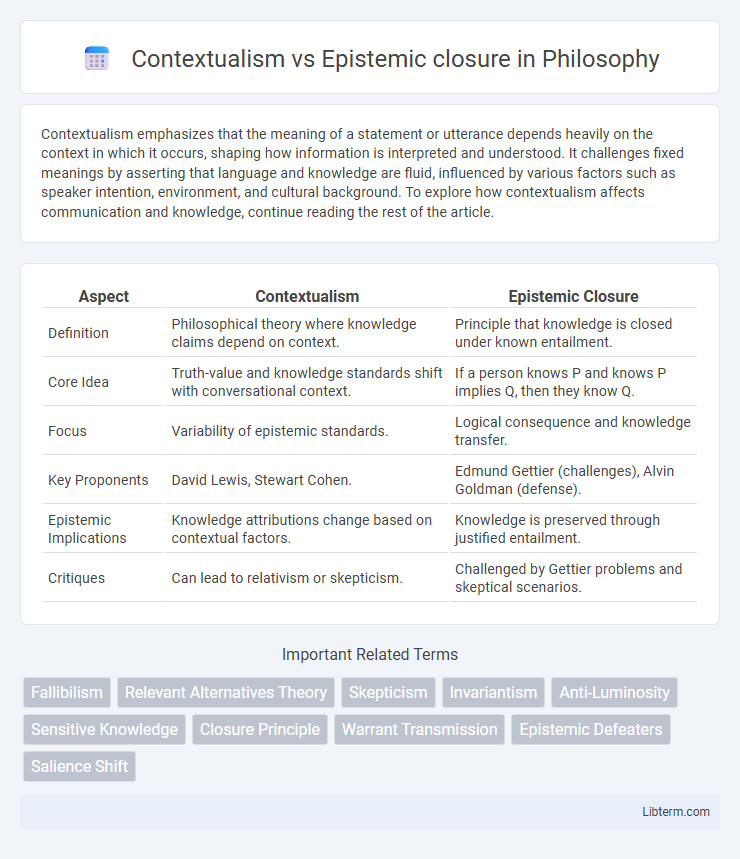

Contextualism emphasizes that the meaning of a statement or utterance depends heavily on the context in which it occurs, shaping how information is interpreted and understood. It challenges fixed meanings by asserting that language and knowledge are fluid, influenced by various factors such as speaker intention, environment, and cultural background. To explore how contextualism affects communication and knowledge, continue reading the rest of the article.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Contextualism | Epistemic Closure |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Philosophical theory where knowledge claims depend on context. | Principle that knowledge is closed under known entailment. |

| Core Idea | Truth-value and knowledge standards shift with conversational context. | If a person knows P and knows P implies Q, then they know Q. |

| Focus | Variability of epistemic standards. | Logical consequence and knowledge transfer. |

| Key Proponents | David Lewis, Stewart Cohen. | Edmund Gettier (challenges), Alvin Goldman (defense). |

| Epistemic Implications | Knowledge attributions change based on contextual factors. | Knowledge is preserved through justified entailment. |

| Critiques | Can lead to relativism or skepticism. | Challenged by Gettier problems and skeptical scenarios. |

Introduction to Contextualism and Epistemic Closure

Contextualism in epistemology asserts that the truth-value of knowledge claims depends on the context, meaning that what counts as "knowing" can shift based on relevant standards in different situations. Epistemic closure is the principle that if a person knows a proposition and also knows that this proposition implies a second one, then they must also know the second proposition. The debate between contextualism and epistemic closure centers on whether knowledge is preserved across known implications or varies with contextual factors influencing knowledge attributions.

Defining Contextualism in Epistemology

Contextualism in epistemology asserts that the truth conditions of knowledge attributions vary depending on the speaker's context, thereby influencing the standards for what counts as "knowing." This view contrasts with epistemic closure, which holds that knowledge is closed under known logical implication, meaning if a subject knows P and knows that P implies Q, then the subject also knows Q. Contextualism challenges epistemic closure by allowing knowledge attributions to shift with contextual factors, suggesting that a person might know P without necessarily knowing Q in a different context due to changing standards of knowledge justification.

The Principle of Epistemic Closure Explained

The Principle of Epistemic Closure asserts that if a subject knows a proposition p and also knows that p entails another proposition q, then the subject must know q. Contextualism challenges this principle by arguing that the standards for "knowing" vary depending on the context, affecting whether epistemic closure holds in different situations. This debate centers on whether knowledge is invariant or context-sensitive, impacting how epistemic closure is applied in epistemology.

Historical Background and Philosophical Origins

Contextualism in epistemology emerged in the late 20th century, inspired by pragmatic theories of language by philosophers like David Kaplan and Stewart Cohen, emphasizing how knowledge claims vary based on conversational context. Epistemic closure, a principle rooted in classical epistemology dating back to the works of philosophers such as Edmund Gettier and Laurence BonJour, asserts that knowledge is closed under known entailment, meaning if one knows a proposition and knows it entails another, one also knows that other proposition. The historical tension between contextualism and epistemic closure stems from their differing responses to skepticism, with contextualists denying closure in shifting contexts while traditional epistemologists uphold closure as a cornerstone of knowledge.

Key Arguments for Contextualism

Contextualism argues that the truth conditions of knowledge attributions vary depending on the context, allowing for shifts in the standards of "knowing" based on factors like practical stakes or conversational context. This approach addresses skepticism by explaining how knowledge claims can be true in everyday contexts yet fail under stringent skeptical scenarios, avoiding the need to reject commonsense knowledge. Contextualists emphasize the importance of pragmatic factors and the dynamic nature of epistemic standards, challenging the rigid framework of epistemic closure which holds that knowledge is always closed under known entailment.

Major Defenses of Epistemic Closure

Epistemic closure asserts that if a subject knows a proposition P and knows that P implies Q, then the subject also knows Q, serving as a cornerstone in traditional epistemology. Major defenses of epistemic closure appeal to the preservation of knowledge through logical entailment, emphasizing its role in maintaining coherent and stable knowledge systems. Critics such as contextualists argue that knowledge attributions vary with context, but defenders maintain closure to protect against skepticism and uphold epistemic principles like deductive closure and the transparency of knowledge.

Contextualism’s Challenge to Closure Principles

Contextualism challenges epistemic closure principles by arguing that the standards for knowledge attribution vary based on context, which means knowledge claims can shift depending on conversational factors and practical stakes. This variability undermines the closure principle that if a subject knows proposition P and knows that P entails Q, then the subject must also know Q. Contextualism thereby provides a flexible framework that resists the rigid application of closure, emphasizing how knowledge attributions are sensitive to context rather than fixed logical relations.

Notable Thought Experiments and Case Studies

The debate between contextualism and epistemic closure is highlighted by notable thought experiments such as the "Bank Case" and the "Barn County" scenario, which challenge the infallibility of knowledge attributions across different contexts. These case studies illustrate how contextualists argue that standards for knowledge vary with conversational context, while proponents of epistemic closure defend the principle that knowledge is closed under known logical implications. Experimental philosophy approaches and real-world applications in legal and scientific reasoning continue to test these theories, revealing the nuanced interplay between context sensitivity and closure in epistemic practices.

Criticisms and Counterarguments

Criticisms of Contextualism often highlight its perceived instability in knowledge ascriptions, arguing that shifting standards based on conversational context undermine objective epistemic evaluation. Counterarguments emphasize that Contextualism accounts for the pragmatic nuances of language, preserving intuitive judgments about knowledge in everyday discourse. On the other hand, challenges to Epistemic Closure focus on its rigid logical framework, which struggles to accommodate scenarios involving skeptical hypotheses, prompting defenders to refine the principle or propose alternative formulations to maintain coherence in epistemic reasoning.

Implications for Knowledge and Skepticism

Contextualism challenges epistemic closure by asserting that the truth conditions of knowledge claims vary with context, affecting how knowledge is attributed in skeptical scenarios. This view implies that knowledge is sensitive to practical stakes and conversational contexts, undermining skepticism by limiting the applicability of closure principles. In contrast, epistemic closure upholds that knowledge is closed under known entailment, reinforcing skepticism by suggesting that if one knows a proposition, one must also know all its logical consequences, including skeptical hypotheses.

Contextualism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com