Synthetic materials are engineered through chemical processes to mimic natural substances while offering enhanced durability, flexibility, and resistance to environmental factors. These materials find applications in industries ranging from fashion and automotive to healthcare and technology, providing innovative solutions for modern challenges. Explore the rest of the article to discover how synthetic materials can transform your projects and everyday life.

Table of Comparison

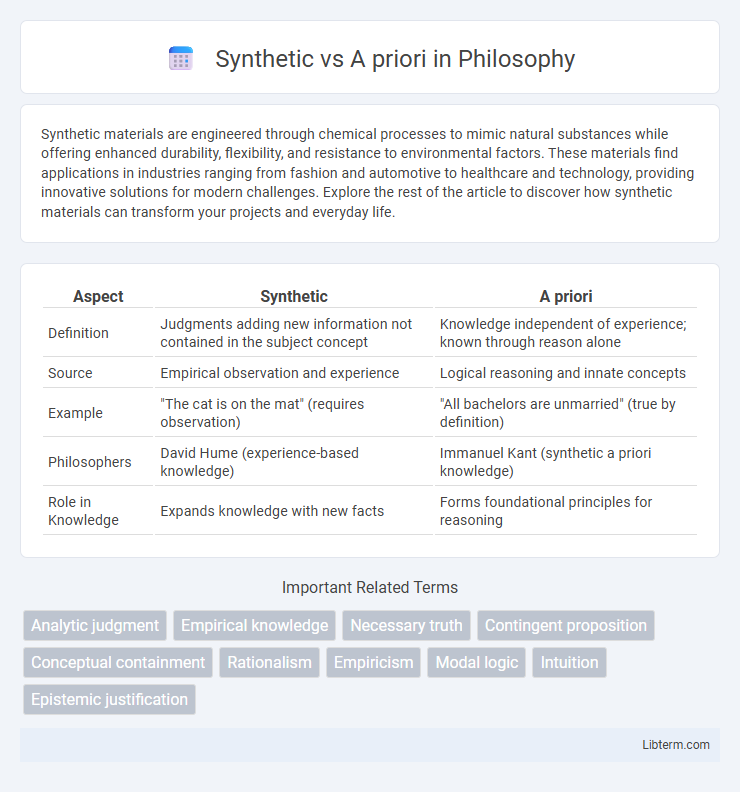

| Aspect | Synthetic | A priori |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Judgments adding new information not contained in the subject concept | Knowledge independent of experience; known through reason alone |

| Source | Empirical observation and experience | Logical reasoning and innate concepts |

| Example | "The cat is on the mat" (requires observation) | "All bachelors are unmarried" (true by definition) |

| Philosophers | David Hume (experience-based knowledge) | Immanuel Kant (synthetic a priori knowledge) |

| Role in Knowledge | Expands knowledge with new facts | Forms foundational principles for reasoning |

Understanding Synthetic and A Priori Concepts

Synthetic concepts expand knowledge by connecting predicates to subjects in ways not contained within the concept's definition, relying on empirical evidence or experience. A priori concepts, however, are known independently of experience, providing foundational knowledge that is universally true and necessary, such as mathematical truths. Understanding these distinctions clarifies how knowledge can be both derived from experience and established through inherent reasoning.

Historical Background: Kant and the Philosophical Debate

Immanuel Kant revolutionized philosophy by distinguishing between synthetic and a priori judgments, challenging the prevailing rationalist-empiricist debate of the 18th century. His critical philosophy asserted that synthetic a priori knowledge is possible, meaning some knowledge is both informative and known independently of experience. This groundbreaking idea reshaped epistemology and laid the foundation for modern discussions on the nature of knowledge and human understanding.

Defining Synthetic Judgments

Synthetic judgments expand knowledge by connecting concepts whose relationship is not inherently contained within the subject, making their truth dependent on empirical verification or external information. A priori knowledge is independent of experience, providing necessary and universal truths, whereas synthetic judgments often require empirical input to validate propositions about the world. The distinction emphasizes how synthetic judgments extend understanding beyond mere definitional analysis by incorporating new, substantive content.

Defining A Priori Knowledge

A priori knowledge refers to information or understanding that is independent of sensory experience and can be known through reason alone, such as mathematical truths or logical deductions. This type of knowledge is contrasted with synthetic knowledge, which depends on empirical evidence and observation for validation. Defining a priori knowledge emphasizes its role as inherently necessary and universally applicable without needing empirical verification.

Key Differences Between Synthetic and A Priori

Synthetic judgments expand knowledge by connecting concepts beyond their definitions, whereas a priori judgments are known independently of experience and rely on pure reason. Synthetic propositions require empirical evidence to determine their truth, while a priori propositions are necessarily true and derived through logical deduction. The key difference lies in how knowledge is obtained: synthetic knowledge depends on sensory experience, whereas a priori knowledge is innate or self-evident.

The Synthetic A Priori: Bridging the Gap

The synthetic a priori knowledge bridges empirical observation and rational insight by combining elements of both synthetic and a priori judgments. This concept, prominently advanced by Immanuel Kant, asserts that certain universal truths are known independently of experience yet provide substantive information about the world. Examples include fundamental principles of mathematics and causality, which ground scientific inquiry through necessary and informative propositions.

Real-World Examples: Applications in Science and Mathematics

Synthetic judgments, as exemplified in physics, derive new knowledge through empirical observation and experimentation, such as determining the mass of an object or measuring gravitational forces. A priori principles, foundational in mathematics, include tautologies like 2+2=4 and geometric axioms, which are knowable independently of experience and underpin logical reasoning and proofs. Real-world applications reflect the interplay between these, where synthetic data informs scientific models, while a priori assumptions structure mathematical frameworks essential for technology and engineering solutions.

Critiques and Controversies

Synthetic judgments, often criticized for their reliance on empirical observation, face scrutiny regarding their claim to provide necessary knowledge, which some philosophers argue limits their epistemic certainty compared to a priori judgments. A priori knowledge is contested for potentially assuming innate concepts without sufficient empirical grounding, raising debates about its universal validity and cognitive accessibility. The controversy centers on whether synthetic a priori knowledge truly exists or if all knowledge is either purely empirical or analytic, challenging Kantian epistemology and prompting ongoing philosophical discourse.

Modern Perspectives and Interpretations

Modern perspectives on synthetic versus a priori knowledge emphasize the evolving understanding of how empirical data interacts with innate cognitive frameworks, challenging traditional Kantian distinctions. Contemporary philosophers and cognitive scientists explore the dynamic interplay between a priori concepts and synthetic judgments to explain knowledge formation more fluidly. Advances in epistemology highlight that synthetic a priori judgments may stem from cognitive structures shaped by both innate faculties and experiential input, reflecting a nuanced synthesis rather than a strict dichotomy.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Relevance of Synthetic vs. A Priori

The distinction between synthetic and a priori knowledge remains a foundational debate in epistemology, influencing contemporary discussions on how we acquire and justify knowledge. Synthetic judgments expand our understanding by connecting concepts in ways not contained within their definitions, while a priori knowledge provides necessary truths independent of experience. This ongoing relevance shapes fields like philosophy, cognitive science, and artificial intelligence by informing theories of knowledge acquisition and reasoning processes.

Synthetic Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com