Disjunctivism challenges traditional views on perception by arguing that veridical perceptions and hallucinations are fundamentally different in nature rather than similar mental states. This theory emphasizes the direct connection between the perceiver and the external world in genuine experiences, rejecting the idea that both perception and illusion share the same underlying processes. Explore the rest of the article to understand how disjunctivism reshapes debates in philosophy of mind and epistemology.

Table of Comparison

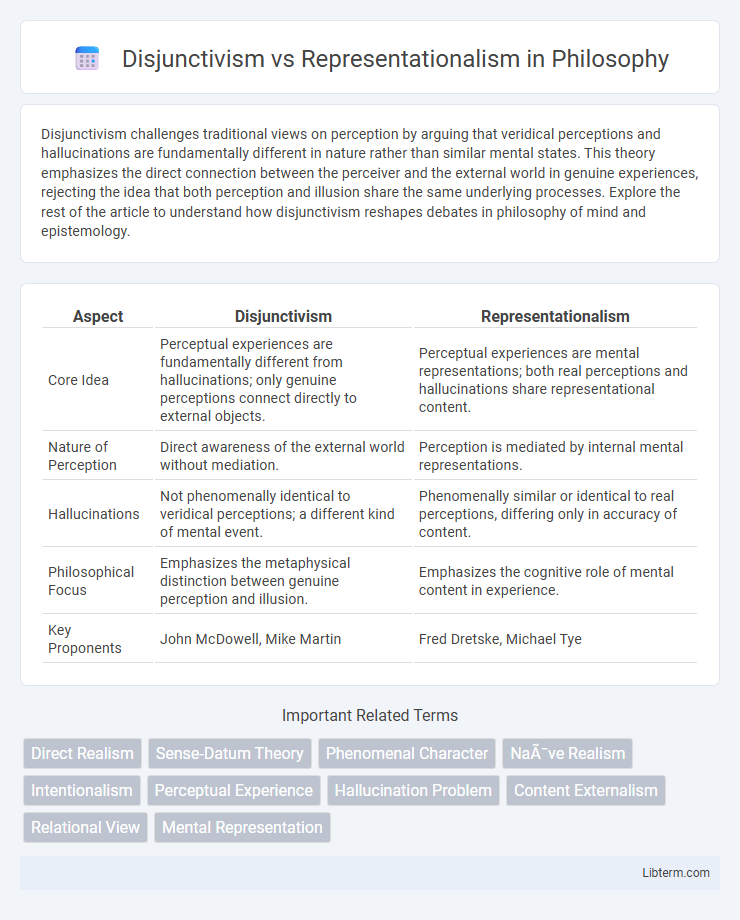

| Aspect | Disjunctivism | Representationalism |

|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Perceptual experiences are fundamentally different from hallucinations; only genuine perceptions connect directly to external objects. | Perceptual experiences are mental representations; both real perceptions and hallucinations share representational content. |

| Nature of Perception | Direct awareness of the external world without mediation. | Perception is mediated by internal mental representations. |

| Hallucinations | Not phenomenally identical to veridical perceptions; a different kind of mental event. | Phenomenally similar or identical to real perceptions, differing only in accuracy of content. |

| Philosophical Focus | Emphasizes the metaphysical distinction between genuine perception and illusion. | Emphasizes the cognitive role of mental content in experience. |

| Key Proponents | John McDowell, Mike Martin | Fred Dretske, Michael Tye |

Introduction to Disjunctivism and Representationalism

Disjunctivism argues that veridical perceptions and hallucinations are fundamentally different in nature, rejecting the idea that both share a common representational content. Representationalism holds that both veridical experiences and hallucinations involve mental representations that can be indistinguishable in their content. This contrast centers on whether perceptual experiences are to be understood as relational states directly connected to the world or as internal representations that may or may not correspond to external objects.

Historical Background and Philosophical Roots

Disjunctivism originated in the late 20th century as a challenge to traditional epistemology, particularly critiquing representationalism's reliance on mental representations to explain perceptual experience. Rooted in the works of philosophers like G.E. Moore and Ludwig Wittgenstein, disjunctivism emphasizes a direct realist approach, arguing that veridical perception and hallucination are fundamentally different in nature. Representationalism, tracing its philosophical roots to John Locke and further developed by contemporary analytic philosophers, asserts that perceptual experiences are mediated by internal representations that correspond to external reality.

Core Principles of Disjunctivism

Disjunctivism asserts that veridical perceptions and hallucinations are fundamentally different in nature, emphasizing the directness of perception in genuine cases. It holds that perceptual experiences either directly present actual objects or are merely misleading without sharing a common experiential core. This contrasts with Representationalism, which posits that all experiences, including hallucinations, share the same representational content regardless of their truth.

Key Tenets of Representationalism

Representationalism posits that perceptual experiences are fundamentally mental representations that accurately or inaccurately depict the external world, emphasizing the mind's capacity to generate content independent of direct causal contact with objects. Key tenets include the internalist view that the phenomenal character of experience is determined by representational content, and that misperceptions like illusions or hallucinations share similar representational structures with veridical perceptions. This theory contrasts with Disjunctivism by rejecting a strict dichotomy between veridical perception and hallucination, instead proposing a unified explanatory framework based on representational content.

Perceptual Experience: Comparing Both Theories

Disjunctivism asserts that veridical perceptions and hallucinations are fundamentally different in nature, emphasizing that genuine perceptual experiences directly relate to the external world. Representationalism, on the other hand, holds that all perceptual experiences, including illusions and hallucinations, share a common representational content regardless of their external cause. Both theories aim to explain how perception conveys information, but Disjunctivism prioritizes the realist connection to objects, whereas Representationalism focuses on the internal representational structure of experience.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Disjunctivism

Disjunctivism's strength lies in its ability to distinguish between veridical perceptions and hallucinations, maintaining that direct awareness in genuine perception provides immediate access to the external world, thus preserving epistemic certainty. A key weakness is its difficulty in explaining the phenomenological similarity between hallucinations and veridical experiences, leading to challenges in accounting for subjective experience uniformly. Moreover, disjunctivism faces criticism for its potentially high ontological commitments by positing fundamentally different kinds of mental states in perception versus hallucination.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Representationalism

Representationalism excels in explaining perceptual experience by positing that mental representations directly correspond to external reality, providing a clear framework for understanding how we perceive the world. However, it struggles with the problem of misrepresentation, as it cannot fully account for illusions or hallucinations where the mental representation diverges from actual objects. This limitation challenges its ability to explain subjective perceptual errors, highlighting a significant weakness compared to Disjunctivism, which treats veridical perception and hallucination as fundamentally different kinds of experiences.

Major Figures and Influential Works

Disjunctivism, prominently advocated by philosophers like John McDowell and Mike Martin, challenges the traditional Representationalist view by insisting that veridical perceptions and hallucinations are fundamentally different in nature, as detailed in McDowell's "The Engaged Observer" and Martin's "The Reality of Appearances." Representationalism, championed by Fred Dretske and Michael Tye, posits that all perceptual experiences are representational states, with key contributions found in Dretske's "Knowledge and the Flow of Information" and Tye's "The Imagery Debate." These major figures and works shape ongoing debates in philosophy of mind, focusing on how perception relates to reality and consciousness.

Ongoing Debates and Contemporary Developments

Disjunctivism challenges Representationalism by asserting that veridical perceptual experiences fundamentally differ from hallucinations at the level of phenomenal character, fueling ongoing debates over the nature of perceptual content and consciousness. Recent developments explore neurophenomenological evidence and Bayesian models to substantiate Disjunctivist claims, prompting reevaluations of cognitive architecture and intentionality. Contemporary discourse centers on reconciling empirical findings with metaphysical commitments, fostering interdisciplinary approaches in philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

Conclusion: Implications for the Philosophy of Perception

Disjunctivism challenges representationalism by asserting that veridical perceptions and hallucinations differ fundamentally in nature, influencing debates on the directness of perceptual experience. This distinction impacts the philosophy of perception by questioning whether perceptual experience must always involve representational content or if it can sometimes be a direct relational state with the world. The implications underscore the need for revised theories that accommodate the diversity of perceptual phenomena while addressing the epistemological concerns of how perception justifies beliefs about reality.

Disjunctivism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com