Contingency refers to the planning and preparation for unexpected events that may disrupt normal operations or goals. Effective contingency strategies help mitigate risks and ensure resilience in various situations. Discover how your organization can develop robust contingency plans by reading the full article.

Table of Comparison

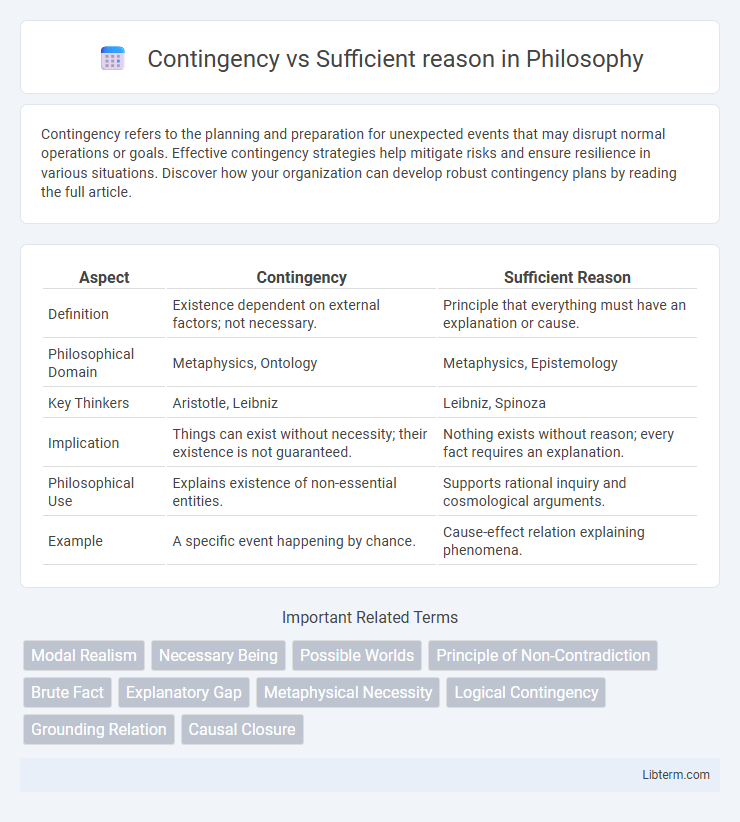

| Aspect | Contingency | Sufficient Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Existence dependent on external factors; not necessary. | Principle that everything must have an explanation or cause. |

| Philosophical Domain | Metaphysics, Ontology | Metaphysics, Epistemology |

| Key Thinkers | Aristotle, Leibniz | Leibniz, Spinoza |

| Implication | Things can exist without necessity; their existence is not guaranteed. | Nothing exists without reason; every fact requires an explanation. |

| Philosophical Use | Explains existence of non-essential entities. | Supports rational inquiry and cosmological arguments. |

| Example | A specific event happening by chance. | Cause-effect relation explaining phenomena. |

Introduction to Contingency and Sufficient Reason

Contingency refers to events or facts that could be otherwise, dependent on external conditions and not necessarily true in all possible worlds. Sufficient reason is a philosophical principle stating that everything must have a reason or cause that explains why it is the way it is rather than otherwise. Understanding the distinction between contingency and sufficient reason is essential in metaphysics and logic to analyze causality and existence.

Defining Contingent Facts

Contingent facts are conditions or events that may or may not occur, depending on circumstances and are not necessarily true in all possible worlds. They contrast with necessary facts, which must be true under all conditions. Understanding contingent facts is essential in distinguishing them from facts supported by sufficient reason, where sufficient reason implies a justification or explanation that inevitably leads to a specific outcome.

Understanding the Principle of Sufficient Reason

The Principle of Sufficient Reason asserts that everything must have a reason or cause, contrasting with the concept of contingency, where events or entities exist without a necessary cause. This principle underpins philosophical arguments in metaphysics, emphasizing that nothing is without explanation or justification. Understanding this principle aids in distinguishing between contingent phenomena, which depend on external causes, and necessary truths grounded in sufficient reasons.

Historical Background and Philosophical Origins

The concepts of contingency and sufficient reason trace back to ancient Greek philosophy, with Aristotle introducing the principle of sufficient reason as a foundational metaphysical tenet explaining why things exist or happen. Leibniz later formalized the principle of sufficient reason, asserting that nothing occurs without a reason, thereby contrasting with contingency, which denotes events or states that could be otherwise without a definitive cause. These ideas shaped classical metaphysics and influenced the development of modern philosophical inquiries into causality and existence.

Key Differences Between Contingency and Sufficient Reason

Contingency refers to events or facts that could be otherwise, relying on external conditions for their existence, whereas sufficient reason involves an explanation or cause that guarantees the truth or occurrence of a phenomenon. The key difference lies in contingency's openness to alternative possibilities contrasted with sufficient reason's role as a definitive causal or explanatory principle ensuring necessity. Conceptually, contingency emphasizes variability and dependence on external factors, while sufficient reason anchors explanations in definitive justification or cause.

Famous Philosophers on Contingency vs Sufficient Reason

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz famously articulated the Principle of Sufficient Reason, asserting that for everything that exists, there must be a reason explaining why it is so rather than otherwise. Baruch Spinoza, in contrast, emphasized a deterministic view where contingency is an illusion, and all things follow from the necessity of the divine nature. David Hume challenged both positions by highlighting the limits of human reason in discovering necessary connections, thus underscoring the role of contingency in empirical experience.

Applications in Metaphysics and Epistemology

Contingency refers to events or propositions that could be otherwise, lacking necessity, which is pivotal in metaphysical discussions about the existence and nature of reality, particularly in debates on the existence of God and the universe's dependence. The Principle of Sufficient Reason posits that everything must have a reason or cause, serving as a foundational concept in both metaphysics and epistemology to justify beliefs and explain phenomena. These concepts are applied to analyze causality, existence, and knowledge justification, influencing arguments for necessary beings and the rational structure of the world.

Criticisms and Counterarguments

Criticisms of the Contingency argument highlight its reliance on the principle of sufficient reason, which some argue lacks empirical support and may lead to infinite regress. Counterarguments emphasize that the concept of a necessary being as a sufficient reason remains philosophically robust, addressing concerns about the completeness and explanatory power of the argument. The debate continues over whether the principle of sufficient reason is a valid metaphysical foundation for proving existence beyond contingency.

Contingency, Sufficient Reason, and Modern Science

Contingency refers to events or facts that could be otherwise and depend on external conditions, contrasting with the principle of Sufficient Reason, which asserts that everything must have a reason or cause explaining why it is the case. Modern science often operates under the framework of sufficient reason by seeking reproducible causes and explanations for phenomena, yet it also encounters contingent realities in quantum mechanics and emergent systems where outcomes appear probabilistic or context-dependent. The interplay between contingency and sufficient reason in scientific inquiry challenges deterministic views and encourages deeper exploration of causality and explanation.

Summary and Implications for Philosophy

Contingency refers to events or states that could be otherwise, lacking necessity, while sufficient reason denotes the principle that everything must have a definitive explanation or cause. The philosophical debate centers on whether the universe and existence itself are contingent, requiring external reasons, or if sufficient reasons inherently justify all phenomena. This distinction shapes metaphysical discussions about causality, the nature of existence, and the limits of human understanding in explaining reality.

Contingency Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com