Receptionism emphasizes the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist through the faithful's reception and faith, believing that the sacrament's grace is effective only when received worthily. This theological view contrasts with transubstantiation by focusing on the believer's acceptance rather than a metaphysical change in the elements. Explore the rest of this article to understand how Receptionism shapes your approach to communion and its significance in Christian worship.

Table of Comparison

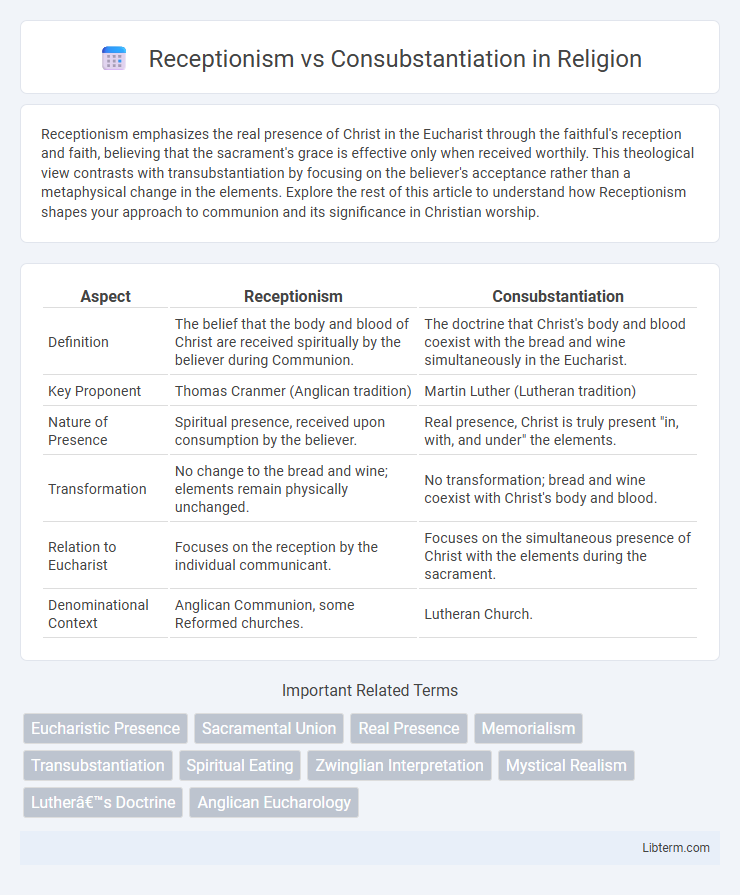

| Aspect | Receptionism | Consubstantiation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The belief that the body and blood of Christ are received spiritually by the believer during Communion. | The doctrine that Christ's body and blood coexist with the bread and wine simultaneously in the Eucharist. |

| Key Proponent | Thomas Cranmer (Anglican tradition) | Martin Luther (Lutheran tradition) |

| Nature of Presence | Spiritual presence, received upon consumption by the believer. | Real presence, Christ is truly present "in, with, and under" the elements. |

| Transformation | No change to the bread and wine; elements remain physically unchanged. | No transformation; bread and wine coexist with Christ's body and blood. |

| Relation to Eucharist | Focuses on the reception by the individual communicant. | Focuses on the simultaneous presence of Christ with the elements during the sacrament. |

| Denominational Context | Anglican Communion, some Reformed churches. | Lutheran Church. |

Introduction to Receptionism and Consubstantiation

Receptionism, a doctrine primarily associated with Reformed theology, asserts that the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist occurs spiritually during the act of faith by the believer, distinct from the physical elements themselves. Consubstantiation, often linked to Lutheran belief, holds that Christ's body and blood coexist "in, with, and under" the bread and wine, maintaining a physical presence alongside the elements. Both concepts address the mystery of Christ's presence in Communion, differing fundamentally in their understanding of how the elements function in the sacrament.

Historical Background of Eucharistic Doctrines

The historical background of Eucharistic doctrines reveals that Receptionism emerged primarily during the Reformation as a response to debates on the Real Presence, emphasizing the believer's reception of Christ's body and blood spiritually rather than physically. Consubstantiation, often attributed to Lutheran theology, asserts the coexistence of Christ's body and blood with the bread and wine, tracing roots back to Martin Luther's efforts to counter both Catholic transubstantiation and Reformed symbolic interpretations. These theological positions reflect significant shifts in 16th-century Christian thought about the nature and presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Defining Receptionism: Core Beliefs and Origins

Receptionism, rooted in certain Protestant traditions, particularly Lutheranism, asserts that the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist occurs through the faith of the communicant rather than the elements themselves transforming. This doctrine emphasizes that the bread and wine remain unchanged physically, but believers receive Christ spiritually by faith during communion. Originating as a theological response to debates on the Lord's Supper, Receptionism contrasts with Consubstantiation by rejecting any metaphysical change in the elements while affirming Christ's true presence through reception.

Understanding Consubstantiation: Key Principles

Consubstantiation is a theological concept in Christian Eucharistic doctrine asserting that the substance of Christ's body and blood coexists with the bread and wine during Communion, rather than replacing them. Unlike Receptionism, which emphasizes faith-based reception of Christ's presence by believers, consubstantiation maintains a literal presence of Christ alongside the physical elements. This doctrine is principally associated with Lutheran theology and underscores the mystery of Christ's true presence without transmutation of the elements.

Scriptural Foundations for Each Doctrine

Receptionism finds its scriptural foundation primarily in 1 Corinthians 11:27-29, emphasizing the communicant's worthy reception of the Eucharist, interpreting Christ's presence as received by faith during communion. Consubstantiation relies on passages such as John 6:51-58 and Luke 22:19-20, highlighting Christ's real presence "in, with, and under" the bread and wine, asserting a tangible union without transubstantiation. Both doctrines seek biblical validation for Christ's presence in the Lord's Supper but differ in the nature and moment of that presence according to their scriptural interpretations.

Comparing Theological Implications

Receptionism posits that Christ's presence in the Eucharist occurs only when communicants receive the elements in faith, emphasizing the role of individual belief in actualizing the sacrament's efficacy. Consubstantiation holds that Christ's body and blood coexist substantively with the bread and wine during the Eucharist, underscoring an objective, continuous presence independent of the recipient's faith. Theologically, Receptionism highlights subjective faith as essential for grace, while Consubstantiation affirms a metaphysical union sustaining Christ's real presence during the sacramental act.

Influence on Liturgical Practices

Receptionism emphasizes the believer's faith in the Eucharist, shaping liturgical practices to focus on personal reception and spiritual participation. Consubstantiation teaches the coexistence of Christ's body and blood with the bread and wine, influencing rituals to affirm the real presence during Communion. Both doctrines impact the frequency, reverence, and theological emphasis observed in liturgical celebrations across denominations.

Prominent Supporters and Critics

Receptionism, primarily supported by Protestant reformers like Martin Bucer, posits that Christ's body and blood are received spiritually by faith during communion, contrasting with the Lutheran doctrine of consubstantiation, championed by Martin Luther himself, which holds that Christ's body and blood coexist "in, with, and under" the bread and wine. Critics of receptionism, such as Johann Gerhard, argue it diminishes the real presence, while opponents of consubstantiation, including Reformed theologians like John Calvin, reject any physical or substantial coexistence, emphasizing a spiritual presence instead. The debate reflects broader theological divisions on the Eucharist's nature, impacting liturgical practices and ecclesiastical affiliations across Protestant traditions.

Receptionism vs Consubstantiation: Contemporary Relevance

Receptionism asserts that Christ's body and blood are received spiritually by the believer during communion without any physical presence in the elements, emphasizing faith's role in the sacrament. Consubstantiation teaches that Christ's body and blood coexist with the bread and wine, presenting a real, mystical presence without altering the substances, which preserves a tangible sacramental encounter. Contemporary relevance lies in ongoing theological debates concerning the nature of Christ's presence in the Eucharist, influencing denominational worship practices and ecumenical dialogues.

Conclusion: Evaluating Doctrinal Significance

Receptionism emphasizes the believer's faith as the moment of Christ's real presence in communion, highlighting subjective reception over objective transformation. Consubstantiation asserts the coexistence of Christ's body and blood with the bread and wine, emphasizing an objective metaphysical union in the Eucharist. Evaluating doctrinal significance involves assessing how each view shapes sacramental theology, piety, and ecclesial identity within various Christian traditions.

Receptionism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com