Arian is a name with diverse cultural significance, often associated with qualities like nobility and wisdom. Its rich historical roots span various regions, from ancient Persia to modern usage, symbolizing strength and honor. Discover more about the origins and meanings of Arian in the rest of this article.

Table of Comparison

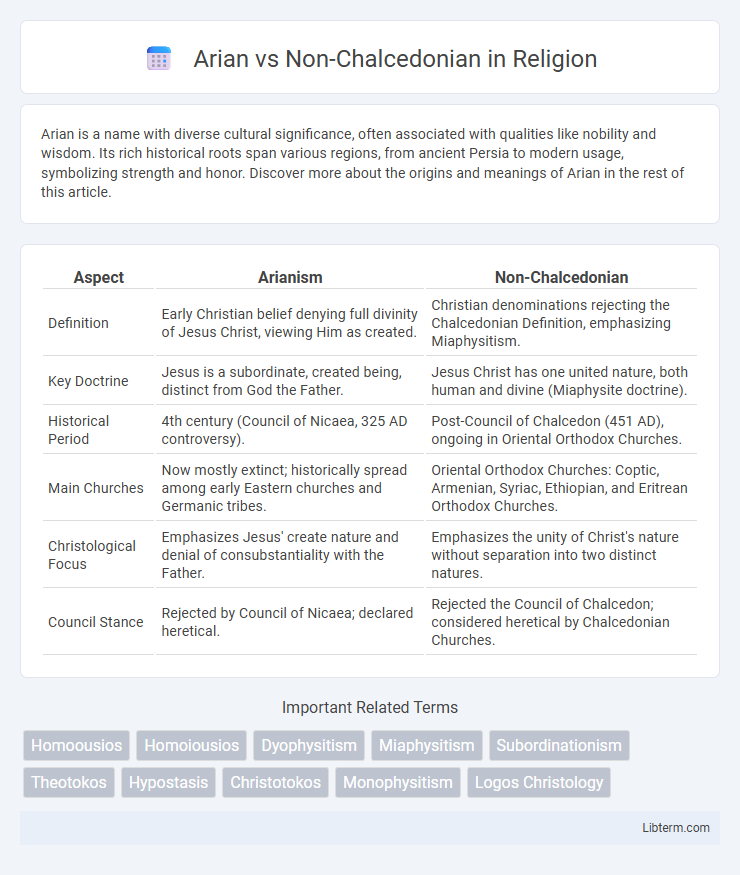

| Aspect | Arianism | Non-Chalcedonian |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Early Christian belief denying full divinity of Jesus Christ, viewing Him as created. | Christian denominations rejecting the Chalcedonian Definition, emphasizing Miaphysitism. |

| Key Doctrine | Jesus is a subordinate, created being, distinct from God the Father. | Jesus Christ has one united nature, both human and divine (Miaphysite doctrine). |

| Historical Period | 4th century (Council of Nicaea, 325 AD controversy). | Post-Council of Chalcedon (451 AD), ongoing in Oriental Orthodox Churches. |

| Main Churches | Now mostly extinct; historically spread among early Eastern churches and Germanic tribes. | Oriental Orthodox Churches: Coptic, Armenian, Syriac, Ethiopian, and Eritrean Orthodox Churches. |

| Christological Focus | Emphasizes Jesus' create nature and denial of consubstantiality with the Father. | Emphasizes the unity of Christ's nature without separation into two distinct natures. |

| Council Stance | Rejected by Council of Nicaea; declared heretical. | Rejected the Council of Chalcedon; considered heretical by Chalcedonian Churches. |

Introduction to Early Christian Christological Debates

The Arian controversy revolved around the nature of Christ's divinity, asserting that Jesus was a created being distinct from God the Father, a view condemned at the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. Non-Chalcedonian Christians rejected the Chalcedonian Definition of 451 AD, which affirmed Christ's dual nature as fully divine and fully human, advocating instead for a miaphysite understanding of Christ's single, unified nature. These early Christological debates significantly shaped the development of Christian doctrine and led to enduring schisms within Eastern Christianity.

Defining Arianism: Origins and Core Beliefs

Arianism originated in the early 4th century, founded by Arius, a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, who taught that Jesus Christ was a created being distinct from and subordinate to God the Father. This theological perspective denied the co-eternity and consubstantiality of the Son with the Father, emphasizing a hierarchical relationship within the Trinity. Arianism fundamentally challenged the doctrine of the Trinity by asserting that the Son was not equal to the Father, a belief that was later declared heretical by the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

The Emergence of Non-Chalcedonian Christianity

Non-Chalcedonian Christianity emerged in the 5th century as a response to the Council of Chalcedon's definition of Christ's dual nature, rejecting the Chalcedonian formula that affirmed Jesus as both fully divine and fully human in one person. This distinct theological stance contrasted with earlier Arianism, which denied Christ's full divinity, asserting instead that the Son was a created being subordinate to the Father. Non-Chalcedonian churches, including the Coptic, Syriac, and Armenian traditions, emphasize a miaphysite Christology, highlighting the united divine and human nature of Christ as essential to their ecclesiastical identity and doctrinal development.

Key Differences: Arianism vs Non-Chalcedonian Doctrines

Arianism asserts that Jesus Christ is a created being distinct from and subordinate to God the Father, denying the full divinity of Christ, while Non-Chalcedonian doctrines reject the Chalcedonian definition of Christ's dual nature, emphasizing a single, united nature of Christ either divine or a synthesis of divine and human. Arians maintain a hierarchical Trinity with the Son as subordinate, contrasting sharply with Non-Chalcedonians who uphold the unity of Christ's nature without division or separation. The theological divergence centers on Christology: Arianism denies consubstantiality with the Father, whereas Non-Chalcedonian beliefs reject the dual nature established at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD.

Historical Context: Councils and Schisms

The Arian controversy emerged in the early 4th century, centered on the Council of Nicaea (325 AD), which condemned Arius's teachings that denied the full divinity of Christ, establishing the Nicene Creed as orthodox doctrine. Non-Chalcedonian churches rejected the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD), opposing its definition of Christ having two natures, leading to significant schisms and the formation of Oriental Orthodox communions such as the Coptic, Armenian, and Syriac churches. These historical councils and subsequent schisms deeply shaped Christian theological divisions by defining pivotal Christological doctrines that differentiated Arianism, Chalcedonian orthodoxy, and Non-Chalcedonian traditions.

Prominent Figures: Arius and Non-Chalcedonian Leaders

Arius, a 4th-century Alexandrian priest, was the central figure behind Arianism, which argued that Jesus Christ was a created being distinct from God the Father, leading to the Arian controversy and the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. Prominent Non-Chalcedonian leaders include Severus of Antioch and Dioscorus of Alexandria, who rejected the Council of Chalcedon's 451 AD definition of Christ's dual nature, advocating instead for Miaphysitism. These figures significantly shaped early Christian theological debates on the nature of Christ, influencing their respective religious traditions.

Theological Controversies and Scriptural Interpretations

Arianism contends that Jesus Christ is a created being distinct from God the Father, emphasizing Christ's subordinate status and challenging the doctrine of the Trinity established by the Nicene Creed. Non-Chalcedonian Christians reject the Chalcedonian Definition's two natures of Christ, advocating instead for a miaphysite understanding that Christ possesses one united divine-human nature, which affects their interpretation of key scriptural passages like John 1:14 and Colossians 2:9. These theological controversies hinge on Christological debates regarding the nature and personhood of Christ, shaping divergent readings of biblical texts related to incarnation and divinity.

Spread and Influence of Arianism in the Early Church

Arianism spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire during the 4th century, gaining significant influence among Germanic tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, and Lombards, who adopted Arian Christianity as their dominant faith. Its doctrinal emphasis on the distinct and subordinate nature of the Son in relation to the Father contrasted sharply with the Non-Chalcedonian position, which rejected the Council of Chalcedon's definition and emphasized the unity of Christ's nature. The widespread adoption of Arianism by key political groups challenged the Nicene orthodoxy and shaped theological and ecclesiastical conflicts in early Christianity.

Non-Chalcedonian Communities and Their Legacy

Non-Chalcedonian communities, including the Oriental Orthodox Churches such as the Coptic, Armenian, and Syriac Orthodox, rejected the Council of Chalcedon's definition in 451 AD, emphasizing a Miaphysite Christology that affirms one united nature of Christ. Their theological stance fostered distinctive liturgical traditions, ecclesiastical structures, and artistic expressions that continue to influence Christian worship and identity in the Middle East and Northeast Africa. The legacy of these communities persists in their resilience amid persecution and their role in preserving ancient Christian languages and manuscripts, shaping the cultural and religious landscape beyond Chalcedonian Christianity.

Lasting Impact on Christian Doctrine and Denominations

Arianism, which denied the full divinity of Christ, was largely deemed heretical at the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, but its emphasis on the nature of Christ spurred extensive theological debate shaping the Nicene Creed. Non-Chalcedonian churches, rejecting the Council of Chalcedon's definition of Christ having two natures, led to the formation of distinct Oriental Orthodox denominations such as the Coptic, Armenian, and Syriac Orthodox Churches. The lasting impact of both Arianism and Non-Chalcedonian positions is seen in the enduring doctrinal divisions that continue to influence Christian theology and denominational identities today.

Arian Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com