Chalcedonian doctrine defines the dual nature of Christ as both fully divine and fully human, a cornerstone of orthodox Christian theology established at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD. Understanding Chalcedonian Christology is essential for grasping key historical and theological debates within Christianity. Discover how this doctrine shaped faith and practice by reading the rest of the article.

Table of Comparison

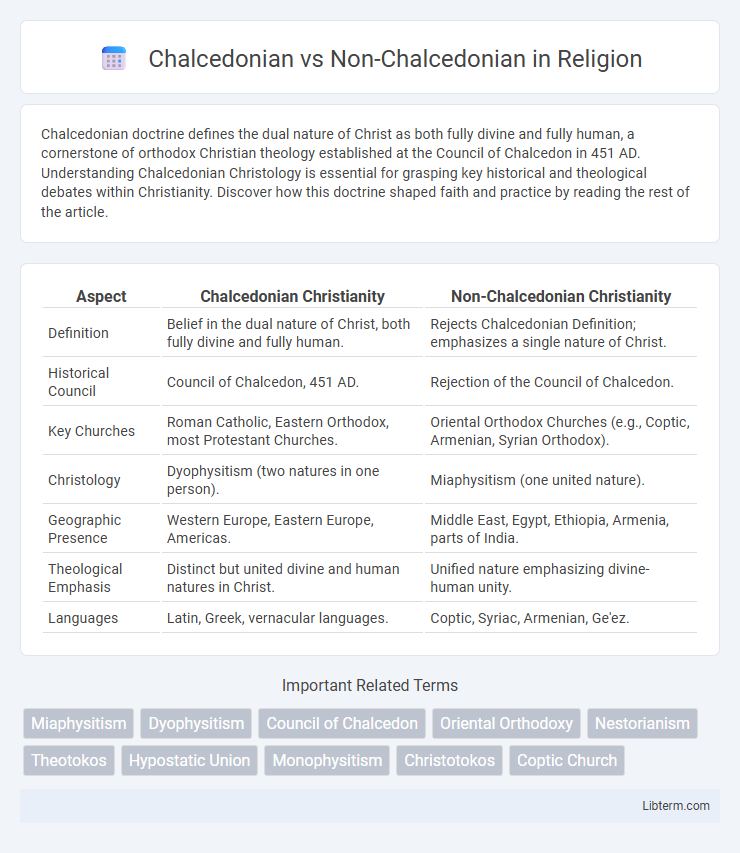

| Aspect | Chalcedonian Christianity | Non-Chalcedonian Christianity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Belief in the dual nature of Christ, both fully divine and fully human. | Rejects Chalcedonian Definition; emphasizes a single nature of Christ. |

| Historical Council | Council of Chalcedon, 451 AD. | Rejection of the Council of Chalcedon. |

| Key Churches | Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, most Protestant Churches. | Oriental Orthodox Churches (e.g., Coptic, Armenian, Syrian Orthodox). |

| Christology | Dyophysitism (two natures in one person). | Miaphysitism (one united nature). |

| Geographic Presence | Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Americas. | Middle East, Egypt, Ethiopia, Armenia, parts of India. |

| Theological Emphasis | Distinct but united divine and human natures in Christ. | Unified nature emphasizing divine-human unity. |

| Languages | Latin, Greek, vernacular languages. | Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Ge'ez. |

Introduction to Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian Christianity

Chalcedonian Christianity adheres to the doctrine established at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, affirming the dual nature of Christ as fully divine and fully human in one person. Non-Chalcedonian Christianity, often called Oriental Orthodoxy, rejects this definition, emphasizing a single, unified nature of Christ known as Miaphysitism. These theological distinctions led to significant historical schisms, shaping distinct liturgical traditions and ecclesiastical structures within Christian history.

Historical Context: The Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD defined the dual nature of Christ as fully divine and fully human, shaping Chalcedonian Christianity's theological framework. Non-Chalcedonian churches, including the Oriental Orthodox, rejected this definition, adhering to Miaphysitism which emphasizes the single united nature of Christ. This schism established enduring doctrinal divisions influencing Christian history and denominations in the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East.

Key Theological Differences

Chalcedonian Christianity adheres to the definition established by the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, affirming that Jesus Christ possesses two distinct natures--fully divine and fully human--united in one person without confusion or separation. Non-Chalcedonian churches, often referred to as Oriental Orthodox, reject this dyophysite formula, instead espousing miaphysitism, which holds that Christ has one united nature that is both divine and human. This fundamental Christological divergence impacts doctrines on the incarnation, the nature of salvation, and ecclesiastical identity between Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian traditions.

Christological Doctrines Explained

Chalcedonian Christology affirms the doctrine of the hypostatic union, asserting that Jesus Christ possesses two distinct natures, divine and human, united in one person without confusion or separation. Non-Chalcedonian churches reject this definition, emphasizing a miaphysite understanding, where Christ's nature is one composite unity of divine and human elements inseparably united. The key theological divergence lies in the interpretation of Christ's nature(s), shaping differing ecclesiastical traditions within Christianity.

Major Chalcedonian Churches

The Major Chalcedonian Churches, including the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and most Protestant denominations, adhere to the doctrine established at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, which defines Christ as having two distinct natures, fully divine and fully human, united in one person. These churches reject the Non-Chalcedonian position held by Oriental Orthodox churches, which emphasize a miaphysite theology asserting one united nature of Christ. The Chalcedonian definition remains a cornerstone for ecumenical dialogue and theological identity within these traditions.

Prominent Non-Chalcedonian Churches

Prominent Non-Chalcedonian Churches include the Oriental Orthodox family, such as the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church. These churches reject the Chalcedonian Definition of 451 AD, emphasizing a Miaphysite Christology that affirms the unity of Christ's divine and human natures without separation. Their distinct theological stance led to enduring divisions from Chalcedonian churches, influencing Christian doctrinal development and ecclesiastical organization in the Near East and Africa.

Political and Cultural Impacts

The Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian schisms shaped the political landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean by aligning ecclesiastical identities with emerging state powers. Chalcedonian Christianity, embraced by the Byzantine Empire, reinforced imperial authority and centralized governance, while Non-Chalcedonian churches, such as the Coptic and Armenian Apostolic Churches, fostered distinct national identities and cultural autonomy. These religious divisions contributed to enduring geopolitical tensions and influenced the cultural heritage, language preservation, and artistic expressions within their respective communities.

Efforts Toward Reconciliation

Efforts toward reconciliation between Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian churches have centered on theological dialogues that emphasize shared beliefs in Christ's divinity and humanity while addressing differences in Christological terminology. Joint commissions, such as those between the Roman Catholic and Oriental Orthodox Churches, have produced statements acknowledging common faith in the one incarnate Word of God, helping to bridge centuries-old divides. These ecumenical initiatives promote mutual respect and understanding, fostering unity without requiring doctrinal conformity.

Lasting Effects on Christian Unity

The division between Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian Christians, originating from the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, created enduring theological rifts that persist in various Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. These doctrinal disagreements over the nature of Christ continue to influence ecclesiastical relationships, hindering full communion and cooperation among Christian denominations. The Chalcedonian definition shaped the mainstream Christian orthodoxy, while Non-Chalcedonian traditions maintain distinct liturgical practices and theological interpretations, reinforcing a lasting fragmentation within global Christianity.

Contemporary Relevance and Dialogue

Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian churches remain distinct in Christological doctrines, yet ongoing ecumenical dialogues emphasize mutual recognition and theological convergence, fostering contemporary Christian unity. These conversations address millennia-old schisms by exploring shared beliefs and clarified doctrinal expressions, promoting intercommunion and joint social witness efforts. Enhanced understanding between Chalcedonian traditions (Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic) and Non-Chalcedonian communities (Oriental Orthodox) facilitates collaborative responses to modern ethical and cultural challenges.

Chalcedonian Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com