Nestorianism is a Christian theological doctrine emphasizing the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ, historically associated with Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople. This belief led to significant controversy and was deemed heretical by the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, resulting in a major schism within early Christianity. Explore the rest of this article to understand the origins, beliefs, and lasting impact of Nestorianism on religious history.

Table of Comparison

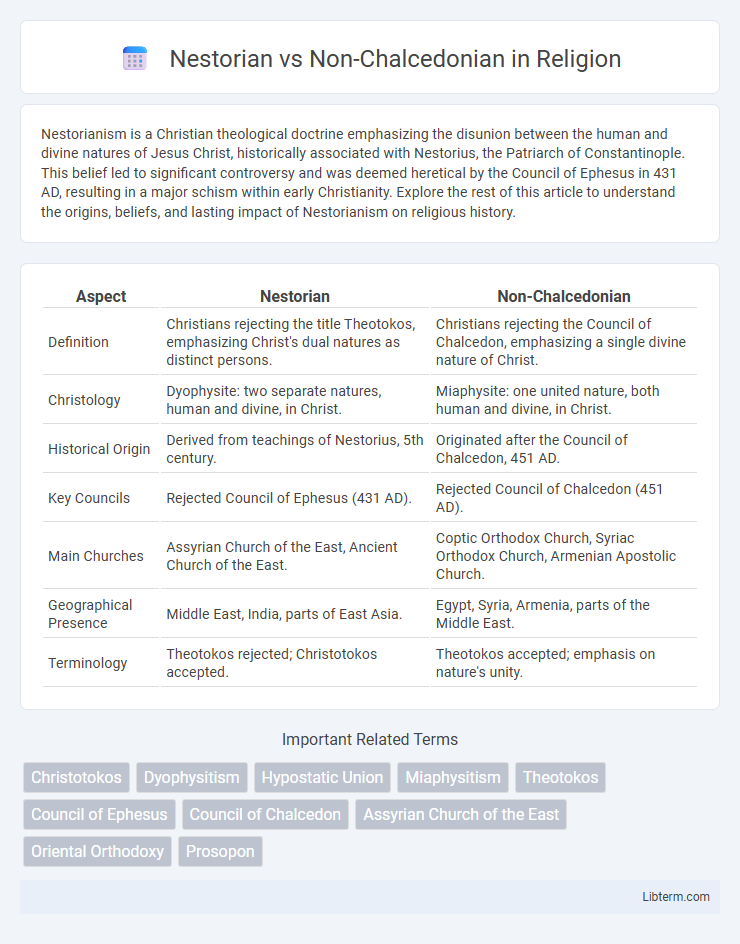

| Aspect | Nestorian | Non-Chalcedonian |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Christians rejecting the title Theotokos, emphasizing Christ's dual natures as distinct persons. | Christians rejecting the Council of Chalcedon, emphasizing a single divine nature of Christ. |

| Christology | Dyophysite: two separate natures, human and divine, in Christ. | Miaphysite: one united nature, both human and divine, in Christ. |

| Historical Origin | Derived from teachings of Nestorius, 5th century. | Originated after the Council of Chalcedon, 451 AD. |

| Key Councils | Rejected Council of Ephesus (431 AD). | Rejected Council of Chalcedon (451 AD). |

| Main Churches | Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East. | Coptic Orthodox Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Armenian Apostolic Church. |

| Geographical Presence | Middle East, India, parts of East Asia. | Egypt, Syria, Armenia, parts of the Middle East. |

| Terminology | Theotokos rejected; Christotokos accepted. | Theotokos accepted; emphasis on nature's unity. |

Introduction to Nestorianism and Non-Chalcedonianism

Nestorianism, originating in the teachings of Nestorius, emphasizes the distinction between the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ, rejecting the title Theotokos for Mary. Non-Chalcedonianism, also known as Oriental Orthodoxy, rejects the Council of Chalcedon's definition of two natures in Christ and adheres to a miaphysite understanding of a united divine-human nature. These theological differences shape the distinct Christological doctrines and ecclesiastical traditions within early Christianity.

Historical Background and Origins

Nestorian Christianity originated in the 5th century, emphasizing the distinction between the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ, rooted in the teachings of Nestorius, the Archbishop of Constantinople. Non-Chalcedonian churches, also known as Oriental Orthodox, rejected the Council of Chalcedon's definition in 451 AD, advocating for a miaphysite understanding that affirms one united nature of Christ. These theological divergences led to early schisms, with Nestorianism spreading primarily in Persia and Asia, while Non-Chalcedonian communities developed mainly in Egypt, Syria, and Armenia.

Key Theological Differences

Nestorianism emphasizes the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ, asserting two separate persons, which contrasts sharply with Non-Chalcedonian theology that rejects the Chalcedonian Definition and promotes the idea of a single, united nature (miaphysis). Non-Chalcedonian churches, such as the Oriental Orthodox, emphasize the one incarnate nature of the Word of God, opposing the Nestorian bifurcation and Chalcedonian dyophysitism that distinguishes between two persons or natures. This fundamental difference impacts Christological interpretations related to the unity and duality of Christ's nature, shaping ecclesiastical identity and doctrinal stances within Eastern Christianity.

Christological Controversies Explained

The Nestorian controversy centers on whether Christ has two separate persons, affirming a distinction between Christ's human and divine natures, a view condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431. Non-Chalcedonian churches reject the Chalcedonian Definition of 451, emphasizing a miaphysite understanding where Christ's divine and human natures are united in one nature without confusion or separation. These Christological debates shaped the doctrinal splits between the Church of the East, which aligns with Nestorian theology, and Oriental Orthodox Churches, which hold to Non-Chalcedonian Christology.

Major Councils Involved: Ephesus and Chalcedon

The Nestorian controversy centered on the Council of Ephesus (431 AD), which condemned Nestorius's teaching that Christ existed as two separate persons, affirming instead the unity of Christ's person. Non-Chalcedonian churches rejected the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD), which declared Christ's dual nature as fully divine and fully human in one person, viewing it as a deviation from the true faith. These councils shaped major doctrinal divisions, with the Council of Ephesus addressing Christological unity and Chalcedon defining the dual nature of Christ.

Principal Figures and Leaders

Nestorianism, primarily associated with Nestorius, the Archbishop of Constantinople in the early 5th century, emphasized the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus Christ, leading to opposition by figures like Cyril of Alexandria. Non-Chalcedonian churches, including the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church, rejected the Council of Chalcedon's definition and were led by key figures such as Dioscorus of Alexandria and Severus of Antioch. These leaders shaped distinct Christological doctrines that defined the theological and ecclesiastical separation between Nestorians and Non-Chalcedonians in early Christianity.

Regional Spread and Influence

Nestorian Christianity primarily spread across Persia, Central Asia, and parts of India and China, influencing the Church of the East and fostering extensive missionary activity along the Silk Road. Non-Chalcedonian churches, often referred to as Oriental Orthodox, have strong historical roots in Egypt, Ethiopia, Armenia, and Syria, maintaining distinctive theological and liturgical traditions separate from Chalcedonian Christianity. The Nestorian Church's regional influence declined after the rise of Islam, while Non-Chalcedonian communities remain pivotal in these Middle Eastern and African regions with enduring cultural and religious impact.

Response from the Wider Christian World

The Wider Christian World largely rejected Nestorianism for its perceived division of Christ's human and divine natures, leading to its condemnation at the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD and subsequent marginalization within mainstream Christianity. Non-Chalcedonian churches, often called Oriental Orthodox, rejected the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD) for its definition of Christ's dual nature, fostering theological and ecclesiastical separation but maintained significant regional influence and respected apostolic traditions. Both groups faced isolation from the dominant Chalcedonian churches, shaping centuries of religious and political dynamics in Eastern Christianity.

Lasting Impact on Eastern Christianity

Nestorianism, emphasizing the distinctiveness of Christ's two natures, significantly influenced the Church of the East, shaping Eastern Christianity's theological landscape and missionary activities across Asia. Non-Chalcedonian churches, rejecting the Council of Chalcedon's definition, preserved Oriental Orthodox traditions, maintaining rich liturgical and theological diversity within Eastern Christianity. Both movements contributed to the enduring plurality and complex doctrinal heritage of Eastern Christian communities beyond Byzantine influence.

Modern Perspectives and Ecumenical Dialogues

Modern perspectives on Nestorian and Non-Chalcedonian traditions increasingly emphasize theological nuances and historical contexts, promoting mutual respect and understanding. Ecumenical dialogues, particularly through forums like the World Council of Churches, focus on Christological clarifications and shared faith experiences to bridge ancient doctrinal divisions. Recent agreements highlight reconciliations between the Assyrian Church of the East and Oriental Orthodox Churches, advancing unity efforts within global Christianity.

Nestorian Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com