Metaplasia is a reversible cellular process where one mature cell type changes into another type, often as an adaptive response to chronic irritation or inflammation. This alteration can serve as a protective mechanism but may increase the risk of developing dysplasia and cancer if the underlying cause persists. Explore the rest of this article to understand how metaplasia affects your health and when medical intervention is necessary.

Table of Comparison

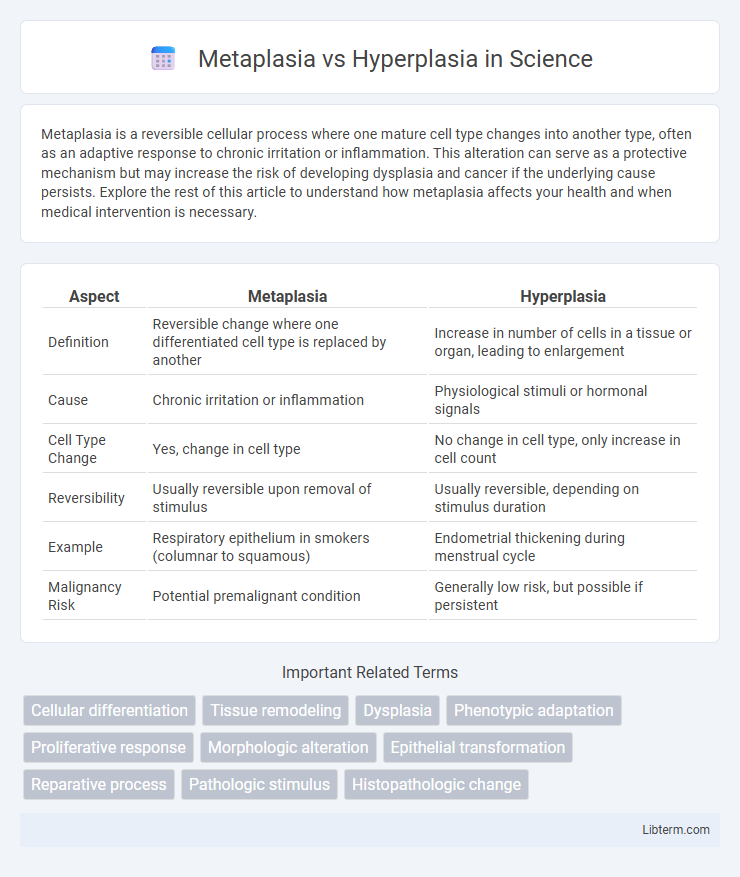

| Aspect | Metaplasia | Hyperplasia |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Reversible change where one differentiated cell type is replaced by another | Increase in number of cells in a tissue or organ, leading to enlargement |

| Cause | Chronic irritation or inflammation | Physiological stimuli or hormonal signals |

| Cell Type Change | Yes, change in cell type | No change in cell type, only increase in cell count |

| Reversibility | Usually reversible upon removal of stimulus | Usually reversible, depending on stimulus duration |

| Example | Respiratory epithelium in smokers (columnar to squamous) | Endometrial thickening during menstrual cycle |

| Malignancy Risk | Potential premalignant condition | Generally low risk, but possible if persistent |

Introduction to Metaplasia and Hyperplasia

Metaplasia and hyperplasia are cellular adaptations to stress or injury that involve changes in cell type and cell number, respectively. Metaplasia refers to the reversible replacement of one differentiated cell type with another, often as a protective response to chronic irritation or inflammation. Hyperplasia involves an increase in the number of cells within a tissue or organ, typically resulting from increased functional demand or hormonal stimulation.

Defining Metaplasia

Metaplasia is a reversible cellular adaptation where one differentiated cell type is replaced by another mature cell type, often as a response to chronic irritation or inflammation. This process differs from hyperplasia, which involves an increase in the number of cells within a tissue, leading to tissue enlargement without a change in cell type. Understanding metaplasia is crucial in pathology because it can precede dysplasia and malignant transformation under persistent adverse conditions.

Defining Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia refers to an increase in the number of cells within a tissue or organ, leading to its enlargement, often as a physiological or pathological response to stimuli. Unlike metaplasia, which involves the transformation of one differentiated cell type into another, hyperplasia involves proliferation of cells that are normal in type but increased in quantity. Common examples of hyperplasia include endometrial hyperplasia caused by excess estrogen and benign prostatic hyperplasia in aging males.

Key Differences Between Metaplasia and Hyperplasia

Metaplasia involves the reversible transformation of one differentiated cell type into another, often as an adaptive response to chronic irritation, while hyperplasia refers to an increase in the number of cells within a tissue or organ, leading to tissue enlargement. Metaplasia changes cell type without increasing cell number, contrasting with hyperplasia, which involves cell proliferation without changing cell type. Both processes are potentially reversible but have different implications for pathology and disease progression.

Causes of Metaplasia

Metaplasia is primarily caused by chronic irritation or inflammation, often due to factors such as tobacco smoke, gastroesophageal reflux, or persistent infections, which trigger a reversible change in cell type to better withstand stress. Hyperplasia results from increased physiological demand or hormonal stimulation, leading to an increase in the number of cells rather than a change in cell type. The adaptive response in metaplasia aims to protect underlying tissues but may predispose to dysplasia and malignancy if the irritative stimulus persists.

Causes of Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia results from increased cellular proliferation due to stimuli such as hormonal imbalances, chronic inflammation, or prolonged tissue injury. Common causes include excessive estrogen exposure leading to endometrial hyperplasia, chronic irritation in the respiratory tract causing bronchial hyperplasia, and compensatory mechanisms following tissue loss. Unlike metaplasia, which involves a reversible change in cell type, hyperplasia specifically involves an increase in the number of cells within a tissue.

Clinical Examples of Metaplasia

Metaplasia involves the reversible transformation of one differentiated cell type to another, commonly seen in respiratory epithelium where chronic smoking induces squamous metaplasia as a protective response. Barrett's esophagus represents another classical example, characterized by the replacement of normal squamous epithelium with intestinal-type columnar cells due to chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. These adaptive changes highlight metaplasia's role in protecting tissue but also its potential progression to dysplasia and malignancy if the injurious stimulus persists.

Clinical Examples of Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia is characterized by an increased number of cells in an organ or tissue and can be stimulated by hormonal or growth factor signals, commonly observed in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) where prostate gland enlargement causes urinary symptoms. Another prevalent example includes endometrial hyperplasia, often resulting from prolonged estrogen exposure without progesterone, leading to abnormal thickening of the uterine lining and potential progression to endometrial carcinoma. Unlike metaplasia, which involves cellular transformation from one type to another, hyperplasia maintains normal cell type but with increased proliferation driven by physiological or pathological stimuli.

Diagnostic Approaches

Diagnostic approaches for metaplasia primarily involve histopathological examination through biopsy, where cellular morphology reveals a reversible change in cell type due to chronic irritation. Hyperplasia is diagnosed by identifying an increased number of normal cells in tissue samples, often through microscopic analysis and immunohistochemical staining to distinguish reactive from neoplastic proliferation. Advanced imaging modalities such as endoscopy or ultrasound complement tissue diagnosis by detecting structural changes indicative of metaplasia or hyperplasia.

Implications for Disease Progression and Treatment

Metaplasia involves the reversible transformation of one differentiated cell type to another, often as an adaptive response to chronic irritation, increasing the risk of dysplasia and malignancy if persistent. Hyperplasia is characterized by an increased number of cells in an organ or tissue, frequently as a compensatory mechanism, which may predispose to neoplastic growth when regulation fails. Understanding these cellular changes is critical for diagnosing disease progression and tailoring treatments, as metaplasia may require addressing underlying irritants while hyperplasia often responds to hormonal or growth factor modulation.

Metaplasia Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com