The Mandate of Heaven is an ancient Chinese political and religious doctrine used to justify the rule of the emperor, asserting that heaven grants the right to govern based on virtue and moral conduct. When a ruler becomes despotic or fails to fulfill his duties, it is believed that the Mandate is revoked, legitimizing rebellion and the rise of a new dynasty. Explore the rest of the article to understand how this concept shaped Chinese history and governance over centuries.

Table of Comparison

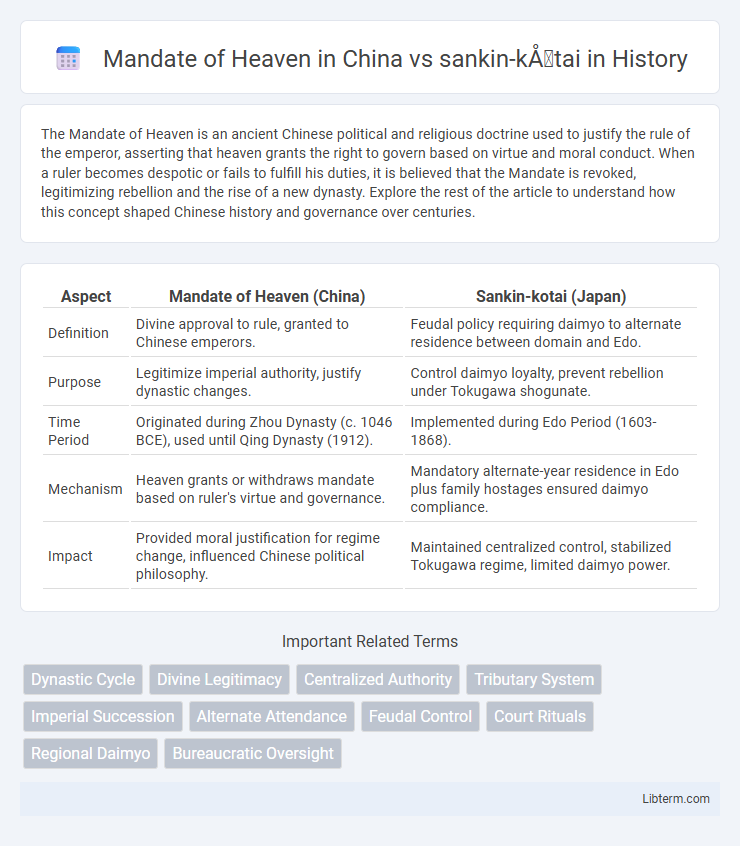

| Aspect | Mandate of Heaven (China) | Sankin-kotai (Japan) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Divine approval to rule, granted to Chinese emperors. | Feudal policy requiring daimyo to alternate residence between domain and Edo. |

| Purpose | Legitimize imperial authority, justify dynastic changes. | Control daimyo loyalty, prevent rebellion under Tokugawa shogunate. |

| Time Period | Originated during Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046 BCE), used until Qing Dynasty (1912). | Implemented during Edo Period (1603-1868). |

| Mechanism | Heaven grants or withdraws mandate based on ruler's virtue and governance. | Mandatory alternate-year residence in Edo plus family hostages ensured daimyo compliance. |

| Impact | Provided moral justification for regime change, influenced Chinese political philosophy. | Maintained centralized control, stabilized Tokugawa regime, limited daimyo power. |

Understanding the Mandate of Heaven: Ancient China’s Divine Right

The Mandate of Heaven in ancient China served as a divine justification for imperial rule, granting emperors the right to govern based on moral virtue and the favor of heaven, with natural disasters or social unrest indicating a loss of this mandate. In contrast, the Japanese sankin-kotai system was a political strategy during the Edo period, requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo to ensure loyalty to the shogun rather than a divine endorsement of authority. Understanding the Mandate of Heaven reveals how ancient Chinese rulers legitimized their sovereignty through cosmic and ethical considerations, whereas sankin-kotai functioned as a practical mechanism to maintain centralized feudal control.

Origins and Principles of the Mandate of Heaven

The Mandate of Heaven, originating during the Zhou Dynasty, established the divine right to rule based on virtue and moral conduct, legitimizing a ruler's authority only as long as they governed justly and maintained harmony. In contrast, the sankin-kotai system of Tokugawa Japan was a political strategy mandating daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and the shogun's court, designed to ensure loyalty and control rather than justify sovereignty through moral or divine approval. The Mandate of Heaven embodies a principle blending spirituality and ethics in governance, whereas sankin-kotai reflects pragmatic feudal regulation without invoking divine sanction.

The Role of the Mandate of Heaven in Dynastic Cycles

The Mandate of Heaven played a crucial role in Chinese dynastic cycles by legitimizing the rise and fall of emperors based on virtue, prosperity, and moral conduct, signifying divine approval or withdrawal thereof. In contrast, sankin-kotai was a Tokugawa shogunate policy designed to control daimyo through regular alternate attendance in Edo, emphasizing political control rather than divine legitimacy. The Mandate of Heaven framed political authority as contingent on heaven's favor, influencing social stability and the justification of rebellion during dynastic transitions.

Overview of Sankin-kōtai: The Edo Period’s Control Mechanism

Sankin-kotai was a strategic policy implemented during Japan's Edo period requiring daimyo (feudal lords) to alternate residence between their domains and the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo, ensuring loyalty and preventing rebellion. This system functioned as a political control mechanism by draining the financial resources of daimyo through the costly travel and maintenance of two residences, weakening their capacity to challenge the shogunate's authority. In contrast, the Mandate of Heaven in China operated as a divine justification for rulers, where the legitimacy of emperors depended on moral governance and the ability to maintain harmony, rather than enforced political control through residence requirements.

How Sankin-kōtai Structured Tokugawa Japan’s Feudal Society

The Mandate of Heaven justified the divine right of Chinese emperors to rule, emphasizing moral governance and cyclical dynastic changes, while Sankin-kotai was a strategic policy in Tokugawa Japan requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo to ensure loyalty. Sankin-kotai structured Tokugawa Japan's feudal society by centralizing political power, reducing regional autonomy, and facilitating economic integration through mandated daimyo processions and residence obligations. This system reinforced the shogunate's control over the daimyo, promoting political stability and social order during the Edo period.

Comparing Legitimacy: Divine Authority vs. Political Control

The Mandate of Heaven in China established imperial legitimacy through divine authority, asserting that emperors ruled by heavenly will contingent on moral governance and stability. In contrast, Japan's sankin-kotai system reinforced political control by requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, ensuring loyalty to the shogunate through strategic oversight rather than divine sanction. Whereas the Mandate projected a cosmic moral order underpinning sovereignty, sankin-kotai emphasized practical mechanisms for centralized political dominance and social order.

Societal Impact: Mandate of Heaven and Chinese Governance

The Mandate of Heaven served as a divine justification for Chinese emperors, reinforcing centralized authority while allowing rebellion when rulers became tyrannical, thus shaping a dynamic governance model that prioritized moral legitimacy. This concept fostered societal stability by embedding the ruler's responsibility to ensure harmony, justice, and prosperity, influencing the bureaucratic structure and political accountability in imperial China. In contrast, sankin-kotai in Japan primarily enforced daimyo loyalty through alternate residence requirements, focusing more on political control than moral governance.

Societal Impact: Sankin-kōtai and Japanese Centralization

The Mandate of Heaven in China served as a divine justification for the emperor's rule, fostering political stability through the belief that natural disasters signaled loss of legitimacy, which deeply influenced social order and governance. In contrast, Japan's sankin-kotai system enforced daimyo attendance in Edo, effectively centralizing power under the shogunate by controlling regional lords and reducing the threat of rebellion. This policy facilitated urban growth, economic integration, and a rigid social hierarchy, significantly shaping Japan's societal structure during the Edo period.

Power, Stability, and Rebellion: Outcomes in China vs. Japan

The Mandate of Heaven in China centralized power by justifying the ruler's divine right and framing rebellion as a sign of lost legitimacy, which maintained stability through cyclical dynastic changes. Sankin-kotai in Japan imposed alternating residence duties on daimyo to the shogun, effectively controlling regional power and reducing insurrections by physical and financial constraints. While China's system legitimized overthrow under failed rule, Japan's sankin-kotai emphasized preemptive control to prevent rebellion, shaping contrasting outcomes in political stability and power dynamics.

Legacy and Modern Perspectives on Mandate of Heaven and Sankin-kōtai

The Mandate of Heaven shaped imperial legitimacy in China by justifying dynastic changes through divine approval, influencing modern political thought on governance and moral authority. Sankin-kotai, a policy of alternate attendance during Japan's Edo period, centralized feudal control and led to economic growth, impacting Japan's modernization and bureaucratic efficiency. Contemporary views recognize the Mandate of Heaven as foundational to Chinese political philosophy, whereas Sankin-kotai is seen as a practical mechanism fostering stability and state formation.

Mandate of Heaven in China Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com