Gallicanism emphasizes the independence of the French Catholic Church from papal authority, advocating for the king's rule over church matters within France. It played a crucial role in shaping the religious and political landscape, balancing royal power and church influence. Explore the rest of the article to understand how Gallicanism impacted both church governance and French history.

Table of Comparison

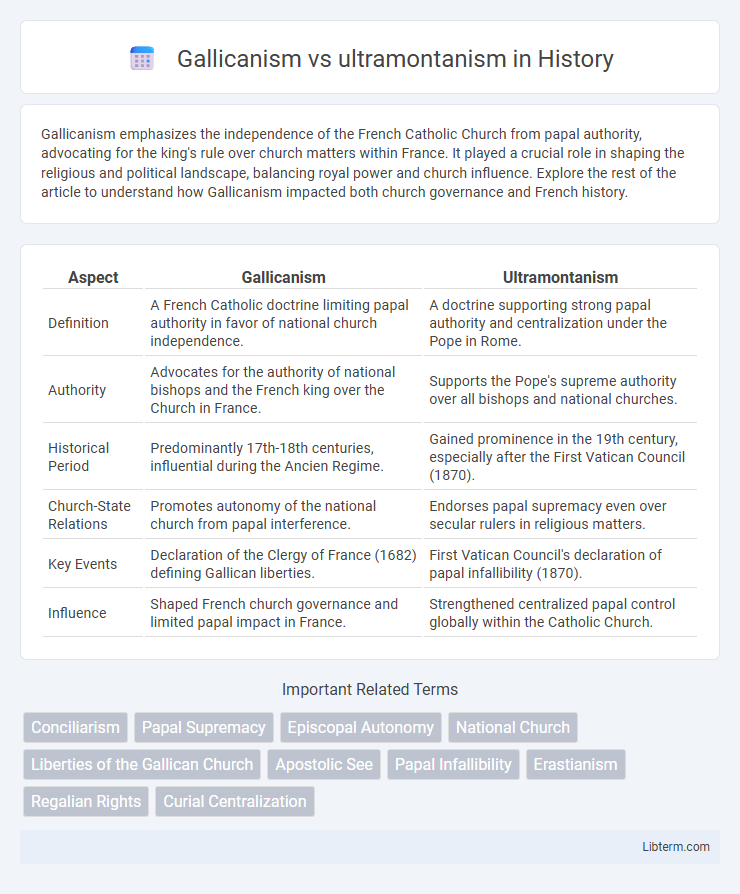

| Aspect | Gallicanism | Ultramontanism |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A French Catholic doctrine limiting papal authority in favor of national church independence. | A doctrine supporting strong papal authority and centralization under the Pope in Rome. |

| Authority | Advocates for the authority of national bishops and the French king over the Church in France. | Supports the Pope's supreme authority over all bishops and national churches. |

| Historical Period | Predominantly 17th-18th centuries, influential during the Ancien Regime. | Gained prominence in the 19th century, especially after the First Vatican Council (1870). |

| Church-State Relations | Promotes autonomy of the national church from papal interference. | Endorses papal supremacy even over secular rulers in religious matters. |

| Key Events | Declaration of the Clergy of France (1682) defining Gallican liberties. | First Vatican Council's declaration of papal infallibility (1870). |

| Influence | Shaped French church governance and limited papal impact in France. | Strengthened centralized papal control globally within the Catholic Church. |

Introduction to Gallicanism and Ultramontanism

Gallicanism advocates for reducing papal authority in favor of national church autonomy, emphasizing the power of local bishops and the French crown in ecclesiastical matters. Ultramontanism supports strong centralized papal authority and the supremacy of the pope over regional churches, particularly reinforcing Rome's influence beyond national boundaries. These contrasting ideologies shaped the political and religious landscape of Europe by influencing church-state relations and ecclesiastical governance during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Historical Origins of Gallicanism

Gallicanism originated in medieval France as a doctrine emphasizing the administrative independence of the French Church from papal authority, rooted in the pragmatic need for national sovereignty over religious matters. This movement gained momentum during the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly under the influence of the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges (1438) and the Declaration of the Clergy of France (1682), which asserted limits on papal power and highlighted the authority of the French monarchy and bishops. The historical tensions between Gallicanism and ultramontanism reflect broader conflicts over church-state relations and centralized ecclesiastical authority.

Development and Principles of Ultramontanism

Ultramontanism developed in the 17th and 18th centuries as a movement emphasizing papal authority and centralized ecclesiastical power, opposing the national church autonomy championed by Gallicanism. Its core principles assert the pope's supreme jurisdiction over the universal Church, including the authority to define doctrine and intervene in local church governance. This doctrine gained significant momentum during the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), which formally defined papal infallibility and reinforced ultramontane supremacy.

Key Differences Between Gallicanism and Ultramontanism

Gallicanism emphasized the independence of the French Church from papal authority, advocating for national church governance and limiting the pope's influence in political and ecclesiastical matters. Ultramontanism, conversely, promoted strong papal supremacy, asserting the pope's ultimate authority over local churches and bishops worldwide. The key difference lies in Gallicanism's support for regional ecclesiastical autonomy versus Ultramontanism's endorsement of centralized papal control.

The Role of the Papacy in Both Movements

Gallicanism emphasized the limitation of papal authority, advocating for the autonomy of national churches and the supremacy of secular rulers in ecclesiastical matters, particularly in France during the 17th and 18th centuries. Ultramontanism championed the centralization of church power in the papacy, asserting the pope's supreme spiritual and doctrinal authority over local bishops and national churches, especially during the 19th century's First Vatican Council. The papacy under Gallicanism was viewed as a powerful yet not absolute figure, whereas ultramontanism positioned the pope as the ultimate and infallible leader of the Catholic Church worldwide.

Political and National Influences on Church Authority

Gallicanism emphasized the independence of the French Church from papal authority, advocating for national control over ecclesiastical matters and reducing the pope's influence in political and administrative affairs. Ultramontanism stressed papal supremacy and centralized church authority under Rome, asserting that the pope's spiritual and political influence extended beyond national boundaries. These conflicting views shaped the balance of power between church and state, influencing legislation, governance, and national identity in countries like France during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Major Figures and Theological Arguments

Major figures in Gallicanism include Cardinal de Retz and Louis XIV, who emphasized the autonomy of the French Church from papal authority, while Ultramontanism was championed by Pope Pius IX and Saint Robert Bellarmine, asserting the centrality of papal supremacy. Theological arguments of Gallicanism prioritize the authority of national councils and monarchs, stressing limited papal jurisdiction, whereas Ultramontanism defends the doctrine of papal infallibility and universal jurisdiction over the Church. These contrasting positions reflect broader conflicts over church-state relations and the scope of papal power in early modern Europe.

Gallicanism and Ultramontanism in Ecumenical Councils

Gallicanism emphasized the independence of national churches and limited papal authority, particularly opposing ultramontanist claims during Ecumenical Councils such as the Council of Trent and the First Vatican Council. Ultramontanism, advocating strong papal supremacy and infallibility, gained significant traction at the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), which defined the doctrine of papal infallibility, directly countering Gallican viewpoints. The tension between Gallicanism and Ultramontanism reflected broader conflicts over church governance, with Gallican delegates seeking to preserve local episcopal authority and autonomy from Rome.

Decline and Legacy in Modern Catholicism

The decline of Gallicanism in the 19th century was marked by the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), which affirmed papal infallibility and centralized ecclesiastical authority, diminishing national church autonomy. Ultramontanism's legacy persists in modern Catholicism through reinforced papal primacy and doctrinal unity, influencing Vatican II reforms and global church governance. The tension between local episcopal authority and papal centralization continues to shape debates on church authority and Catholic identity worldwide.

Contemporary Perspectives on Church Authority

Contemporary perspectives on church authority reflect an ongoing tension between Gallicanism, which advocates for national churches' autonomy and limits papal influence, and ultramontanism, emphasizing the pope's supreme authority over the universal Church. In modern theological discourse, ultramontanism often aligns with centralized ecclesiastical governance, as seen in the Vatican's role in issuing definitive doctrinal statements. Gallican ideas persist in some regional Catholic communities, promoting localized decision-making and contextual adaptation of church teachings within broader canonical frameworks.

Gallicanism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com