Foundherentism integrates the strengths of foundationalism and coherentism to create a robust theory of justification, emphasizing both basic beliefs and their coherence within a system. This approach addresses classical epistemological challenges by allowing foundational beliefs to support each other in a web-like structure, avoiding issues of infinite regress or circularity. Discover how foundherentism can deepen your understanding of knowledge by exploring the detailed explanation in the rest of this article.

Table of Comparison

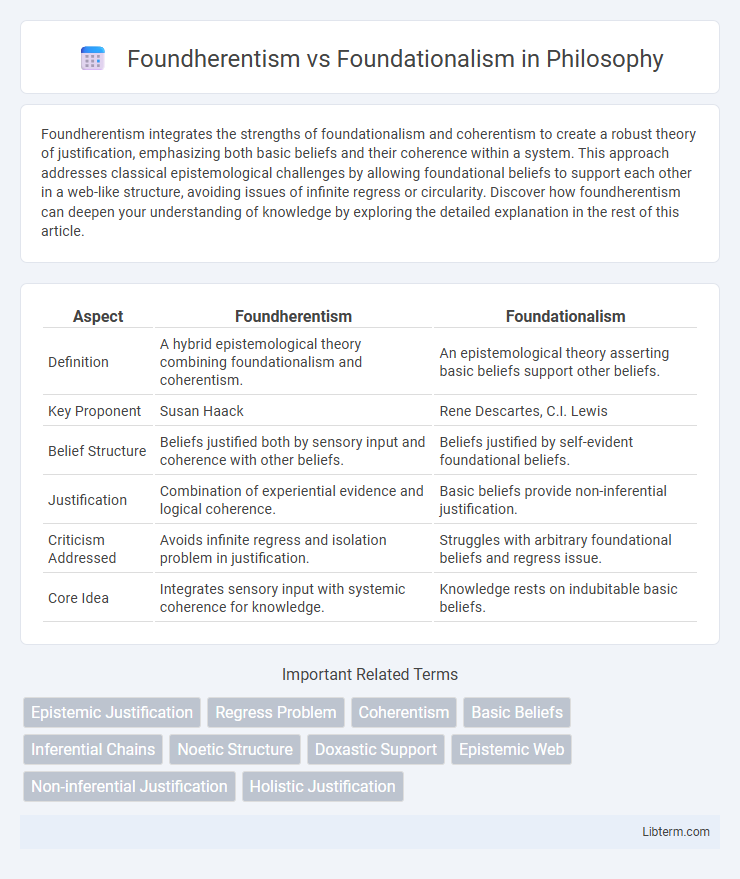

| Aspect | Foundherentism | Foundationalism |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A hybrid epistemological theory combining foundationalism and coherentism. | An epistemological theory asserting basic beliefs support other beliefs. |

| Key Proponent | Susan Haack | Rene Descartes, C.I. Lewis |

| Belief Structure | Beliefs justified both by sensory input and coherence with other beliefs. | Beliefs justified by self-evident foundational beliefs. |

| Justification | Combination of experiential evidence and logical coherence. | Basic beliefs provide non-inferential justification. |

| Criticism Addressed | Avoids infinite regress and isolation problem in justification. | Struggles with arbitrary foundational beliefs and regress issue. |

| Core Idea | Integrates sensory input with systemic coherence for knowledge. | Knowledge rests on indubitable basic beliefs. |

Introduction to Epistemological Theories

Foundherentism integrates elements of foundationalism and coherentism by proposing that beliefs are justified through a dynamic interplay of both foundational evidence and coherence within a belief system. Foundationalism asserts that knowledge rests on basic, self-evident beliefs that provide a secure foundation for further knowledge. These epistemological theories address the structure of justification, where foundherentism seeks to overcome foundationalism's rigidity by allowing for mutual support among beliefs while maintaining objective grounding.

Defining Foundherentism

Foundherentism combines elements of foundationalism and coherentism by proposing that justification is both supported by basic beliefs and derived from the coherence among beliefs within a system. Unlike strict foundationalism, which emphasizes indubitable basic beliefs as a secure base, foundherentism allows for mutual support between beliefs, creating a more flexible epistemic structure. This theory, developed by Susan Haack, addresses challenges in traditional epistemology by integrating evidential support and network coherence.

Core Principles of Foundationalism

Foundationalism asserts that knowledge is structured like a building, resting on indubitable basic beliefs or axioms that serve as the foundation for all other derived beliefs. These foundational beliefs are self-evident, infallible, or evident to the senses, providing a secure base to prevent the infinite regress problem in epistemology. The core principle emphasizes that non-foundational beliefs gain their justification solely through their connection to these foundational beliefs, ensuring a clear epistemic hierarchy.

Historical Background and Key Philosophers

Foundherentism emerged as a modern epistemological theory attempting to reconcile the strengths of foundationalism and coherentism, with Susan Haack as a principal advocate in the late 20th century. Foundationalism, rooted in ancient philosophy, notably developed through Descartes and later Locke and Reid, asserts that knowledge derives from basic, self-evident beliefs or sensory experiences. Key philosophers in foundationalism include Rene Descartes, who emphasized indubitable foundations, while Haack challenged both foundationalism and coherentism, proposing a hybrid "foundherent" approach to justify beliefs through both foundational elements and coherence within a web of beliefs.

Core Differences: Foundherentism vs Foundationalism

Foundherentism combines elements of foundationalism and coherentism by allowing beliefs to be justified through both foundational support and coherence within a belief system, challenging the rigid structure of foundationalism that relies solely on basic, self-evident beliefs. Foundationalism asserts that all knowledge or justified belief rests on a foundation of indubitable, non-inferential beliefs, emphasizing a linear justification model. The core difference lies in foundherentism's rejection of the strict hierarchy of justification, promoting a more flexible, integrated approach to epistemic support.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Foundationalism

Foundationalism offers a clear structure for knowledge by asserting that beliefs rest on basic, self-evident truths, providing a solid epistemic foundation. Its strength lies in preventing infinite regress by establishing indubitable premises, yet it faces challenges such as identifying truly basic beliefs and justifying how complex knowledge reliably derives from them. Critics argue that foundationalism may oversimplify the intricate nature of justification, potentially overlooking the interconnectedness emphasized in alternative theories like coherentism.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Foundherentism

Foundherentism combines the strengths of foundationalism and coherentism by offering a flexible justification framework that supports both basic beliefs and web-like coherence among beliefs, which enhances its ability to address epistemic regress problems. However, its complexity can lead to difficulties in clearly delineating which beliefs should serve as foundations versus those justified coherently, potentially weakening its explanatory power. The hybrid nature empowers a more realistic epistemic evaluation by accommodating diverse types of justification but may struggle with ambiguity in practical application and theoretical clarity.

Practical Implications in Knowledge Acquisition

Foundherentism integrates coherentist and foundationalist elements, allowing for more flexible knowledge acquisition by combining basic beliefs supported by experiential evidence with a web of justificatory relations. Foundationalism emphasizes a strict hierarchy where knowledge builds upon indubitable foundational beliefs, often resulting in rigid criteria for practical decision-making and learning processes. The practical implication is that foundherentism facilitates adaptive and context-sensitive reasoning in acquiring knowledge, while foundationalism prioritizes certainty and clarity but may limit responsiveness to new information.

Contemporary Debates and Criticisms

Contemporary debates in epistemology contrast foundherentism's hybrid approach, combining coherentism and foundationalism, with traditional foundationalism's strict hierarchical structure of knowledge justification. Critics of foundherentism argue it risks circularity and lacks clear criteria for foundational beliefs, while foundationalism faces challenges in explaining how basic beliefs are epistemically justified without infinite regress. Recent discussions emphasize foundherentism's flexibility in addressing these issues, yet foundationalists defend the clarity and simplicity of their epistemic framework.

Conclusion: The Future of Epistemological Inquiry

Foundherentism integrates the strengths of foundationalism and coherentism, offering a flexible framework that addresses limitations in traditional epistemological models. This hybrid approach encourages deeper exploration of knowledge justification by blending empirical evidence with coherent belief systems. Future epistemological inquiry will likely benefit from Foundherentism's dynamic synthesis, promoting more nuanced understanding and adaptive theories in the philosophy of knowledge.

Foundherentism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com