Essential knowledge empowers you to tackle challenges effectively and make informed decisions in various aspects of life. Developing necessary skills and understanding fosters personal growth and professional success. Explore the rest of this article to uncover key strategies for mastering what is truly necessary.

Table of Comparison

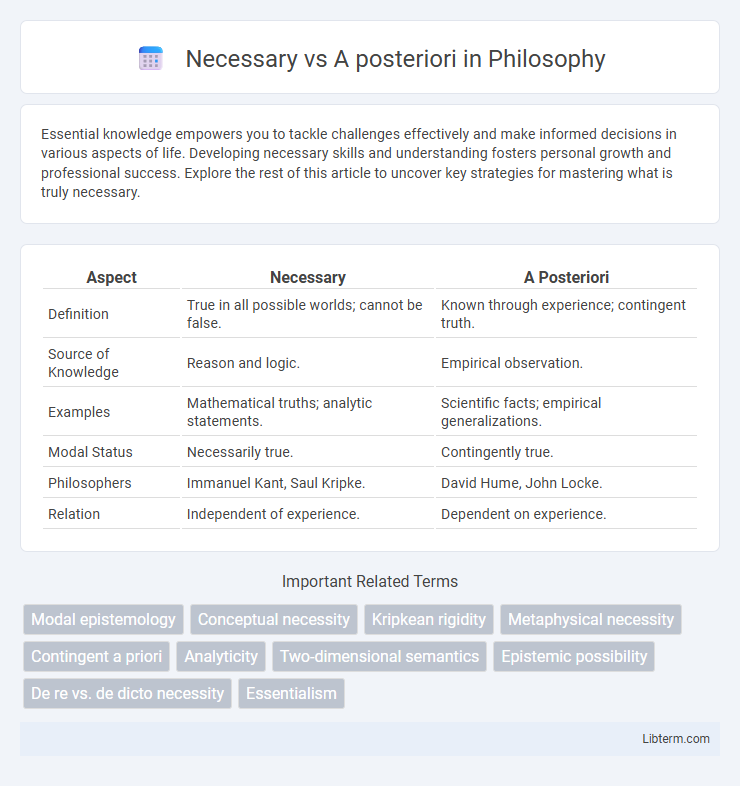

| Aspect | Necessary | A Posteriori |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | True in all possible worlds; cannot be false. | Known through experience; contingent truth. |

| Source of Knowledge | Reason and logic. | Empirical observation. |

| Examples | Mathematical truths; analytic statements. | Scientific facts; empirical generalizations. |

| Modal Status | Necessarily true. | Contingently true. |

| Philosophers | Immanuel Kant, Saul Kripke. | David Hume, John Locke. |

| Relation | Independent of experience. | Dependent on experience. |

Defining "Necessary" Truths

Necessary truths are propositions that cannot be false under any possible circumstances, such as mathematical statements like "2+2=4," reflecting their inherent logical necessity. These truths hold across all possible worlds, distinguishing them from contingent truths, which depend on empirical facts and may vary. The a posteriori dimension involves knowledge gained through experience, whereas necessary truths are typically known a priori, independent of sensory input.

Explaining "A Posteriori" Knowledge

A posteriori knowledge is understanding gained through empirical experience and observation, relying on sensory input to confirm facts. It contrasts with a priori knowledge, which is known independently of experience, such as mathematical truths. Examples of a posteriori knowledge include scientific discoveries and everyday learning, where evidence and experimentation validate the truth.

Historical Context: Philosophers on Necessity and A Posteriori

Philosophers like Immanuel Kant revolutionized the understanding of necessity and a posteriori knowledge by introducing the concept of synthetic a priori judgments, challenging the strict distinction between analytic a priori and synthetic a posteriori knowledge prevalent in the Enlightenment. Earlier thinkers such as David Hume emphasized the empirical basis of a posteriori knowledge, arguing that necessity is not derived from experience but a product of the mind's habits. This historical evolution reflects a complex dialogue on how necessity is conceptualized relative to experience, shaping contemporary epistemology and metaphysics.

The Distinction: Necessary vs. Contingent Statements

Necessary statements are true in all possible worlds and cannot be false, such as mathematical truths or logical tautologies. Contingent statements are true in some possible worlds and false in others, depending on empirical facts or conditions that could have been otherwise. The distinction highlights the difference between a priori knowledge, which is independent of experience, and a posteriori knowledge, which relies on empirical evidence.

Examples of Necessary Truths

Mathematical statements such as "2 + 2 = 4" exemplify necessary truths, holding true in all possible worlds without exception. Logical tautologies like "All bachelors are unmarried" cannot be false, as their truth derives from the meanings of the terms involved. Contrastingly, a posteriori truths rely on empirical evidence, making necessary truths foundational in analytic philosophy and modal logic.

Examples of A Posteriori Knowledge

A posteriori knowledge is derived from empirical evidence and sensory experience, such as knowing that water boils at 100degC based on observation. Scientific facts like the Earth orbiting the Sun or the boiling point of substances exemplify a posteriori knowledge, as they require confirmation through experimentation and observation. Everyday experiences, like recognizing fire causes heat or tasting sweetness in sugar, further illustrate the dependency of a posteriori knowledge on direct sensory input.

Can Necessary Truths Be Known A Posteriori?

Necessary truths are traditionally understood as those that hold in all possible worlds and can be known a priori, independent of experience. However, some philosophers argue that certain necessary truths, such as "Water is H2O," can be known a posteriori through empirical investigation and scientific discovery. This challenges the strict division between necessary truths being a priori and contingent truths being a posteriori, suggesting that knowledge of necessity can sometimes arise from sensory experience.

Kripke's Contributions: Naming and Necessity

Saul Kripke revolutionized modal logic and philosophy of language through his work "Naming and Necessity," distinguishing necessary truths from a posteriori knowledge. He argued that some statements, such as "Water is H2O," are necessarily true yet knowable only through empirical investigation, challenging traditional epistemological categories. Kripke introduced the concept of rigid designators, which refer to the same entity in all possible worlds, underscoring the semantic importance of necessity in language and metaphysics.

Philosophical Debates on Necessity and Experience

Philosophical debates on necessity and experience center on distinguishing necessary truths, which hold in all possible worlds, from a posteriori knowledge derived from empirical evidence. Necessary propositions, such as mathematical truths, are considered immutable and independent of sensory input, while a posteriori statements depend on observation and contingency. This distinction fuels ongoing discussions about the limits of human knowledge, the nature of metaphysical necessity, and the role of experience in validating truth claims.

Implications for Epistemology and Metaphysics

Necessary truths, such as mathematical statements, hold true in all possible worlds and provide a foundation for certain knowledge, impacting epistemology by defining the limits of what can be known a priori. A posteriori knowledge relies on empirical observation and affects metaphysics by grounding our understanding of contingent facts and the actual state of the world. The distinction shapes debates on the nature of knowledge, truth, and reality, highlighting how necessity and contingency influence epistemic justification and metaphysical explanation.

Necessary Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com