Analytic a priori knowledge refers to truths that are inherently known without needing empirical evidence, such as definitions or logical deductions. These statements are true by virtue of their meaning and are necessarily valid, independent of sensory experience. Explore the rest of the article to deepen your understanding of the significance and application of analytic a priori knowledge in philosophy.

Table of Comparison

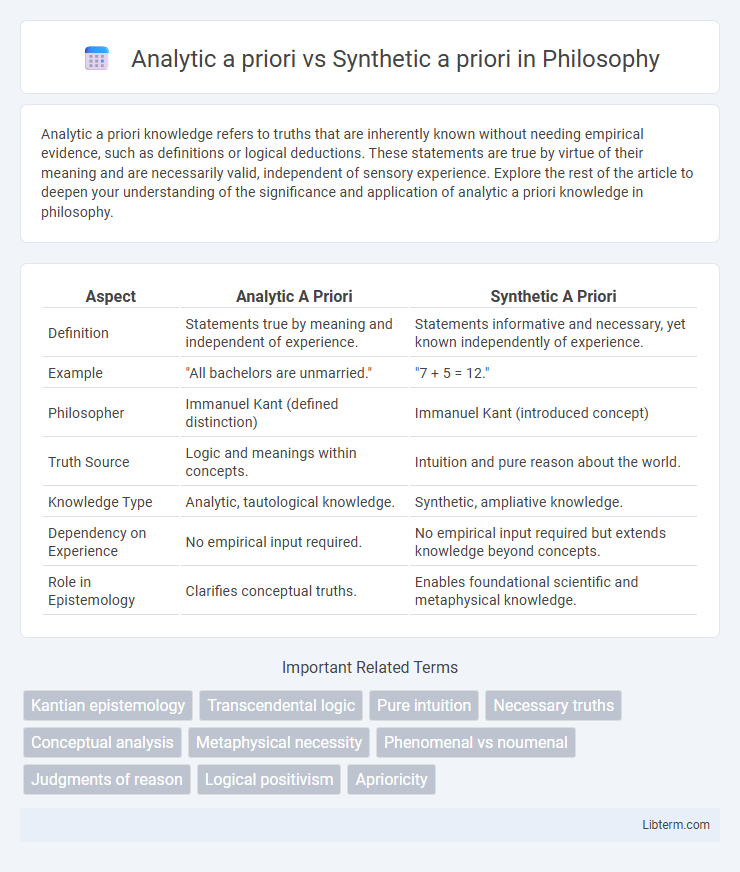

| Aspect | Analytic A Priori | Synthetic A Priori |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Statements true by meaning and independent of experience. | Statements informative and necessary, yet known independently of experience. |

| Example | "All bachelors are unmarried." | "7 + 5 = 12." |

| Philosopher | Immanuel Kant (defined distinction) | Immanuel Kant (introduced concept) |

| Truth Source | Logic and meanings within concepts. | Intuition and pure reason about the world. |

| Knowledge Type | Analytic, tautological knowledge. | Synthetic, ampliative knowledge. |

| Dependency on Experience | No empirical input required. | No empirical input required but extends knowledge beyond concepts. |

| Role in Epistemology | Clarifies conceptual truths. | Enables foundational scientific and metaphysical knowledge. |

Introduction to Analytic and Synthetic Judgments

Analytic judgments are statements true by virtue of their meaning, where the predicate concept is contained within the subject concept, such as "All bachelors are unmarried." Synthetic judgments, in contrast, add new information by connecting the predicate to the subject in a way not contained within its definition, exemplified by "The cat is on the mat." The distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments underpins key debates in epistemology, particularly in Kantian philosophy, differentiating knowledge based on conceptual analysis from knowledge informed by experience or intuition.

Defining Analytic A Priori Knowledge

Analytic a priori knowledge consists of statements true by definition, where the predicate is contained within the subject, exemplified by propositions like "All bachelors are unmarried." These truths do not rely on empirical evidence and are justified solely through logical analysis and understanding of language. This contrasts with synthetic a priori knowledge, which extends beyond definitions and requires rational intuition or insight.

Understanding Synthetic A Priori Knowledge

Synthetic a priori knowledge combines empirical content with necessary truth, allowing for insights that extend beyond mere definitions without relying solely on experience. Immanuel Kant identified synthetic a priori judgments as crucial for foundational principles in mathematics and natural sciences, exemplified by statements such as "7 + 5 = 12" and the concept of causality. This type of knowledge bridges the gap between analytic truths and empirical observations, structuring human cognition and scientific understanding through universal yet informative propositions.

Historical Background: Kant's Contribution

Immanuel Kant revolutionized epistemology by distinguishing analytic a priori judgments, which are true by definition and independent of experience, from synthetic a priori judgments, which expand knowledge yet remain universally valid without empirical proof. Before Kant, the prevailing view separated knowledge into analytic truths, based on logic and definitions, and synthetic truths, grounded in experience. Kant introduced the synthetic a priori category to explain how fundamental principles of mathematics and natural science possess necessary truth while being informed by the structure of human cognition.

Key Differences Between Analytic and Synthetic A Priori

Analytic a priori judgments are true by virtue of their meaning and logical form, such as "All bachelors are unmarried," where the predicate is contained within the subject. Synthetic a priori judgments, like "7 + 5 = 12," add new information that is not contained in the subject but are known independently of experience. The key difference lies in analytic a priori relying on analytic truth based on definition, while synthetic a priori involves substantial knowledge that extends beyond mere logical analysis yet remains necessarily true prior to empirical input.

Classic Examples of Analytic A Priori Propositions

Classic examples of analytic a priori propositions include mathematical truths such as "All bachelors are unmarried" and logical statements like "A triangle has three sides." These propositions are true by virtue of their meaning and do not require empirical verification, as their predicates are contained within their subjects. Kant's philosophy highlights these as foundational to understanding knowledge that is necessarily true and known independently of experience.

Illustrative Cases of Synthetic A Priori Propositions

Synthetic a priori propositions are exemplified by mathematical judgments such as "7 + 5 = 12," which are not true by definition yet known independently of experience. Another illustrative case is Kant's statement "Every event has a cause," reflecting necessary knowledge extending beyond mere analysis of concepts. These examples demonstrate that synthetic a priori knowledge combines informativeness with a priori certainty, distinguishing it from analytic propositions.

Philosophical Debates and Criticisms

Analytic a priori judgments, defined by their inherent truth through meanings and logical analysis, face criticism for limiting knowledge to tautologies and tautological statements. Synthetic a priori knowledge, which Kant argues combines necessity with empirical content, is debated for its seemingly contradictory nature, as critics question how synthetic knowledge can be known independently of experience. Philosophical debates center on the validity, scope, and epistemic foundations of these categories, with post-Kantian philosophers challenging Kant's strict separation and proposing more nuanced understandings of analytical and synthetic distinctions.

Relevance in Contemporary Epistemology

Analytic a priori judgments are true by virtue of meanings and logical relations, exemplified by statements like "All bachelors are unmarried," while synthetic a priori judgments extend knowledge by connecting concepts beyond mere definitions, such as "7 + 5 = 12." Contemporary epistemology investigates their relevance by assessing how synthetic a priori knowledge underpins fundamental principles in mathematics, ethics, and natural sciences, challenging purely empirical or analytic frameworks. This distinction informs debates on the sources of knowledge, justifying non-empirical truths critical for understanding cognitive structures and epistemic justification.

Implications for Logic and Metaphysics

Analytic a priori judgments, exemplified by statements like "All bachelors are unmarried," are true by definition and hold significance for formal logic through their reliance on tautologies and conceptual necessity. Synthetic a priori judgments, such as Kant's assertion that "7 + 5 = 12," provide substantive knowledge about the world independent of experience, influencing metaphysical claims about the nature of space, time, and causality. These distinctions impact the foundations of logic by delineating necessary truths from empirical synthesis and shape metaphysics by grounding transcendent truths beyond sensory experience.

Analytic a priori Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com