Jonang is a unique school of Tibetan Buddhism known for its distinct philosophy emphasizing the concept of "shentong" or empty-of-other, which contrasts with the mainstream "rangtong" view. It also preserves ancient tantric teachings and has a rich history marked by periods of suppression and revival, particularly in regions like Amdo. Explore the rest of this article to understand how Jonang's teachings and practices can deepen Your appreciation of Tibetan Buddhist traditions.

Table of Comparison

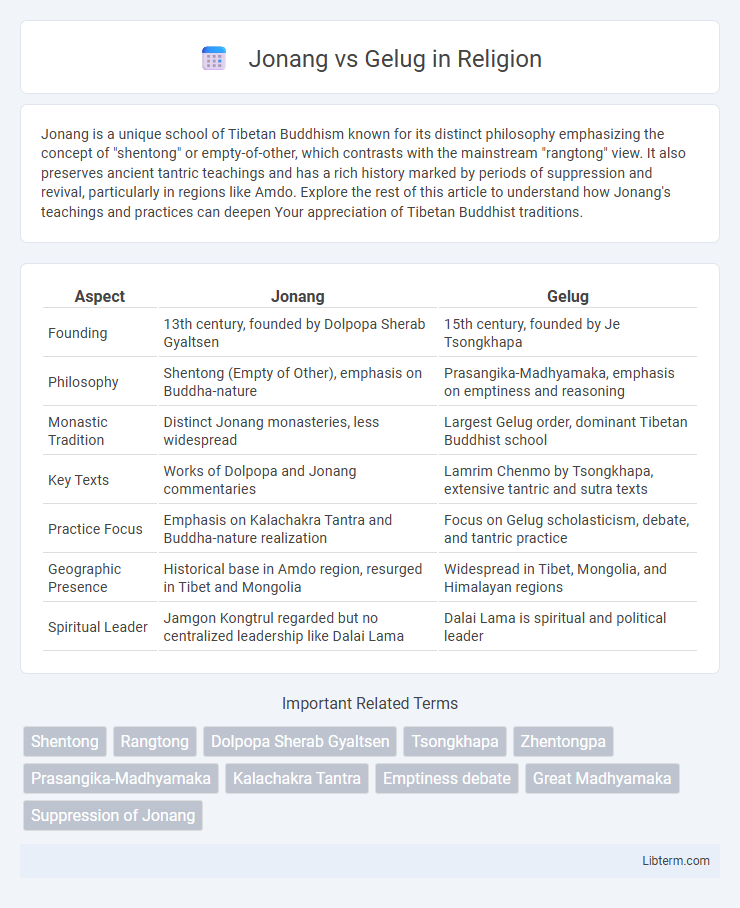

| Aspect | Jonang | Gelug |

|---|---|---|

| Founding | 13th century, founded by Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen | 15th century, founded by Je Tsongkhapa |

| Philosophy | Shentong (Empty of Other), emphasis on Buddha-nature | Prasangika-Madhyamaka, emphasis on emptiness and reasoning |

| Monastic Tradition | Distinct Jonang monasteries, less widespread | Largest Gelug order, dominant Tibetan Buddhist school |

| Key Texts | Works of Dolpopa and Jonang commentaries | Lamrim Chenmo by Tsongkhapa, extensive tantric and sutra texts |

| Practice Focus | Emphasis on Kalachakra Tantra and Buddha-nature realization | Focus on Gelug scholasticism, debate, and tantric practice |

| Geographic Presence | Historical base in Amdo region, resurged in Tibet and Mongolia | Widespread in Tibet, Mongolia, and Himalayan regions |

| Spiritual Leader | Jamgon Kongtrul regarded but no centralized leadership like Dalai Lama | Dalai Lama is spiritual and political leader |

Historical Origins of Jonang and Gelug Schools

The Jonang school originated in the 13th century, founded by Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, emphasizing the unique philosophical concept of Shentong, which distinguishes it from other Tibetan Buddhist traditions. The Gelug school, established by Je Tsongkhapa in the late 14th century, is renowned for its strict monastic discipline and the prominence of the Dalai Lama lineage. Historically, the Gelug school gained political dominance in Tibet, especially from the 17th century onwards, while the Jonang school faced suppression but has experienced a revival in modern times.

Founding Figures: Dolpopa vs. Tsongkhapa

Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, the founding figure of the Jonang tradition, emphasized the philosophy of "Shentong," which interprets emptiness as the absence of other, highlighting the intrinsic nature of ultimate reality. Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelug school, systematized Madhyamaka philosophy with a strong focus on rigorous scholasticism and ethical discipline, advocating for Prasangika Madhyamaka as the definitive view. The contrasting foundations laid by Dolpopa's emphasis on Buddha-nature and Tsongkhapa's analytical reasoning illustrate the philosophical divergence between Jonang and Gelug traditions.

Core Philosophical Differences

The Jonang school emphasizes the shentong view of emptiness, asserting that ultimate reality is an intrinsically existing, luminous Buddha-nature beyond conventional emptiness, while the Gelug tradition upholds the rangtong perspective, which contends that all phenomena, including emptiness itself, lack inherent existence. Jonang's philosophical stance centers on the affirming the presence of an absolute, non-dual reality, contrasting with Gelug's rigorous Madhyamaka approach that negates inherent nature to avoid reification. These divergent interpretations of emptiness shape distinct meditation practices and doctrinal teachings fundamental to each lineage.

The Jonang Emphasis on Shentong Philosophy

The Jonang school emphasizes the Shentong philosophy, which asserts that ultimate reality is empty of other but inherently possesses luminous qualities and Buddha-nature, contrasting with the Gelug school's Rangtong view that all phenomena, including ultimate reality, are empty of inherent existence. Jonang scholars argue that Shentong reveals the transcendental wisdom of the Buddha's mind, focusing on the positive nature of emptiness as an eternal, dynamic presence. This philosophical distinction underpins doctrinal debates and influences distinct meditation practices within Tibetan Buddhism.

Gelug's Prasangika Madhyamaka Approach

The Gelug school, founded by Je Tsongkhapa, emphasizes the Prasangika Madhyamaka approach, which advocates a rigorous dialectical method to deconstruct inherent existence through reductio ad absurdum reasoning. Contrasting with the Jonang school's focus on the Shentong interpretation of emptiness, Gelug Prasangika Madhyamaka maintains that all phenomena lack intrinsic nature, rejecting any form of ultimate substance or essence. This philosophical distinction underpins Gelug scholasticism and monastic debate traditions, prioritizing logic and epistemology to attain the realization of emptiness and achieve liberation.

Monastic Practices and Rituals Compared

The Jonang school emphasizes unique monastic practices centered on the zhentong view of emptiness and the extensive use of the Kalachakra tantra, which influences their ritual forms and meditation techniques. In contrast, the Gelug tradition prioritizes strict monastic discipline, scholastic study, and debate, with rituals often focused on Lamrim teachings and tantric initiations aligned with Tsongkhapa's reforms. These differences reflect Jonang's distinct doctrinal focus and ritual expression compared to Gelug's standardized monastic codes and educational system.

Political Influence and Historical Suppression

The Jonang school faced systematic political suppression by the dominant Gelug sect during the 17th century, particularly under the rule of the Fifth Dalai Lama, who sought to consolidate political power in Tibet. The Gelugpa's alliance with the Mongol forces allowed them to dismantle Jonang monasteries, ban their teachings, and reclassify Jonang texts as heretical, drastically reducing their influence. Despite this historical suppression, the Jonang tradition has experienced a revival in recent decades, reclaiming its unique philosophical contributions and political identity within Tibetan Buddhism.

Revival Efforts and Modern Presence

The Jonang tradition, once suppressed and absorbed by the Gelug school in the 17th century, has experienced significant revival efforts since the late 20th century, particularly in regions of Tibet and Mongolia. Modern Jonang centers emphasize the preservation of their unique philosophical teachings, such as the shentong view of emptiness, which contrasts with the Gelug's prasangika interpretation rooted in Tsongkhapa's philosophy. Despite Gelug's predominant global presence through institutions like Ganden Monastery and the Dalai Lama's leadership, the Jonang revival has fostered renewed scholarship, translation projects, and monastic communities, contributing to a pluralistic Buddhist landscape today.

Key Texts and Doctrinal Literature

Jonang and Gelug traditions diverge significantly in their key texts and doctrinal literature, with Jonang emphasizing the *Shentong* interpretation of emptiness primarily based on the *Kamalashila's* *Madhyamakavyakhya* and *Tathagatagarbha* sutras. Gelug scholars focus on the works of Tsongkhapa, such as the *Lamrim Chenmo* and commentaries on *Nagarjuna's* *Mulamadhyamakakarika*, emphasizing *Rangtong* emptiness. The textual corpus in Jonang highlights a unique ontological framework of ultimate reality, contrasting with the Gelug systematic scholasticism that reinforces strict analytical meditation practices.

The Legacy and Future of Jonang and Gelug Traditions

The Jonang tradition preserves unique teachings on sunyata and the Tathagatagarbha, maintaining distinct philosophical perspectives despite historical suppression by the Gelug school. Gelug, known for its scholastic rigor and emphasis on monastic discipline, dominates Tibetan Buddhism but faces modern challenges of globalization and modernization. Both traditions contribute to Buddhism's future by fostering revival efforts and engaging in inter-sect dialogue, ensuring the preservation and evolution of their rich spiritual legacies.

Jonang Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com