Atonement involves making amends for wrongdoing or seeking forgiveness to restore harmony and personal integrity. Understanding the psychological and spiritual aspects of atonement can transform how you address guilt and repair relationships. Discover the deeper meaning and practical steps of atonement by reading the rest of this article.

Table of Comparison

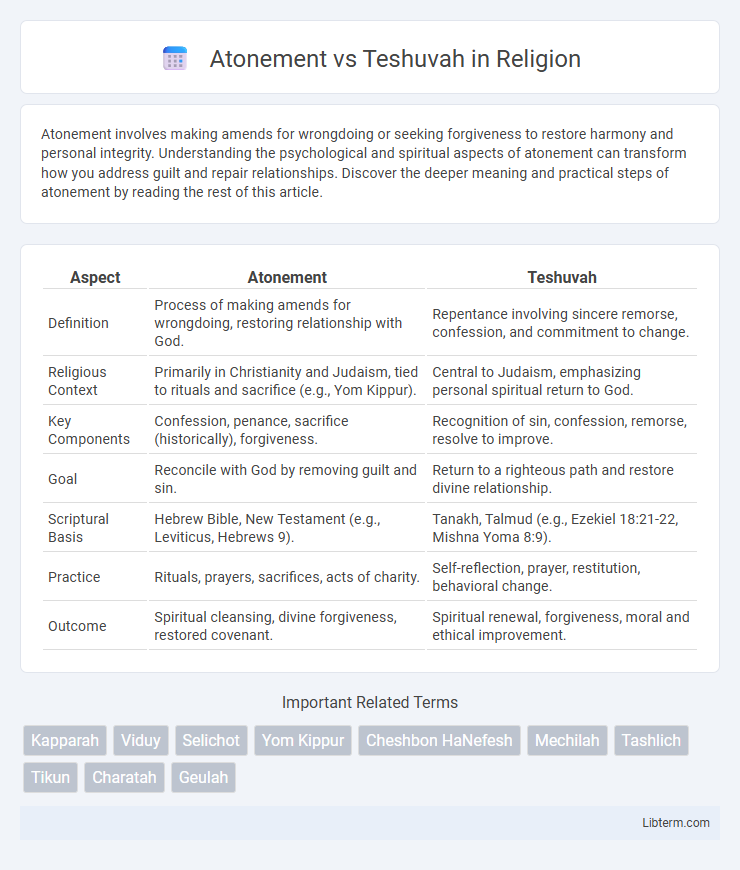

| Aspect | Atonement | Teshuvah |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Process of making amends for wrongdoing, restoring relationship with God. | Repentance involving sincere remorse, confession, and commitment to change. |

| Religious Context | Primarily in Christianity and Judaism, tied to rituals and sacrifice (e.g., Yom Kippur). | Central to Judaism, emphasizing personal spiritual return to God. |

| Key Components | Confession, penance, sacrifice (historically), forgiveness. | Recognition of sin, confession, remorse, resolve to improve. |

| Goal | Reconcile with God by removing guilt and sin. | Return to a righteous path and restore divine relationship. |

| Scriptural Basis | Hebrew Bible, New Testament (e.g., Leviticus, Hebrews 9). | Tanakh, Talmud (e.g., Ezekiel 18:21-22, Mishna Yoma 8:9). |

| Practice | Rituals, prayers, sacrifices, acts of charity. | Self-reflection, prayer, restitution, behavioral change. |

| Outcome | Spiritual cleansing, divine forgiveness, restored covenant. | Spiritual renewal, forgiveness, moral and ethical improvement. |

Understanding Atonement: Key Concepts

Atonement involves repairing the spiritual breach caused by wrongdoing through actions that restore a relationship with the divine, emphasizing reparation and moral accountability. Central to atonement is the concept of sacrifice or reparative acts, symbolizing repentance and purification. Teshuvah, often translated as repentance, focuses on sincere remorse, confession, and a firm commitment to change, highlighting a personal transformation and return to righteousness.

Defining Teshuvah in Jewish Thought

Teshuvah in Jewish thought is the profound process of repentance involving sincere regret for wrongdoing, cessation of the harmful act, and commitment to moral improvement. It encompasses both personal transformation and restoration of one's relationship with God and the community. Distinct from atonement, which often requires ritual acts, teshuvah emphasizes internal change and ethical responsibility as the core of spiritual reconciliation.

Historical Origins of Atonement and Teshuvah

Atonement has roots in ancient sacrificial systems, particularly within the biblical Temple rituals where sin offerings were made to reconcile humans with God, representing a formal, ritualistic forgiveness process. Teshuvah, originating in early rabbinic literature, emphasizes a personal, introspective return to God through repentance, moral reflection, and behavioral change rather than external rituals. While atonement historically involved priestly mediation and physical sacrifices, teshuvah centers on internal transformation and direct accountability in Jewish ethical and spiritual practice.

Scriptural Foundations: Biblical References

Atonement in the Bible primarily refers to the concept of "kippur," as seen in Leviticus 16, where the High Priest performs rituals on Yom Kippur to cover the sins of Israel, emphasizing sacrificial atonement. Teshuvah, meaning "return" or repentance, is rooted in passages like Ezekiel 18:30-32 and Deuteronomy 30:2-3, highlighting personal transformation and the turning away from sin toward God. While atonement involves divine forgiveness through ritual means, teshuvah stresses sincere repentance and ethical renewal as foundational for restoration in the biblical narrative.

Theological Differences: Atonement vs Teshuvah

Atonement in theological terms often involves a process of reconciliation through rituals, sacrifices, or divine intervention to address sin and restore holiness. Teshuvah, a central concept in Judaism, emphasizes sincere repentance, self-reflection, and a personal commitment to change one's behavior as a direct path to forgiveness and spiritual renewal. While atonement may rely on external rites, teshuvah fundamentally requires internal transformation and accountability for moral actions.

Ritual Practices and Symbolism

Atonement in various religious traditions often involves specific ritual practices such as sacrificial offerings, fasting, or prayer ceremonies designed to cleanse sin and restore divine favor. Teshuvah, central to Jewish tradition, emphasizes introspection, confession, and repentance over ritual acts, with symbolic gestures like wearing a kittel or blowing the shofar during Yom Kippur representing spiritual renewal and return to God. Both practices use symbolism to convey purification and reconciliation but differ in method, with atonement frequently external and ritualistic, while teshuvah centers on internal transformation and ethical commitment.

Personal Responsibility and Divine Forgiveness

Atonement involves accepting personal responsibility by recognizing wrongdoing and making reparations to heal relationships, emphasizing active steps toward moral restoration. Teshuvah centers on sincere repentance and turning away from sin, seeking divine forgiveness through heartfelt remorse, confession, and commitment to change. Both concepts highlight the interplay between human accountability and God's mercy in the process of spiritual redemption.

Modern Interpretations and Applications

Modern interpretations of atonement and teshuvah emphasize personal accountability and emotional transformation over ritual compliance, integrating psychological insights to foster genuine remorse and behavioral change. Contemporary applications highlight teshuvah as an ongoing process of self-improvement and ethical realignment, while atonement is viewed through a relational lens, promoting reconciliation with others and social justice. These frameworks reshape traditional concepts to address current ethical challenges and communal healing in diverse, secular, and interfaith contexts.

Comparative Analysis: Impact on Daily Life

Atonement (Kapparah) and Teshuvah both play crucial roles in Jewish spiritual practice, with Teshuvah emphasizing personal reflection, repentance, and behavioral change, directly influencing daily ethical decisions and interpersonal relationships. In contrast, Atonement often involves ritual acts such as prayer, fasting, or charitable deeds, which serve to mend one's relationship with God and community, providing structured opportunities for spiritual renewal. Together, they create a dynamic process where Teshuvah drives ongoing moral development while Atonement offers formal mechanisms for forgiveness and restoration, collectively shaping daily life and spiritual growth.

Embracing Spiritual Growth through Reconciliation

Atonement and Teshuvah both center on embracing spiritual growth through reconciliation by fostering self-reflection, repentance, and transformation. Teshuvah, a Hebrew term meaning "return," highlights the process of turning back to ethical living and divine connection, while atonement emphasizes making amends and restoring harmony. Together, these concepts deepen personal accountability and encourage continuous spiritual renewal within Jewish tradition.

Atonement Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com