The Russian serfdom system was a rigid socio-economic structure that bound peasants to the land owned by nobles, severely limiting their freedom and economic mobility. This system persisted from the 17th century until its abolition in 1861, shaping the country's agrarian economy and social hierarchy. Discover how serfdom influenced Russian history and its lasting impact on society by reading the rest of the article.

Table of Comparison

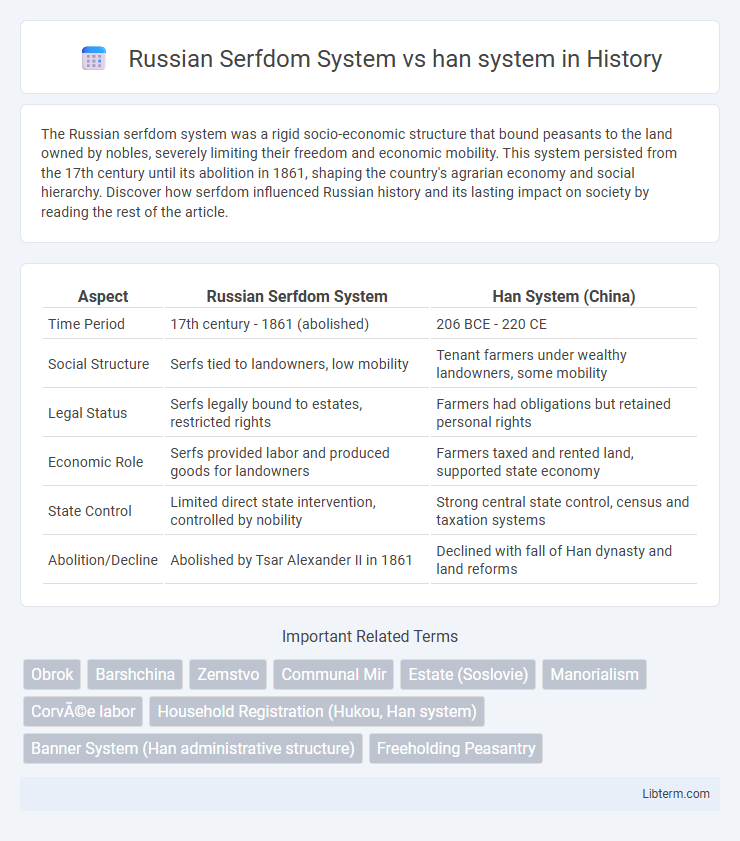

| Aspect | Russian Serfdom System | Han System (China) |

|---|---|---|

| Time Period | 17th century - 1861 (abolished) | 206 BCE - 220 CE |

| Social Structure | Serfs tied to landowners, low mobility | Tenant farmers under wealthy landowners, some mobility |

| Legal Status | Serfs legally bound to estates, restricted rights | Farmers had obligations but retained personal rights |

| Economic Role | Serfs provided labor and produced goods for landowners | Farmers taxed and rented land, supported state economy |

| State Control | Limited direct state intervention, controlled by nobility | Strong central state control, census and taxation systems |

| Abolition/Decline | Abolished by Tsar Alexander II in 1861 | Declined with fall of Han dynasty and land reforms |

Overview of Russian Serfdom and the Han System

Russian serfdom, established in the 16th century, bound peasants to landowners, limiting their freedom and subjecting them to labor obligations and taxes under the feudal hierarchy. The Han System, used in East Asia notably in Chinese bureaucracy, was a state administrative framework emphasizing centralized control, meritocratic governance, and Confucian social order rather than hereditary servitude. While Russian serfdom was primarily an agrarian labor system controlling peasant lives, the Han System structured political authority and social relations through institutionalized civil service and land management policies.

Historical Origins and Development

The Russian serfdom system originated in the 16th century, evolving from feudal obligations tied to land ownership and solidifying under Tsarist autocracy, binding peasants to estates with limited rights. In contrast, China's Han system, developed during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), was characterized by centralized bureaucratic governance and a land distribution model that included state land and tenancy arrangements, emphasizing Confucian social order. Both systems shaped agrarian economies and social hierarchies, with Russian serfdom persisting until the 19th century, while the Han land system laid foundations for later imperial administrative practices.

Legal Status of Peasants and Serfs

The Russian serfdom system legally bound peasants to the land, rendering them the property of landlords with limited personal freedoms and obligations to provide labor or produce. In contrast, the Han system categorized peasants as free subjects with state protection, granting them land-use rights while imposing tax and corvee labor duties, but without private ownership over their persons. This fundamental difference in legal status meant Russian serfs faced hereditary servitude and severe restrictions, whereas Han peasants maintained a conditional but recognized autonomy under imperial law.

Social Hierarchies and Class Structure

The Russian serfdom system featured a rigid social hierarchy with serfs legally bound to the land and under the control of nobles, creating a distinct divide between landowners and peasants. In contrast, the Han Dynasty's social structure was based on a Confucian hierarchy emphasizing scholar-officials (shi), peasants, artisans, and merchants, where social mobility was possible through education and civil service exams. Both systems reinforced elite dominance but differed in legal status and pathways for social advancement within social classes.

Economic Roles and Contributions

The Russian serfdom system tied peasants to landowners, creating a labor force primarily engaged in agriculture, which sustained the feudal economy but limited technological and commercial development. In contrast, the Han system emphasized a bureaucratic structure and the well-organized peasantry, contributing to state stability through efficient tax collection and surplus production that supported public projects and military campaigns. Both systems shaped their economies differently, with Russian serfdom reinforcing agrarian dependency and the Han system promoting centralized economic management and infrastructure growth.

Land Ownership and Agricultural Practices

The Russian serfdom system centralized land ownership under the nobility, with serfs bound to estates, limiting their autonomy and agricultural innovation. In contrast, the Han system featured state-controlled lands alongside privately owned plots, promoting decentralized agricultural practices and allowing peasants more direct involvement in land use. While Russian serfs primarily engaged in subsistence farming under coercive labor obligations, Han agriculture benefited from advancements such as iron tools and crop rotation to enhance productivity.

Government Control and Administration

The Russian serfdom system centralized control through noble landowners who administered serfs under the tsarist autocracy, ensuring agricultural productivity while maintaining rigid social hierarchies. In contrast, the Han system implemented a bureaucratic governance model with Confucian scholars managing local administration through an imperial civil service examining both land and labor. Government control in Russia was decentralized to the nobility, whereas the Han dynasty employed a meritocratic bureaucracy to enforce imperial policies directly across provinces.

Daily Life and Labor Conditions

Russian serfdom imposed harsh labor conditions where peasants were tied to the land, obligated to provide unpaid labor to landowners, often working long hours in agriculture with minimal personal freedom. In contrast, the Han system in ancient China emphasized corvee labor and state service, with peasants required to contribute labor for infrastructure projects and military conscription, but maintained some community autonomy and periodic relief from duties. Daily life for Russian serfs was marked by extreme dependence on landlords and scarce resources, whereas Han peasants experienced a more organized, state-controlled labor structure that balanced agricultural duties with state-imposed obligations.

Systems of Punishment and Mobility

The Russian serfdom system enforced strict corporal and economic punishments including physical beatings, forced labor, and restrictions on movement, severely limiting serfs' social mobility. In contrast, the Han system, while utilizing legalist punishments such as fines, forced labor, and exile, allowed for greater social mobility through examination and bureaucratic recruitment, enabling individuals to ascend the social hierarchy. Both systems employed punishment to maintain social order, but the Han system provided institutional pathways for upward mobility absent in Russian serfdom.

Abolition and Long-term Impact

The Russian Serfdom system was abolished in 1861 through Tsar Alexander II's Emancipation Reform, freeing millions of serfs but leaving many bound by redemption payments and land shortages, which hindered economic development and social mobility for decades. In contrast, the Han system in ancient China, characterized by state-managed land and labor, gradually declined without a formal abolition, leading to reforms that redistributed land and eased peasants' burdens over time. The long-term impact of Russian emancipation fostered social upheaval and eventual revolutionary movements, while Han agricultural reforms contributed to the stability and continuity of Chinese imperial governance.

Russian Serfdom System Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com