Concurrent cause occurs when two or more factors simultaneously contribute to an event or outcome, each independently capable of causing the result. Understanding how concurrent causes interplay is crucial for accurate legal or insurance claim assessments, where liability and responsibility must be clearly established. Explore this article to learn how concurrent cause principles affect your case and decision-making process.

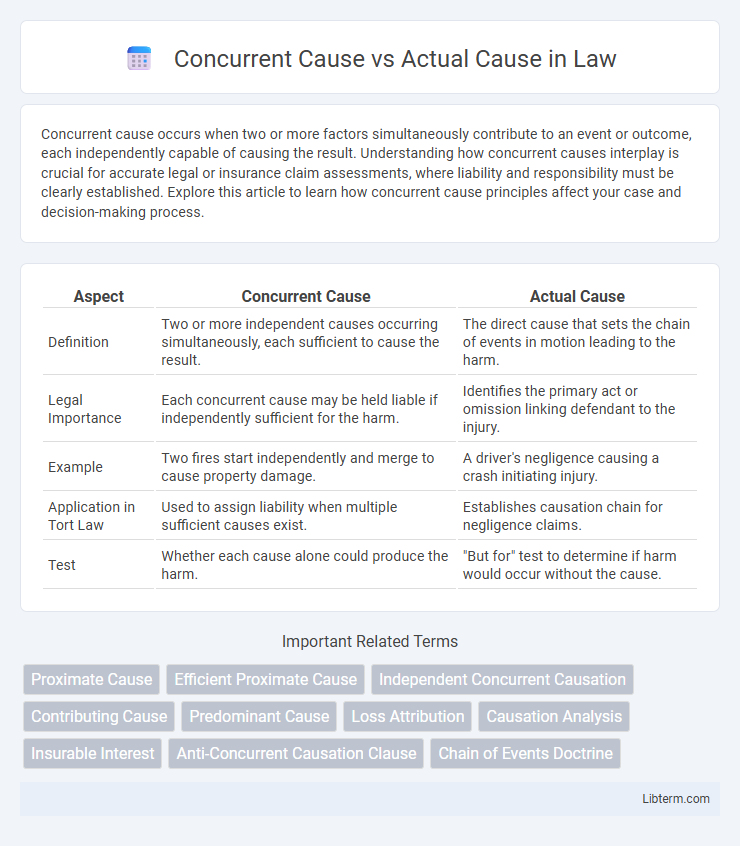

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Concurrent Cause | Actual Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Two or more independent causes occurring simultaneously, each sufficient to cause the result. | The direct cause that sets the chain of events in motion leading to the harm. |

| Legal Importance | Each concurrent cause may be held liable if independently sufficient for the harm. | Identifies the primary act or omission linking defendant to the injury. |

| Example | Two fires start independently and merge to cause property damage. | A driver's negligence causing a crash initiating injury. |

| Application in Tort Law | Used to assign liability when multiple sufficient causes exist. | Establishes causation chain for negligence claims. |

| Test | Whether each cause alone could produce the harm. | "But for" test to determine if harm would occur without the cause. |

Understanding Concurrent Cause vs Actual Cause

Concurrent cause refers to multiple independent events occurring simultaneously, each contributing to the same result, while actual cause identifies the specific event that directly produces the outcome. Understanding the distinction hinges on recognizing that actual cause is the primary factor without which the effect would not occur, whereas concurrent causes operate together, making it difficult to isolate a single source. In legal and scientific analysis, accurately identifying actual cause amid concurrent causes is crucial for assigning responsibility and understanding causality.

Definition of Actual Cause in Law

Actual cause in law, also known as "cause-in-fact," refers to an enduring factual connection between a defendant's conduct and the resulting harm, established through the "but-for" test, meaning the harm would not have occurred but for the defendant's actions. Concurrent cause arises when two or more independent causes combine to bring about harm, each sufficient on its own to cause the injury. The distinction is critical in tort law as actual cause determines liability by linking the defendant's conduct directly to the plaintiff's injury.

What is Concurrent Cause?

Concurrent cause refers to a situation in legal or insurance contexts where two or more independent events or sources contribute simultaneously to a loss or damage. Each cause operates concurrently, meaning they collectively result in the harm, making it challenging to isolate a single actual cause. Understanding concurrent causes is essential for determining liability or claim payouts when multiple factors lead to the same adverse outcome.

Key Legal Doctrines Involving Causation

Concurrent cause refers to situations where two or more independent causes combine to result in harm, each sufficient on its own, whereas actual cause (or cause-in-fact) identifies the specific action that directly led to the injury through the "but-for" test. Key legal doctrines involving causation include the substantial factor test, which applies when multiple causes contribute to the harm, and the foreseeability doctrine, which limits liability to outcomes that a reasonable person could predict. Courts often distinguish between concurrent causes and intervening causes to determine liability, emphasizing whether the defendant's act was a substantial factor in producing the injury.

Differences Between Concurrent and Actual Causes

Concurrent causes involve multiple independent factors occurring simultaneously, each contributing to the final outcome, whereas actual cause refers to the specific factor that directly produces the effect. In legal and medical contexts, actual cause is identified through cause-in-fact tests such as the "but-for" test, while concurrent causes complicate liability since no single factor alone may have produced the harm. Understanding these differences is crucial for determining responsibility, as actual cause establishes direct causation, whereas concurrent cause addresses shared or combined causation.

Examples of Concurrent Cause in Real Cases

Concurrent cause occurs when two or more independent events simultaneously contribute to a loss, complicating liability determination. For example, in cases like concurrent fire and flood damage to property, both natural disasters collectively caused the total destruction. Another example includes simultaneous engine failure and pilot error leading to an aircraft accident, where both factors independently exacerbated the outcome.

Proving Actual Cause in Court

Proving actual cause in court requires establishing a direct link between the defendant's conduct and the plaintiff's injury, demonstrating that the harm would not have occurred "but for" the defendant's actions. Concurrent cause involves multiple independent factors contributing to the injury, complicating causation analysis as the court must determine whether each cause was sufficient to produce the harm. Legal standards for actual cause emphasize concrete evidence, such as expert testimony and factual records, to meet the burden of proof for causation beyond a reasonable doubt.

Legal Implications of Concurrent Causes

Concurrent causes arise when two or more independent events simultaneously contribute to a harmful outcome, complicating the determination of legal liability. Courts often apply the substantial factor test to establish actual cause, requiring that each cause be a significant contributor to the harm for liability to attach. Legal implications of concurrent causes include potential joint liability among parties and complex apportionment of damages based on each cause's impact.

How Courts Handle Multiple Causes

Courts analyze concurrent causes by determining whether each cause independently contributed to the harm, often applying the substantial factor test to establish liability. When multiple actual causes are involved, courts may hold each defendant responsible if their actions were significant enough to cause the injury, even if not the sole cause. This approach ensures fair apportionment of damages and avoids injustice when separate acts combine to produce a single harm.

Best Practices for Lawyers Addressing Causation

Lawyers should distinguish between concurrent cause--where multiple independent factors contribute simultaneously to harm--and actual cause, which establishes the direct cause-effect relationship in liability. Best practices include thoroughly gathering and analyzing evidence to identify each cause's role and applying clear legal standards to determine the weight of concurrent causes versus singular actual causes. Expert testimony and precise legal arguments enhance the ability to prove causation in complex cases involving multiple contributing factors.

Concurrent Cause Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com