A contingent situation depends on specific conditions or events that may or may not happen, making outcomes uncertain. Understanding the nuances of contingent agreements helps you prepare for possible scenarios and mitigate risks effectively. Explore the article further to discover key insights on managing contingent factors in various contexts.

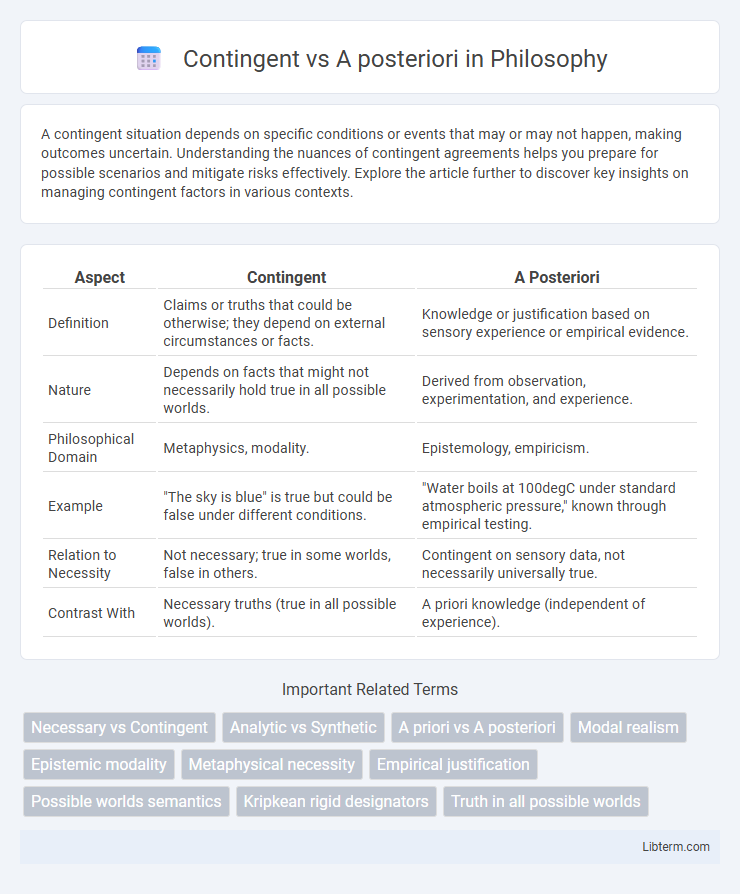

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Contingent | A Posteriori |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Claims or truths that could be otherwise; they depend on external circumstances or facts. | Knowledge or justification based on sensory experience or empirical evidence. |

| Nature | Depends on facts that might not necessarily hold true in all possible worlds. | Derived from observation, experimentation, and experience. |

| Philosophical Domain | Metaphysics, modality. | Epistemology, empiricism. |

| Example | "The sky is blue" is true but could be false under different conditions. | "Water boils at 100degC under standard atmospheric pressure," known through empirical testing. |

| Relation to Necessity | Not necessary; true in some worlds, false in others. | Contingent on sensory data, not necessarily universally true. |

| Contrast With | Necessary truths (true in all possible worlds). | A priori knowledge (independent of experience). |

Understanding Contingent and A Posteriori: Key Definitions

Contingent propositions are statements whose truth depends on empirical facts and could be otherwise, meaning they are true in some possible worlds and false in others. A posteriori knowledge is information gained through sensory experience or observation, contrasting with a priori knowledge which is independent of experience. Understanding that contingent truths require empirical verification helps distinguish them from necessary truths, which are true by definition and known a priori.

Historical Background of the Terms

The terms "contingent" and "a posteriori" originate from classical philosophy and epistemology, with "contingent" tracing back to Aristotle's exploration of possibility and necessity in metaphysics. "A posteriori" knowledge, rooted in Scholastic philosophy, was elaborated by thinkers like Thomas Aquinas to describe knowledge derived from empirical experience, contrasting with "a priori" knowledge. The development of these concepts was pivotal in shaping debates on the sources and certainty of knowledge throughout the history of Western philosophy.

Philosophical Roots: Contingency and Empiricism

Contingency in philosophy, rooted in Aristotle's Metaphysics, refers to truths or facts that could have been otherwise, emphasizing the variability of existence and conditions. A posteriori knowledge, central to empiricism pioneered by John Locke and David Hume, depends on sensory experience and observation for justification, contrasting with a priori reasoning which is independent of experience. The philosophical roots of contingency and empiricism intersect in the inquiry into how knowledge relates to the variability and evidence of the empirical world.

Main Differences Between Contingent and A Posteriori

Contingent truths depend on the way the world actually is and can vary based on empirical evidence, whereas a posteriori knowledge is specifically derived from sensory experience or observation. Contingency relates to the truth value of propositions being non-necessary and possibly false, while a posteriori status categorizes knowledge acquisition methods rather than necessity. The main difference lies in contingency addressing the nature of propositions' truth, and a posteriori focusing on the epistemological process of knowledge validation through experience.

Contingent Truths: Nature and Examples

Contingent truths depend on the way the world happens to be and are true in some possible worlds but not in others, such as "The Eiffel Tower is in Paris." These truths can only be known a posteriori since their truth value relies on empirical observation or experience rather than pure reason. Examples include statements like "Water boils at 100degC at sea level" and "Barack Obama was the 44th President of the United States," which require sensory evidence or historical knowledge for validation.

A Posteriori Knowledge: Nature and Examples

A posteriori knowledge is derived from empirical evidence and sensory experience, making it contingent on observation rather than pure reasoning. Scientific discoveries, such as the boiling point of water or the chemical composition of substances, exemplify a posteriori knowledge since they require experimentation and verification. This type of knowledge contrasts with a priori knowledge, which is independent of experience and based solely on logic or innate understanding.

Overlapping Areas: Where Contingent Meets A Posteriori

Contingent truths are facts that depend on the way the world actually is, while a posteriori knowledge is derived from empirical observation. The overlapping area occurs when contingent truths are known through empirical experience, illustrating that some contingent facts require a posteriori verification. Examples include scientific discoveries, where empirical data confirms the contingency of natural phenomena.

Key Thinkers and Philosophical Debates

David Hume is a key thinker in the debate between contingent and a posteriori knowledge, emphasizing empirical evidence as the foundation of a posteriori truths that depend on experience. Immanuel Kant challenged Hume by introducing the concept of synthetic a priori knowledge, which is necessary yet informative, bridging the gap between contingent empirical knowledge and necessary a priori propositions. Contemporary philosophers continue to debate the implications of this distinction for metaphysics, epistemology, and the limits of human understanding, focusing on how necessity, possibility, and experience interact in the formation of knowledge.

Real-World Implications and Applications

Contingent truths depend on empirical evidence and can change based on real-world observations, impacting scientific theories and everyday decision-making. A posteriori knowledge, derived from experience, underpins fields such as physics, medicine, and social sciences where data-driven validation is critical. Understanding the distinction guides how policies, technologies, and ethical judgments are formed in response to evolving evidence.

Conclusion: The Importance in Philosophical Inquiry

Understanding the distinction between contingent and a posteriori statements is crucial for philosophical inquiry as it clarifies how knowledge is obtained and justified. Contingent truths depend on empirical evidence and can change based on new observations, whereas a posteriori knowledge is derived from experience and sensory data. Recognizing this difference helps philosophers evaluate arguments, assess the validity of claims, and refine epistemological theories.

Contingent Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com