The social contract is a foundational theory in political philosophy that explains the legitimacy of state authority based on an implicit agreement among individuals to form a society. It outlines mutual obligations where citizens consent to certain rules and governance structures in exchange for protection and social order. Discover how understanding the social contract can deepen your insight into modern political systems and your role within them by reading the full article.

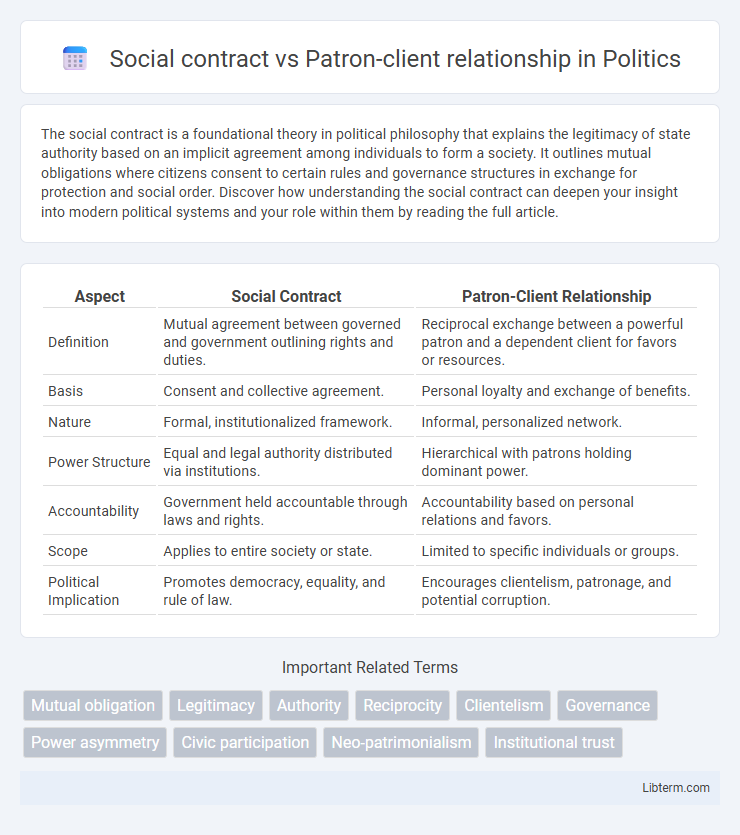

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Social Contract | Patron-Client Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Mutual agreement between governed and government outlining rights and duties. | Reciprocal exchange between a powerful patron and a dependent client for favors or resources. |

| Basis | Consent and collective agreement. | Personal loyalty and exchange of benefits. |

| Nature | Formal, institutionalized framework. | Informal, personalized network. |

| Power Structure | Equal and legal authority distributed via institutions. | Hierarchical with patrons holding dominant power. |

| Accountability | Government held accountable through laws and rights. | Accountability based on personal relations and favors. |

| Scope | Applies to entire society or state. | Limited to specific individuals or groups. |

| Political Implication | Promotes democracy, equality, and rule of law. | Encourages clientelism, patronage, and potential corruption. |

Understanding the Social Contract: Definition and Origins

The social contract is a foundational political theory concept that defines an implicit agreement among individuals to form a society and accept certain rules for mutual benefit, originating from philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. This contract establishes the legitimacy of state authority and the obligation of citizens to obey laws in exchange for protection and social order. Unlike patron-client relationships, which are based on personal ties and reciprocal favors, the social contract is an abstract, collective arrangement centered on equality and shared governance.

Key Features of the Patron-Client Relationship

The patron-client relationship is characterized by asymmetrical power dynamics where the patron offers resources, protection, or opportunities in exchange for loyalty and support from the client. This system relies on personal ties and mutual obligations rather than formal laws or institutional frameworks seen in social contracts. Unlike the social contract's emphasis on collective governance and rights, patron-client relationships operate through informal networks and reciprocal favors within hierarchical social structures.

Historical Evolution: Social Contract vs Patron-Client Systems

Social contract theory emerged during the Enlightenment, emphasizing mutual agreements between individuals and rulers to establish political legitimacy, as seen in the works of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. Patron-client systems have deeper historical roots in ancient and classical societies, where hierarchical, reciprocal bonds between powerful patrons and dependent clients structured social, economic, and political life. Over time, social contracts influenced the development of modern democratic states, while patron-client relationships persisted in various forms within traditional and informal political networks.

Core Principles: Authority, Obligation, and Reciprocity

The social contract centers on mutual consent where authority arises from collective agreement, obligations are codified and enforceable, and reciprocity is based on equal rights and duties among citizens. In contrast, the patron-client relationship features hierarchical authority vested in the patron, obligations are personal and often informal, and reciprocity involves asymmetric exchanges of protection for loyalty or services. These core principles reflect distinct frameworks of governance and social order, with the social contract emphasizing institutional legitimacy and the patron-client dynamic rooted in personal dependency and exchange.

Power Dynamics and Social Hierarchies

Social contracts establish power dynamics based on mutual consent and legal frameworks, promoting equality and shared obligations between citizens and governing bodies. Patron-client relationships hinge on asymmetrical power structures, where patrons hold authority and resources while clients depend on patrons for protection and favors, reinforcing entrenched social hierarchies. These contrasting systems reflect fundamental differences in legitimacy and reciprocity within societal power arrangements.

Role of Trust and Legitimacy in Both Models

Trust in a social contract is foundational, as citizens grant authority to a government perceived as legitimate, ensuring compliance through shared norms and institutional accountability. In contrast, patron-client relationships rely heavily on personalized trust between individuals, where legitimacy stems from reciprocal obligations and direct exchanges of support rather than formal legal frameworks. Both models depend on trust and legitimacy, but social contracts emphasize institutional legitimacy, while patron-client systems prioritize personal loyalty and mutual benefit.

Comparative Analysis: Governance and Accountability

The social contract establishes governance based on mutual consent and institutionalized accountability, where state authority is derived from the collective agreement of citizens to uphold laws and rights. In contrast, the patron-client relationship relies on personalized, hierarchical exchanges of favors and loyalty, often resulting in informal mechanisms of governance with limited transparency and accountability. Comparative analysis highlights that social contracts promote structured rule of law and democratic accountability, whereas patron-client systems tend to perpetuate patronage networks and blurred responsibilities within governance frameworks.

Impact on Social Cohesion and Political Stability

The social contract fosters social cohesion and political stability by promoting mutual obligations and collective agreement between citizens and the state, ensuring rule of law and equal rights. In contrast, patron-client relationships undermine social cohesion by creating dependency networks based on favoritism and personal loyalty, which can lead to political fragmentation and weakened institutional trust. Consequently, the social contract supports inclusive governance and long-term stability, while patron-client dynamics often perpetuate inequality and political volatility.

Modern Examples and Applications in Society

Social contracts form the foundation of modern democratic governance, exemplified by constitutional frameworks in countries such as the United States and Germany, where citizens grant authority to government institutions in exchange for protection of rights and public services. In contrast, patron-client relationships remain prevalent in sectors like business networking and political patronage systems in regions such as Southeast Asia and parts of Latin America, where reciprocal obligations between powerful patrons and dependent clients influence resource distribution and social mobility. The differentiation highlights how structured legal agreements contrast with personalized, informal exchanges shaping power dynamics and societal organization in contemporary contexts.

Challenges and Critiques of Each Relationship Model

The social contract model faces challenges related to the assumption of rational consent and equal power among participants, often critiqued for overlooking inequalities and coercion in society. Patron-client relationships are criticized for fostering dependency, perpetuating power imbalances, and undermining democratic institutions by prioritizing personal loyalty over public accountability. Both models struggle with issues of legitimacy and representation, complicating their effectiveness in diverse and complex political environments.

Social contract Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com