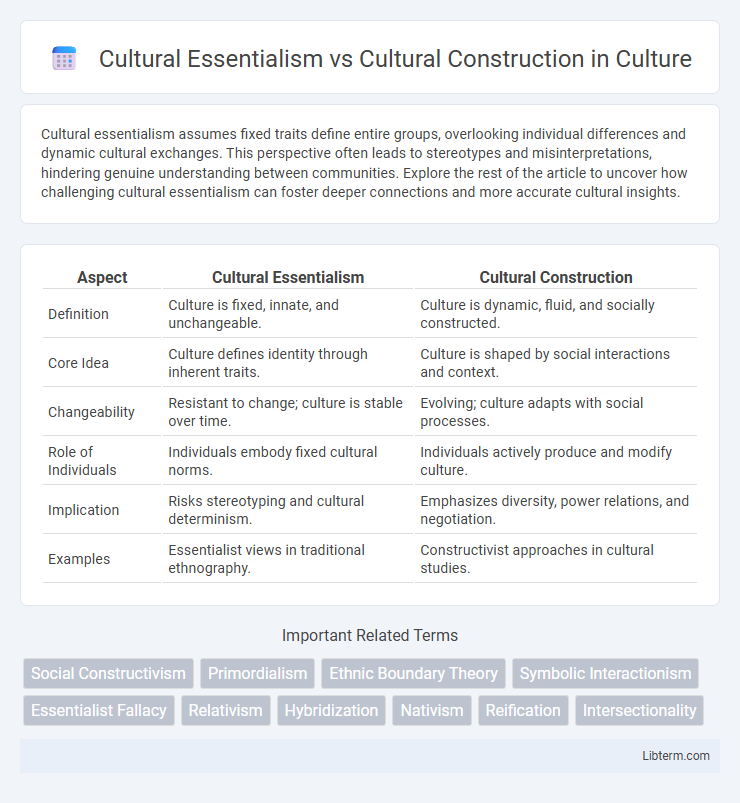

Cultural essentialism assumes fixed traits define entire groups, overlooking individual differences and dynamic cultural exchanges. This perspective often leads to stereotypes and misinterpretations, hindering genuine understanding between communities. Explore the rest of the article to uncover how challenging cultural essentialism can foster deeper connections and more accurate cultural insights.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Cultural Essentialism | Cultural Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Culture is fixed, innate, and unchangeable. | Culture is dynamic, fluid, and socially constructed. |

| Core Idea | Culture defines identity through inherent traits. | Culture is shaped by social interactions and context. |

| Changeability | Resistant to change; culture is stable over time. | Evolving; culture adapts with social processes. |

| Role of Individuals | Individuals embody fixed cultural norms. | Individuals actively produce and modify culture. |

| Implication | Risks stereotyping and cultural determinism. | Emphasizes diversity, power relations, and negotiation. |

| Examples | Essentialist views in traditional ethnography. | Constructivist approaches in cultural studies. |

Understanding Cultural Essentialism: Core Concepts

Cultural essentialism asserts that distinct cultures possess inherent, unchanging traits that define their identity and behaviors, often simplifying complex social dynamics into fixed characteristics. This perspective emphasizes the idea that culture is a stable essence passed down through generations, shaping individuals' beliefs and practices uniformly within a group. Understanding cultural essentialism involves recognizing how it can lead to stereotyping by ignoring cultural diversity, internal variation, and the evolving nature of cultural identities.

Defining Cultural Construction: An Overview

Cultural construction refers to the idea that cultural meanings and social realities are created through interactions, language, and shared practices rather than being innate or fixed. This perspective emphasizes how cultural norms, identities, and values are shaped by historical, social, and political contexts, challenging the notion of inherent cultural traits. Understanding cultural construction allows for analysis of how power dynamics and social institutions influence perceptions of culture and identity over time.

Historical Roots of Essentialist Thinking

Historical roots of cultural essentialism trace back to Enlightenment-era theories that categorized societies into fixed, homogeneous groups based on perceived inherent traits. Early anthropologists and colonial administrators reinforced essentialist thinking by emphasizing racial and cultural hierarchies, which justified imperial domination and social stratification. These foundational ideas laid the groundwork for debates opposing cultural constructionism, which views culture as dynamic, fluid, and shaped by historical and social contexts.

Key Theorists in Cultural Constructionism

Cultural constructionism, shaped significantly by theorists like Clifford Geertz and Michel Foucault, argues that cultural realities are socially constructed and fluid rather than fixed or essential. Geertz's interpretive anthropology emphasizes culture as a system of shared meanings shaped through symbols and rituals, while Foucault's discourse theory highlights power relations in the creation and deployment of cultural knowledge. These perspectives contrast with cultural essentialism by rejecting innate cultural traits and focusing on the dynamic processes of meaning-making within societies.

Essentialism vs Constructionism: Main Differences

Cultural Essentialism posits that cultures have fixed, inherent traits that define their identity, emphasizing unchanging characteristics passed through generations. Cultural Constructionism argues that culture is fluid and continuously shaped by social interactions, power dynamics, and historical contexts, rejecting the idea of static cultural essences. The main difference lies in essentialism's focus on innate, stable cultural attributes versus constructionism's view of culture as an evolving, socially constructed phenomenon.

The Impact of Essentialism on Social Identity

Cultural essentialism asserts fixed, inherent traits within social groups, shaping rigid social identities that often limit individual expression and reinforce stereotypes. This perspective impacts social identity by promoting exclusionary practices and perpetuating social divisions based on perceived innate cultural differences. In contrast, recognizing cultural identity as socially constructed allows for a more fluid and dynamic understanding, fostering inclusivity and reducing prejudice.

Cultural Construction and the Fluidity of Identity

Cultural construction emphasizes that identity is not fixed but fluid, shaped continuously by social interactions, historical contexts, and power dynamics. Rather than having inherent or essential traits, cultural identities evolve through discourse and lived experiences, allowing individuals to navigate multiple, overlapping affiliations. This fluidity challenges static definitions and highlights the complexity of how people relate to culture and community.

Critiques of Essentialist Approaches

Critiques of cultural essentialism emphasize its reductionist nature, which oversimplifies diverse cultural identities into fixed, homogeneous categories, ignoring internal differences and social dynamics. This perspective often perpetuates stereotypes and neglects the fluidity and hybridity of cultures shaped by historical, social, and political contexts. Scholars argue cultural constructionism better captures the evolving and negotiated nature of cultural meanings, challenging the static assumptions inherent in essentialist frameworks.

Real-World Applications of Constructionist Perspectives

Cultural constructionist perspectives emphasize that culture is shaped through social interactions, language, and shared symbols, influencing identity formation and collective behavior in real-world settings. This approach informs practices in multicultural education, where curricula adapt to diverse cultural narratives rather than fixed traits, enhancing cross-cultural understanding. In organizational contexts, it promotes inclusive leadership by recognizing cultural identities as fluid and negotiated rather than static, facilitating better teamwork and innovation.

Moving Forward: Bridging Essentialism and Constructionism

Bridging cultural essentialism and constructionism involves recognizing fixed cultural traits while embracing fluid social dynamics to foster inclusive identities. Integrating essentialist perspectives on heritage with constructionist views on cultural change enables nuanced dialogues that respect tradition alongside innovation. This balanced approach promotes mutual understanding in multicultural societies by validating enduring cultural markers and encouraging evolving cultural expressions.

Cultural Essentialism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com