Collective farms revolutionized agriculture by pooling resources and labor to increase productivity and efficiency in rural areas. Understanding the historical, economic, and social impacts of collective farming reveals its role in shaping modern agricultural practices. Explore the rest of the article to learn how collective farms continue to influence farming today and what it means for your agricultural knowledge.

Table of Comparison

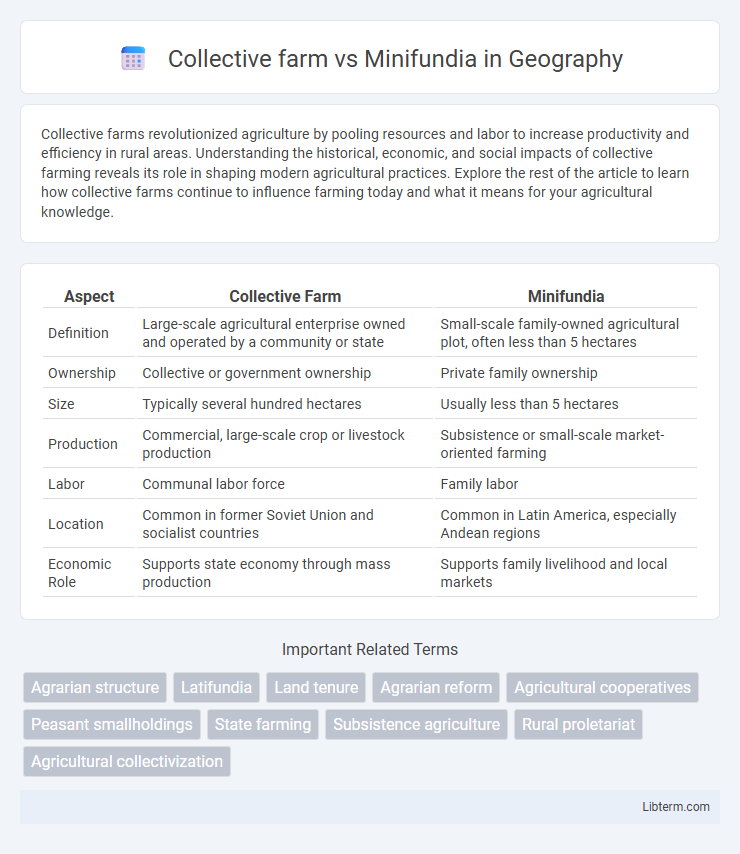

| Aspect | Collective Farm | Minifundia |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Large-scale agricultural enterprise owned and operated by a community or state | Small-scale family-owned agricultural plot, often less than 5 hectares |

| Ownership | Collective or government ownership | Private family ownership |

| Size | Typically several hundred hectares | Usually less than 5 hectares |

| Production | Commercial, large-scale crop or livestock production | Subsistence or small-scale market-oriented farming |

| Labor | Communal labor force | Family labor |

| Location | Common in former Soviet Union and socialist countries | Common in Latin America, especially Andean regions |

| Economic Role | Supports state economy through mass production | Supports family livelihood and local markets |

Introduction to Collective Farms and Minifundia

Collective farms, common in socialist economies, consolidate numerous small landholdings into a single large-scale agricultural operation managed collectively by workers, aiming to increase productivity and resource efficiency through shared labor and machinery. Minifundia are small-scale, family-owned plots typically found in Latin America, characterized by limited land size and subsistence farming practices that prioritize household food security over commercial production. The contrast between collective farms and minifundia highlights differing agricultural models shaped by land ownership, labor organization, and economic objectives.

Historical Background of Collective Farms

Collective farms, established primarily during the Soviet Union's agricultural reforms in the 1920s and 1930s, aimed to consolidate individual landholdings into large, state-controlled enterprises to increase agricultural productivity and support industrialization. This system contrasted sharply with minifundia, small-scale family farms prevalent in Latin America, characterized by fragmented land ownership and subsistence farming. The historical backdrop of collective farms reflects state-driven collectivization policies that often led to significant social and economic upheaval, whereas minifundia emerged from traditional land tenure patterns and local agricultural practices.

Origins and Evolution of Minifundia

Minifundia originated during the colonial period in Latin America as small, subsistence farms inherited by multiple generations, leading to fragmented plots and limited agricultural productivity. Unlike collective farms established under socialist regimes to pool resources and centralize production, minifundia evolved through historical land tenure systems emphasizing individual family ownership. The persistence of minifundia reflects socio-economic factors such as inheritance customs, land scarcity, and rural poverty, shaping agrarian structures distinct from state-controlled collective farms.

Key Characteristics of Collective Farms

Collective farms, also known as kolkhozes, are large-scale agricultural enterprises where land, labor, and resources are pooled together by members who share profits according to their contribution, contrasting with minifundia, which are small, family-operated farms with individual ownership. Collective farms emphasize mechanization, centralized management, and cooperative labor, enabling higher productivity through shared equipment and inputs. These farms often receive state support and operate under government regulations, aiming to increase agricultural output and efficiency on a broad scale.

Defining Features of Minifundia

Minifundia are small-scale agricultural plots typically less than five hectares, characterized by family-based labor and traditional farming techniques that prioritize subsistence over commercial production. These farms often rely on diverse cropping systems and manual tools, maintaining ecological balance through crop rotation and mixed planting. Unlike collective farms, which emphasize centralized management and large-scale production, minifundia foster local autonomy and preserve cultural agricultural practices.

Socioeconomic Impact: Collective Farms vs Minifundia

Collective farms, characterized by large-scale state-operated agricultural enterprises, often drive higher productivity and resource efficiency, enabling significant rural employment and infrastructural development, but may inhibit individual land ownership and local autonomy. Minifundia, small family-owned plots prevalent in Latin America, promote subsistence farming and preserve traditional livelihoods while frequently suffering from low productivity and poverty due to limited access to capital and technology. The socioeconomic impact of these systems reflects a trade-off between economic growth and social equity, with collective farms potentially fostering modernization at the cost of social dislocation, whereas minifundia sustain cultural identity but struggle with economic sustainability.

Land Ownership Models Compared

Collective farms involve communal land ownership where resources and outputs are shared among members, often implemented under state control to increase agricultural productivity. Minifundia are small, individually owned plots typically used by subsistence farmers, emphasizing personal land tenure and localized farming practices. The key difference lies in collective ownership and cooperative labor on collective farms versus private ownership and family-based management on minifundia.

Productivity and Efficiency Analysis

Collective farms, characterized by large-scale cooperative management, often achieve higher productivity through economies of scale, mechanization, and centralized resource allocation. Minifundia, small family-owned plots, tend to exhibit greater efficiency in labor input due to intensive, diversified cultivation tailored to local conditions but face limitations in capital investment and technology adoption. Comparative studies reveal that while collective farms excel in output volume, minifundia optimize resource use per unit area, highlighting a trade-off between scale-driven productivity and micro-level efficiency.

Environmental Implications of Both Systems

Collective farms often lead to large-scale monoculture, increasing soil degradation and reducing biodiversity, whereas minifundia promote diverse crops that enhance soil health and ecosystem stability. The centralized machinery and chemical inputs in collective farms contribute to higher greenhouse gas emissions, while traditional practices in minifundia maintain lower carbon footprints. Water usage efficiency is generally better in minifundia due to smaller plot sizes and localized irrigation methods, contrasting with the extensive water demand of collective farming systems.

Future Trends and Policy Considerations

Collective farms, characterized by large-scale mechanized agriculture, face challenges in efficiency and sustainability, prompting policymakers to encourage diversification and incorporation of advanced technologies to improve productivity and environmental impact. Minifundia, smallholder farms with limited access to capital, benefit from targeted support programs focusing on access to credit, extension services, and market integration to boost income and food security. Future trends emphasize digital agriculture, climate-smart practices, and inclusive policies that balance mechanization with small-scale farming resilience to address global food security and rural livelihoods.

Collective farm Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com