Samurai were elite Japanese warriors renowned for their strict code of honor, discipline, and skill in martial arts. Their legacy influences modern culture, embodying values such as loyalty, bravery, and self-discipline. Explore this article to uncover the fascinating history and enduring impact of the samurai.

Table of Comparison

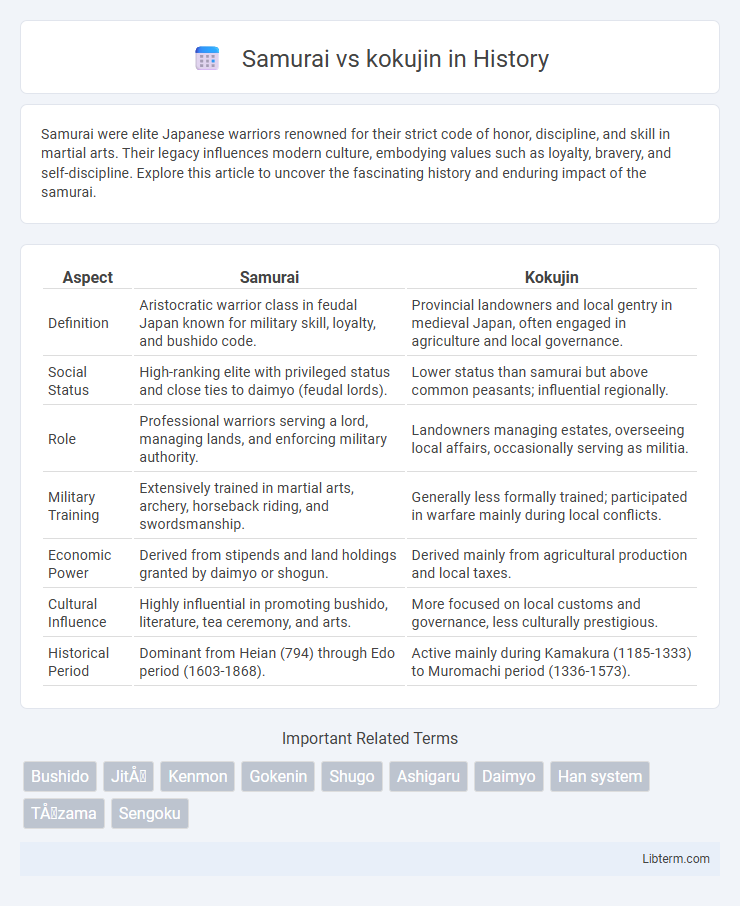

| Aspect | Samurai | Kokujin |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Aristocratic warrior class in feudal Japan known for military skill, loyalty, and bushido code. | Provincial landowners and local gentry in medieval Japan, often engaged in agriculture and local governance. |

| Social Status | High-ranking elite with privileged status and close ties to daimyo (feudal lords). | Lower status than samurai but above common peasants; influential regionally. |

| Role | Professional warriors serving a lord, managing lands, and enforcing military authority. | Landowners managing estates, overseeing local affairs, occasionally serving as militia. |

| Military Training | Extensively trained in martial arts, archery, horseback riding, and swordsmanship. | Generally less formally trained; participated in warfare mainly during local conflicts. |

| Economic Power | Derived from stipends and land holdings granted by daimyo or shogun. | Derived mainly from agricultural production and local taxes. |

| Cultural Influence | Highly influential in promoting bushido, literature, tea ceremony, and arts. | More focused on local customs and governance, less culturally prestigious. |

| Historical Period | Dominant from Heian (794) through Edo period (1603-1868). | Active mainly during Kamakura (1185-1333) to Muromachi period (1336-1573). |

Historical Origins of Samurai and Kokujin

Samurai originated in Japan during the Heian period as elite warriors serving the aristocracy, evolving into a powerful military class by the Kamakura era. Kokujin were provincial landowners and local elites who gained military and political influence during the Muromachi period, often competing with the samurai for regional control. The divergence between samurai as a professional warrior class and kokujin as territorial administrators shaped Japan's feudal structure.

Social Status and Class Distinctions

Samurai occupied a distinct elite class in feudal Japan, serving as the warrior nobility with exclusive privileges, including land ownership and political influence, while kokujin were powerful provincial landowners and local samurai without the same centralized authority. The social status of samurai was tied to their hereditary role and allegiance to daimyo or the shogunate, granting them higher prestige compared to kokujin, who often balanced agricultural leadership with minor military responsibilities. Class distinctions were marked by samurai's strict adherence to bushido and formal training, contrasting with the kokujin's more practical, regionally focused power that allowed some social mobility within the provincial hierarchy.

Roles in Feudal Japanese Society

Samurai served as the warrior elite, tasked with military duties, loyalty to their daimyo, and upholding Bushido codes, while kokujin were rural landowners who managed agricultural production and local governance. Samurai held higher social status and were often granted stipends or land for their service, whereas kokujin maintained regional influence through economic control and administrative roles. Their distinct but complementary functions sustained the hierarchical structure of feudal Japan, balancing martial prowess with agricultural stability.

Military Functions and Responsibilities

Samurai held elite military roles, responsible for strategic planning, battlefield leadership, and the enforcement of feudal law, often serving as mounted archers and skilled swordsmen. Kokujin, as provincial warriors or local samurai, managed regional defense duties, controlled landholdings, and upheld order within their territories. The hierarchical structure positioned samurai as high-ranking commanders, while kokujin fulfilled essential roles in territorial administration and troop mobilization.

Land Ownership and Economic Power

Samurai wielded significant economic power through their land ownership, granted by the shogunate as a source of income and military loyalty, which established a hierarchical feudal system in Japan. Kokujin, regional landowners and local samurai, held autonomous control over smaller territories, leveraging agricultural production to sustain their economic influence independently. The competition between samurai and kokujin centered on control of fertile land and resource management, shaping political stability and wealth distribution during the feudal era.

Samurai vs Kokujin: Code of Conduct and Ethics

Samurai adhered to Bushido, a strict code of conduct emphasizing loyalty, honor, and martial valor, guiding their actions in both warfare and daily life. Kokujin, Japanese provincial landowners, followed more flexible and pragmatic ethical standards centered on local governance and social obligations. The divergent codes reflected the Samurai's disciplined warrior ethos versus the Kokujin's focus on regional authority and resource management.

Political Influence and Alliances

Samurai, as elite military nobility, wielded significant political influence through their close ties to the shogunate and daimyo, shaping regional governance and policymaking. Kokujin, local landowners and lesser nobles, often formed strategic alliances with samurai to bolster their territorial control and political power within provinces. These alliances created a complex network of mutual support that influenced feudal hierarchies and power dynamics across medieval Japan.

Key Conflicts and Rivalries

Samurai and kokujin clashed primarily over land control and military authority during Japan's Sengoku period, with samurai upholding feudal loyalty to daimyo while kokujin sought autonomous power as local landholders. Conflicts intensified as kokujin resisted samurai-imposed taxation and conscription, challenging the traditional warrior hierarchy. Rivalries were marked by shifting alliances and battles for territorial dominance, underscoring the struggle between centralized samurai governance and regional kokujin independence.

Decline and Transformation in Modern Japan

The decline of the samurai class during the Meiji Restoration led to the transformation of kokujin, or local landowners, who gained increased political and economic power in modern Japan. As the samurai lost their feudal privileges and stipends, kokujin adapted by expanding their influence through landownership and involvement in emerging capitalist enterprises. This shift played a crucial role in Japan's modernization, blending traditional authority with new socio-economic structures.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

The samurai legacy profoundly shaped Japan's martial culture, emphasizing honor, discipline, and loyalty, which continue to influence modern Japanese values and arts such as kendo and bushido philosophy. In contrast, the kokujin, as regional landowners and warriors, played a significant role in local governance and agricultural development, contributing to the decentralization of power during the feudal era. The cultural impact of both classes is evident in literature, theater, and historical narratives that highlight their distinct societal roles and enduring influence on Japan's social and political structures.

Samurai Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com