The Tribute System in Imperial China structured diplomatic and trade relations by requiring neighboring states to acknowledge Chinese supremacy through regular tribute missions. This system reinforced China's political dominance and facilitated cultural exchange, fostering stability and mutual benefits across East Asia. Explore the full article to understand how this system shaped historical international relations and influenced your region's development.

Table of Comparison

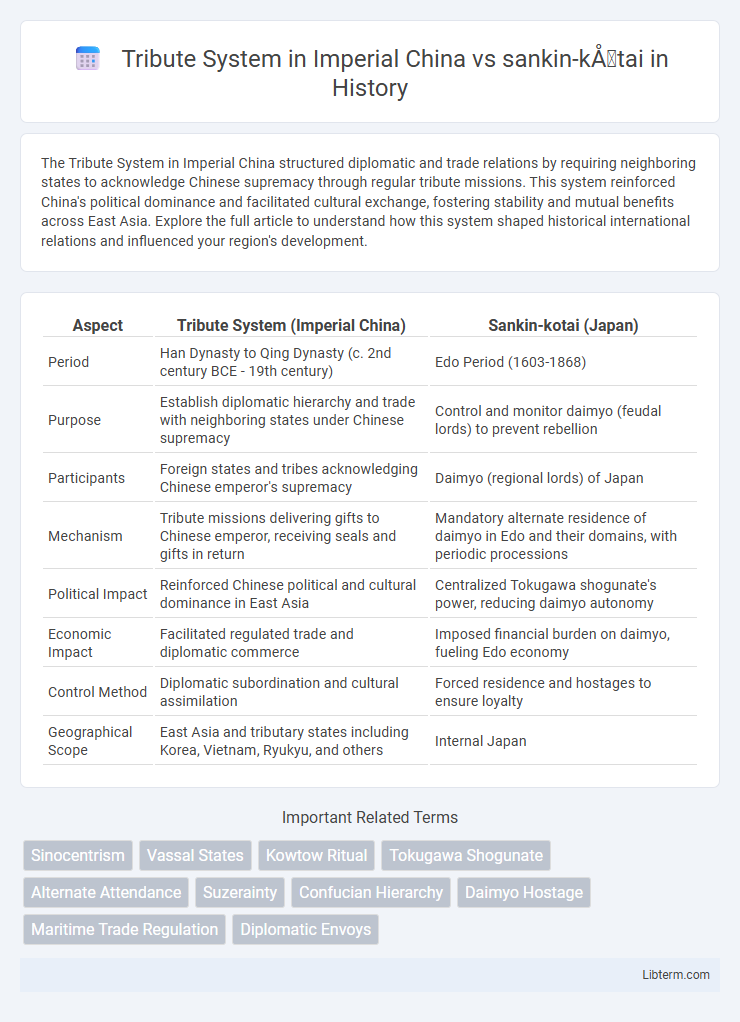

| Aspect | Tribute System (Imperial China) | Sankin-kotai (Japan) |

|---|---|---|

| Period | Han Dynasty to Qing Dynasty (c. 2nd century BCE - 19th century) | Edo Period (1603-1868) |

| Purpose | Establish diplomatic hierarchy and trade with neighboring states under Chinese supremacy | Control and monitor daimyo (feudal lords) to prevent rebellion |

| Participants | Foreign states and tribes acknowledging Chinese emperor's supremacy | Daimyo (regional lords) of Japan |

| Mechanism | Tribute missions delivering gifts to Chinese emperor, receiving seals and gifts in return | Mandatory alternate residence of daimyo in Edo and their domains, with periodic processions |

| Political Impact | Reinforced Chinese political and cultural dominance in East Asia | Centralized Tokugawa shogunate's power, reducing daimyo autonomy |

| Economic Impact | Facilitated regulated trade and diplomatic commerce | Imposed financial burden on daimyo, fueling Edo economy |

| Control Method | Diplomatic subordination and cultural assimilation | Forced residence and hostages to ensure loyalty |

| Geographical Scope | East Asia and tributary states including Korea, Vietnam, Ryukyu, and others | Internal Japan |

Introduction to Tribute System and Sankin-kōtai

The Tribute System in Imperial China functioned as a diplomatic framework where surrounding states acknowledged Chinese supremacy through regular tribute missions, fostering trade and political order under the Sinocentric world view. Sankin-kotai was a Japanese feudal policy during the Edo period requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and the shogun's capital, Edo, aimed at maintaining central control and preventing rebellion. Both systems established hierarchical relationships--China's through ritualized foreign diplomacy and Japan's via domestic political regulation--reflecting distinct methods of central authority reinforcement.

Historical Backgrounds of Imperial China and Tokugawa Japan

The Tribute System in Imperial China functioned as a hierarchical network of diplomatic and trade relations anchoring the Middle Kingdom's regional supremacy from the Han Dynasty through the Qing, characterized by subordinate states offering tributes for political legitimacy and trade privileges. In contrast, the Tokugawa Japan's sankin-kotai system, established in the early 17th century during the Edo period, enforced daimyo attendance in Edo to consolidate shogunal power and prevent rebellion, reflecting a domestic political mechanism rather than external diplomacy. Both systems exemplify state strategies to maintain order and control, with China projecting power through interstate ritualized hierarchy, while Tokugawa Japan employed internal mobilization and surveillance to stabilize feudal domains.

Core Principles of the Tribute System

The Tribute System in Imperial China was based on hierarchical diplomacy where foreign states acknowledged Chinese supremacy through ritual gift exchanges and tribute missions, reinforcing China's central role in East Asian political order. It emphasized moral superiority, Confucian values, and reciprocal obligations to maintain harmony and stability within the Sinocentric world. Unlike the Sankin-kotai system, which was a domestic control mechanism requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, the Tribute System shaped international relations through symbolic submission and ceremonial exchange.

Structure and Purpose of Sankin-kōtai

The Sankin-kotai system in Edo-period Japan required daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and the shogun's capital, ensuring political allegiance and central control through mandatory attendance and costly travel. This structured procession balanced power by limiting regional autonomy and facilitating surveillance, contrasting with Imperial China's Tribute System, which emphasized diplomatic hierarchy and economic exchange with neighboring states as a means of asserting imperial supremacy. Sankin-kotai functioned primarily as a domestic mechanism for internal stabilization, whereas the Tribute System operated as an external framework for international relations and legitimization of the emperor's authority.

Political Objectives: Control and Influence

The Tribute System in Imperial China exercised political control by reinforcing hierarchical relationships where neighboring states recognized Chinese supremacy, thereby extending Beijing's influence through diplomacy and ritualized exchanges. Sankin-kotai in Japan functioned as a mechanism of centralized control by requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, ensuring loyalty and minimizing potential rebellion against the Tokugawa shogunate. Both systems used structured obligations to maintain political stability and exert influence over subordinate regions, reflecting distinct but effective methods of governance in East Asian history.

Economic Impacts and Resource Flow

The Tribute System in Imperial China structured economic relations by regulating tributary states' resource flows, facilitating controlled exchange of luxury goods, silver, and silk that reinforced China's hegemonic status and boosted internal markets through increased demand for foreign products. Sankin-kotai in Edo Japan mandated daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and the Shogun's capital, driving extensive resource mobilization, regional economic integration, infrastructure development, and a consumer-driven market fueled by daimyo expenditure and retainers' activities. Both systems created significant economic impacts by channeling resources to central authority while stimulating regional economies, yet the Tribute System emphasized diplomatic-economic dominance via international trade, and sankin-kotai focused on domestic economic consolidation and social control.

Cultural Exchange and Symbolism

The Tribute System in Imperial China functioned as a diplomatic framework emphasizing hierarchical relations and symbolic submission, facilitating cultural exchange through ritualized gift-giving and recognition of the Chinese emperor's supremacy. Sankin-kotai in Edo-period Japan symbolized loyalty to the shogunate and promoted cultural diffusion by requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and the capital, fostering artistic and political integration. Both systems reinforced centralized authority while enabling controlled cultural interactions that shaped regional identities and political legitimacy.

Diplomatic Relations and Foreign Policy

The Tribute System in Imperial China structured diplomatic relations through hierarchical rituals where neighboring states acknowledged Chinese supremacy, facilitating controlled trade and political stability in East Asia. In contrast, Japan's sankin-kotai was an internal policy designed to maintain centralized authority over regional daimyos rather than direct foreign relations, emphasizing domestic control over external diplomacy. While the Tribute System solidified China's role as a regional hegemon through symbolic exchanges and tribute missions, sankin-kotai ensured internal cohesion without significantly impacting Japan's foreign policy or diplomatic posture.

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences

The Tribute System in Imperial China functioned as a diplomatic framework where neighboring states acknowledged Chinese supremacy through ritualistic gift exchanges and political submission, reinforcing Sino-centric hierarchy and cultural influence. In contrast, Japan's sankin-kotai was a feudal policy requiring daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, serving as a mechanism for the Tokugawa shogunate to maintain internal control and prevent rebellion. While the Tribute System emphasized external diplomatic relations and hierarchical order in East Asia, sankin-kotai focused on domestic political stability and centralized governance within Japan.

Legacy and Lasting Impacts on East Asia

The Tribute System in Imperial China established a hierarchical framework that reinforced Chinese cultural and political dominance across East Asia, promoting diplomatic relations and trade while shaping regional identities through Confucian values. Sankin-kotai, the Tokugawa shogunate's alternate attendance policy, centralized feudal power within Japan, stabilizing domestic governance and indirectly influencing East Asian political models by demonstrating controlled regional autonomy under a strong central authority. Both systems left enduring legacies by structuring inter-state relations and internal governance, deeply embedding concepts of hierarchy, loyalty, and political order in East Asian history.

Tribute System in Imperial China Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com