Barratry refers to the illegal act of consistently inciting lawsuits or disputes, often for personal gain or profit, which can disrupt legal and commercial practices. Understanding barratry is crucial for businesses and individuals to protect themselves from fraudulent legal tactics and avoid costly consequences. Explore this article to learn how barratry might impact your legal rights and how you can safeguard against it.

Table of Comparison

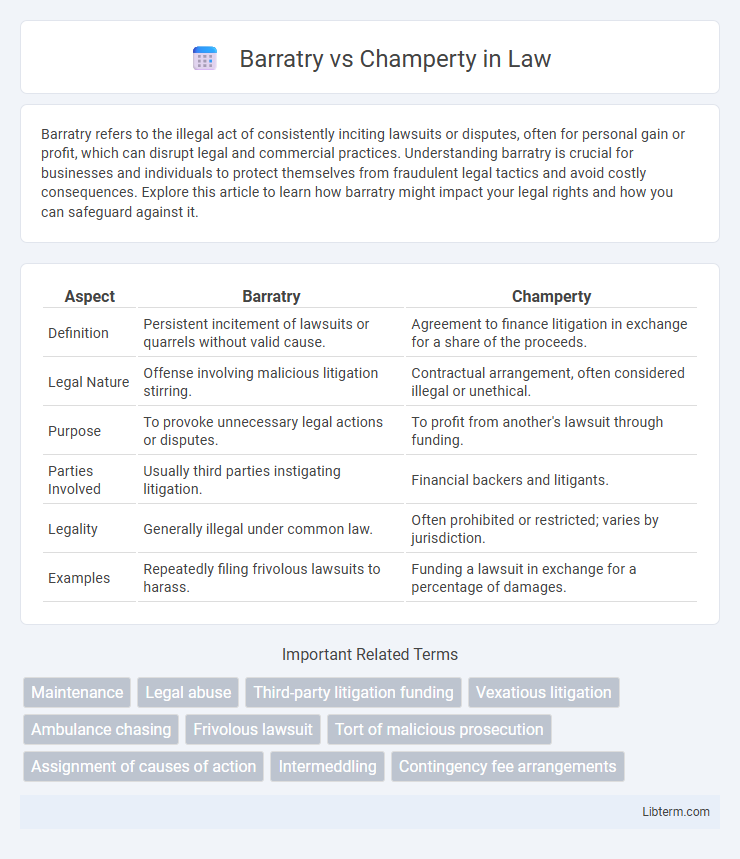

| Aspect | Barratry | Champerty |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Persistent incitement of lawsuits or quarrels without valid cause. | Agreement to finance litigation in exchange for a share of the proceeds. |

| Legal Nature | Offense involving malicious litigation stirring. | Contractual arrangement, often considered illegal or unethical. |

| Purpose | To provoke unnecessary legal actions or disputes. | To profit from another's lawsuit through funding. |

| Parties Involved | Usually third parties instigating litigation. | Financial backers and litigants. |

| Legality | Generally illegal under common law. | Often prohibited or restricted; varies by jurisdiction. |

| Examples | Repeatedly filing frivolous lawsuits to harass. | Funding a lawsuit in exchange for a percentage of damages. |

Understanding Barratry: Definition and Legal Context

Barratry refers to the persistent incitement of groundless legal actions, often by an attorney or litigant, to harass or profit illegally. In legal contexts, barratry undermines judicial resources and is recognized as a punishable offense to maintain court integrity. Distinct from champerty, which involves funding lawsuits for a share in the proceeds, barratry focuses on the initiation of frivolous or vexatious litigation.

What Is Champerty? Key Concepts and Meaning

Champerty refers to an agreement where a third party finances a lawsuit in exchange for a portion of the judgment or settlement, differing from barratry which involves the frequent incitement of groundless litigation. This legal concept aims to prevent exploitation of the judicial system by prohibiting third parties from acquiring an ownership interest in the proceeds of a lawsuit they have funded. Champerty is closely regulated because it can encourage frivolous lawsuits and undermine the integrity of the legal process.

Historical Origins of Barratry and Champerty

Barratry originated in medieval English common law, describing the offense of persistently inciting lawsuits or quarrels to generate profit, often tied to the disruption of public order. Champerty, emerging alongside barratry, involved an agreement where a third party supports litigation in exchange for a share of the judgment or settlement, initially viewed as unethical profiteering from another's legal dispute. Both doctrines developed to curb frivolous and exploitative lawsuits during a period when the legal system was vulnerable to manipulation by opportunistic litigants.

Core Differences Between Barratry and Champerty

Barratry involves the persistent incitement of groundless legal actions to harass or profit from litigation, while champerty specifically refers to an agreement where a third party finances another's lawsuit in exchange for a share of the proceeds. The core difference lies in barratry's emphasis on repetitive vexatious litigation without merit, whereas champerty centers on the financial backing of a lawsuit by a stranger to the dispute. Laws in jurisdictions like England and the United States distinguish these offenses to prevent abuse of the legal system and unauthorized profiteering from litigation.

Legal Elements Required for Barratry Cases

Barratry involves the repeated incitement of litigation without valid grounds, requiring proof of intentional instigation and misconduct by the accused. Essential legal elements include demonstrating habitual vexatious behavior, lack of genuine legal basis, and an intent to harass or profit from unnecessary lawsuits. The claimant must establish that the defendant's actions are aimed at disrupting justice or causing harm through frivolous legal processes, distinguishing barratry from champerty, which specifically entails an agreement to finance litigation for a share of the proceeds.

Essential Criteria for Champerty Agreements

Champerty requires a champertous agreement where a party with no prior interest in a lawsuit agrees to finance it in exchange for a share of the proceeds, distinguishing it from barratry, which involves persistent incitement of legal actions. Essential criteria for champerty agreements include a financial contribution to litigation, an agreement to share in the lawsuit's proceeds, and the defendant's lack of prior involvement or interest in the claim. Courts often scrutinize champerty to prevent abuses of the legal process through speculative litigation financing.

Modern Legal Perspectives on Barratry

Modern legal perspectives on barratry define it as the persistent incitement of groundless lawsuits, viewed as a public nuisance undermining judicial efficiency. Courts increasingly differentiate barratry from champerty, where champerty involves an agreement to finance a lawsuit for a share of the proceeds, emphasizing the ethical and procedural violations unique to barratry. Statutes and case law now treat barratry as a sanctionable offense to deter abusive litigation practices and uphold the integrity of the legal system.

Current Status and Regulation of Champerty

Champerty, once widely prohibited as a form of maintenance, has undergone significant legal reforms and is now subject to specific regulations in various jurisdictions, balancing the prevention of frivolous litigation with access to justice. Current status in common law countries demonstrates a shift towards controlled allowance of champertous agreements, particularly in litigation funding and contingency fee arrangements, with statutes delineating permissible terms and requiring disclosure and consent. Regulatory frameworks often include licensing requirements for third-party funders and obligations to avoid conflicts of interest, thereby ensuring ethical compliance while fostering fair legal recourse.

Notable Legal Cases Involving Barratry and Champerty

Notable legal cases involving barratry include *Henderson v. Henderson* (1843), which established principles against vexatious litigation, and *R v. McKay* (1911), highlighting the criminal nature of barratry in inciting lawsuits. In champerty, *Gilbert v. University of Aberdeen* (2001) clarified the distinctions between champertous agreements and legitimate third-party litigation funding. These cases underpin the legal framework distinguishing unlawful solicitation and funding of litigation from permissible legal conduct.

Barratry vs Champerty: Implications for the Legal Profession

Barratry involves the persistent incitement of lawsuits without just cause, often undermining the integrity of the legal system, while champerty refers to an agreement where a third party supports litigation in exchange for a share of the proceeds, raising ethical concerns about conflicts of interest. The distinction between barratry and champerty is crucial for legal professionals to maintain ethical standards and prevent frivolous or exploitative litigation practices. Understanding these doctrines helps lawyers navigate professional responsibilities, avoid malpractice risks, and uphold public trust in legal proceedings.

Barratry Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com