The Merger Doctrine plays a crucial role in contract law by determining that once a final written agreement is executed, prior oral or written negotiations merge into the contract, preventing any outside evidence from altering its terms. This principle ensures clarity and certainty in your contractual relationships by making the written contract the definitive record of the parties' agreement. Explore the rest of the article to understand how the Merger Doctrine impacts contract enforcement and dispute resolution.

Table of Comparison

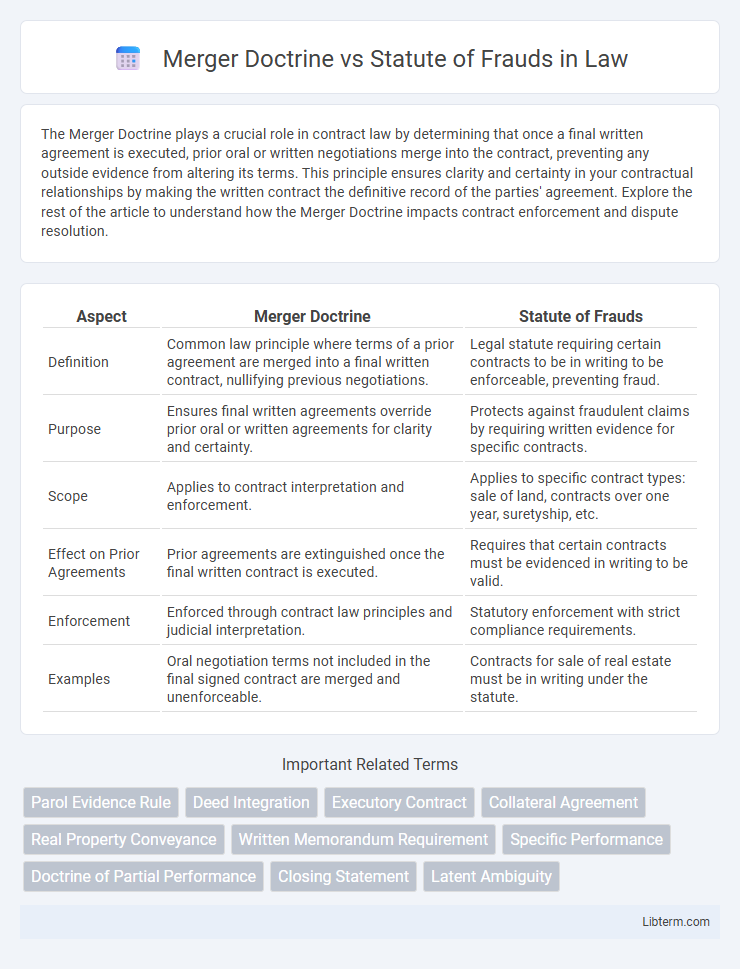

| Aspect | Merger Doctrine | Statute of Frauds |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Common law principle where terms of a prior agreement are merged into a final written contract, nullifying previous negotiations. | Legal statute requiring certain contracts to be in writing to be enforceable, preventing fraud. |

| Purpose | Ensures final written agreements override prior oral or written agreements for clarity and certainty. | Protects against fraudulent claims by requiring written evidence for specific contracts. |

| Scope | Applies to contract interpretation and enforcement. | Applies to specific contract types: sale of land, contracts over one year, suretyship, etc. |

| Effect on Prior Agreements | Prior agreements are extinguished once the final written contract is executed. | Requires that certain contracts must be evidenced in writing to be valid. |

| Enforcement | Enforced through contract law principles and judicial interpretation. | Statutory enforcement with strict compliance requirements. |

| Examples | Oral negotiation terms not included in the final signed contract are merged and unenforceable. | Contracts for sale of real estate must be in writing under the statute. |

Introduction to the Merger Doctrine and Statute of Frauds

The Merger Doctrine establishes that once a written contract is finalized, all prior negotiations or agreements related to the same subject matter are merged and superseded by the final written document. The Statute of Frauds requires certain types of contracts, such as those involving the sale of real estate or agreements that cannot be performed within one year, to be in writing to be legally enforceable. Understanding the interaction between the Merger Doctrine and the Statute of Frauds is essential for determining the validity and enforceability of contractual agreements.

Historical Background and Legal Foundations

The Merger Doctrine originated in common law to prevent parties from reneging on agreements once integrated into a formal contract, emphasizing the finality of written agreements over prior negotiations. The Statute of Frauds, first enacted in 1677 in England, requires certain contracts to be in writing to be legally enforceable, aiming to reduce fraud and misunderstandings in significant transactions. Both doctrines shape contract law by balancing evidentiary reliability with the enforcement of genuine agreements, rooted in centuries-old legal principles.

Definition and Scope: Merger Doctrine

The Merger Doctrine in contract law dictates that once a written agreement is signed, any prior oral or written agreements related to the same subject matter are considered merged into the final document, rendering earlier negotiations or promises unenforceable. This doctrine narrows the scope of enforceable terms strictly to those explicitly stated in the written contract, emphasizing the finality and exclusivity of the written instrument. It serves to prevent parties from contradicting or supplementing the integrated contract with external evidence, thereby promoting certainty and reducing disputes over prior agreements.

Definition and Scope: Statute of Frauds

The Statute of Frauds is a legal doctrine requiring certain contracts to be in writing and signed to be enforceable, primarily covering agreements such as those involving real estate, contracts lasting over one year, and sale of goods exceeding a specific value. Its scope ensures clarity and prevents fraudulent claims by mandating documented evidence of the parties' intentions. Unlike the Merger Doctrine, which addresses the integration of prior negotiations into a final written contract, the Statute of Frauds specifically governs the enforceability threshold based on written formalities.

Key Differences Between the Doctrines

The Merger Doctrine states that once a contract is integrated into a final written agreement, prior oral or written negotiations cannot alter its terms, emphasizing completeness and finality in contract enforcement. The Statute of Frauds requires certain contracts, such as those involving real estate or agreements lasting over one year, to be in writing to be legally enforceable, focusing on preventing fraud through insufficient evidence. Key differences include the Merger Doctrine's role in preventing modification of integrated contracts versus the Statute of Frauds' function in mandating written evidence to establish the existence of specific contracts.

Application in Real Estate Transactions

The Merger Doctrine in real estate transactions dictates that once a property deed is delivered and accepted, the terms of the prior contract merge into the deed, limiting enforcement to the deed's contents. In contrast, the Statute of Frauds requires certain real estate agreements to be in writing to be enforceable, preventing oral contracts from having legal effect. Together, these doctrines ensure clarity and finality in property transfers by emphasizing written documentation and extinguishing earlier contract claims after deed delivery.

Exceptions and Limitations

The Merger Doctrine limits prior agreements by integrating all terms into a final written contract, thereby excluding earlier oral or written statements unless exceptions apply. Key exceptions include collateral contracts, subsequent modifications, and evidence of fraud, duress, or mistake, which allow extrinsic evidence despite the merger. The Statute of Frauds requires certain contracts to be in writing to be enforceable but allows exceptions such as partial performance, promissory estoppel, and admissions that validate oral agreements beyond the statute's limitations.

Impact on Contractual Rights and Remedies

The Merger Doctrine eliminates prior oral or written agreements once a final written contract is executed, limiting parties' rights and remedies strictly to those outlined in the integrated document. The Statute of Frauds requires certain contracts to be in writing to be enforceable, protecting parties from fraudulent claims and ensuring clarity of agreed terms for contractual rights. Together, these doctrines restrict the ability to introduce extrinsic evidence, shaping enforcement and remedies by emphasizing formal documentation in contract disputes.

Case Law Illustrations

Case law illustrates the interaction between the Merger Doctrine and the Statute of Frauds through decisions like *Stewart v. Senter*, where courts held that prior oral agreements are merged into a final written contract, rendering earlier promises unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds. In *Miller v. Latham*, the court emphasized that the Merger Doctrine prevents evidence of prior agreements when a written contract exists, reinforcing the Statute of Frauds requirement for certain contracts to be in writing to be enforceable. These cases highlight how the Merger Doctrine serves as a judicial tool to uphold the Statute of Frauds by ensuring only written contracts govern the parties' rights and obligations.

Practical Tips for Legal Practitioners

Legal practitioners should meticulously review contracts to ensure that all essential terms are explicitly stated, as the Merger Doctrine can nullify prior oral or written agreements not included in the final contract. Understanding how the Statute of Frauds requires certain contracts to be in writing helps prevent unenforceability issues, particularly in real estate, marriage agreements, and contracts exceeding one year. Practitioners must draft clear integration clauses and maintain thorough documentation to navigate conflicts between these doctrines effectively and protect clients from potential disputes.

Merger Doctrine Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com