Constructivism emphasizes that learning is an active, constructive process where individuals build new knowledge based on their experiences. This approach encourages critical thinking and problem-solving, empowering learners to connect concepts meaningfully. Explore the rest of the article to understand how constructivism can transform your educational strategies.

Table of Comparison

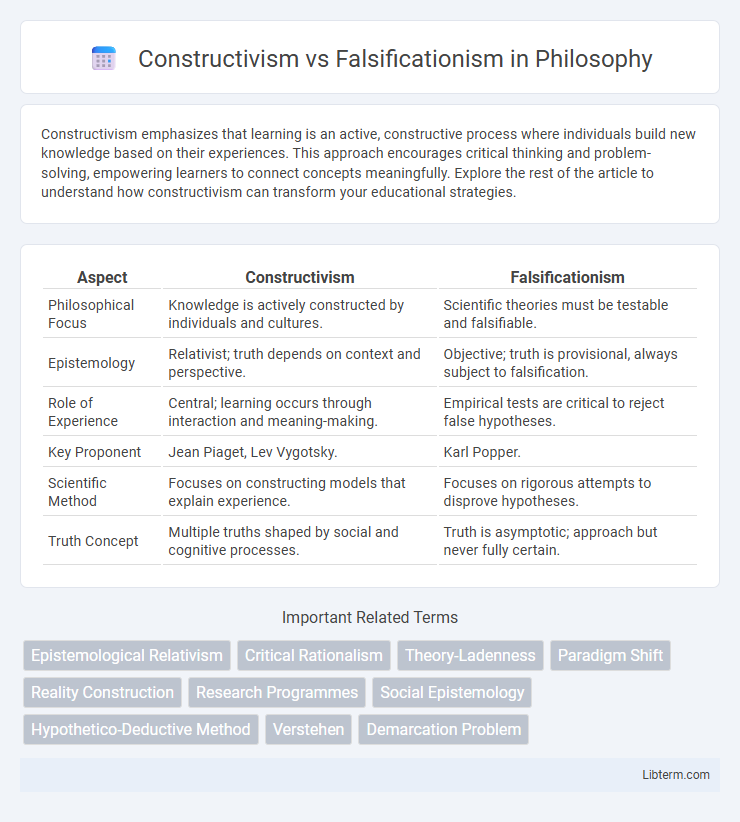

| Aspect | Constructivism | Falsificationism |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Focus | Knowledge is actively constructed by individuals and cultures. | Scientific theories must be testable and falsifiable. |

| Epistemology | Relativist; truth depends on context and perspective. | Objective; truth is provisional, always subject to falsification. |

| Role of Experience | Central; learning occurs through interaction and meaning-making. | Empirical tests are critical to reject false hypotheses. |

| Key Proponent | Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky. | Karl Popper. |

| Scientific Method | Focuses on constructing models that explain experience. | Focuses on rigorous attempts to disprove hypotheses. |

| Truth Concept | Multiple truths shaped by social and cognitive processes. | Truth is asymptotic; approach but never fully certain. |

Introduction to Constructivism and Falsificationism

Constructivism asserts that knowledge is actively constructed by individuals through experience and interaction with their environment, emphasizing the subjective nature of understanding. Falsificationism, introduced by Karl Popper, posits that scientific theories cannot be conclusively proven but can only be rigorously tested and potentially falsified to advance knowledge. Both approaches challenge traditional notions of epistemology by highlighting different mechanisms--constructive learning processes versus empirical refutation--in the development of scientific knowledge.

Historical Background of Both Philosophies

Constructivism emerged primarily from the works of Jean Piaget in the early 20th century, emphasizing knowledge as actively constructed by learners through experience and interaction. Falsificationism, developed by Karl Popper in the 1930s, arose as a critical response to classical inductivism, proposing that scientific theories cannot be conclusively proven but only falsified through empirical testing. Both philosophies significantly shaped the philosophy of science, with Constructivism influencing educational theory and Falsificationism advancing the criteria for scientific demarcation.

Key Principles of Constructivism

Constructivism emphasizes that knowledge is actively constructed by learners through experience and interaction rather than passively received, highlighting concepts like cognitive development and scaffolding. It asserts that understanding is subjective and context-dependent, shaped by social, cultural, and historical factors, which contrasts with the objective testing focus of Falsificationism. Key principles include the importance of learner-centered instruction, the role of prior knowledge in new learning, and the continuous adaptation of understanding through reflection and dialogue.

Core Tenets of Falsificationism

Falsificationism centers on the principle that scientific theories must be inherently disprovable through empirical testing, emphasizing the importance of refutability over verification. Karl Popper, the main proponent, argued that scientific knowledge advances by rigorously attempting to falsify hypotheses rather than confirming them, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of confirmation bias. This approach contrasts with constructivism's view that knowledge is socially constructed, highlighting falsificationism's commitment to objective, empirical criteria for scientific validation.

Epistemological Differences

Constructivism posits that knowledge is actively constructed by individuals through cognitive processes, emphasizing the subjective and context-dependent nature of understanding. Falsificationism, grounded in the philosophy of science, asserts that scientific knowledge advances through the systematic refutation of hypotheses, prioritizing empirical testability and objective criteria. The epistemological distinction lies in constructivism's focus on knowledge as a mental construct shaped by experience, while falsificationism views knowledge as provisional claims subject to falsification through empirical evidence.

Impact on Scientific Methodology

Constructivism emphasizes the co-creation of scientific knowledge through social processes and interpretive frameworks, highlighting the role of context and human perception in shaping scientific theories. Falsificationism, championed by Karl Popper, prioritizes rigorous testing and the refutation of hypotheses as the cornerstone of scientific progress, fostering a methodology centered on empirical scrutiny and potential falsifiability. The contrasting impacts on scientific methodology reveal constructivism's focus on knowledge as mutable and socially constructed, while falsificationism drives objective, test-driven inquiry aimed at eliminating false claims to approach truth.

Criticisms and Limitations

Constructivism faces criticism for its potential relativism, often questioned for lacking objective criteria to validate knowledge claims and risking subjectivity in scientific inquiry. Falsificationism is limited by its reliance on empirical refutability, which critics argue excludes theories that are not easily testable or that require a long time to falsify, such as certain hypotheses in theoretical physics. Both paradigms struggle with the complexity of scientific progress, where knowledge development is influenced by social, historical, and cognitive factors beyond strict construction or falsification.

Influence on Contemporary Science

Constructivism shapes contemporary science by emphasizing the socially constructed nature of scientific knowledge, highlighting the role of cultural, historical, and contextual factors in shaping scientific theories. Falsificationism, pioneered by Karl Popper, influences modern scientific methods through its focus on testability and the continuous process of refutation, promoting rigorous hypothesis testing and empirical scrutiny. Together, these philosophies drive the dynamic evolution of science by balancing interpretive frameworks with empirical rigor.

Case Studies: Constructivism vs Falsificationism in Practice

Case studies reveal that constructivism emphasizes the co-creation of knowledge through social interactions and context-specific understanding, often observed in educational and organizational settings where meaning evolves dynamically. Falsificationism, grounded in Karl Popper's philosophy, prioritizes rigorous hypothesis testing and empirical refutation to advance scientific knowledge, as demonstrated in experimental sciences where theories are systematically challenged. Practical applications show constructivism fosters adaptive learning environments, while falsificationism ensures robustness and cumulative progress in scientific inquiry.

Conclusion: Bridging the Philosophical Divide

Constructivism emphasizes knowledge as a human-constructed process shaped by social and cognitive factors, while falsificationism prioritizes empirical testing and refutation as the core of scientific progress. Bridging this philosophical divide requires acknowledging the constructive nature of theory formation alongside rigorous empirical validation. Integrating both perspectives fosters a more comprehensive understanding of scientific knowledge development, balancing creative synthesis with critical scrutiny.

Constructivism Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com