A basin is a natural or artificial depression on Earth's surface that collects and channels water, playing a crucial role in hydrology and environmental management. Understanding basin dynamics helps in predicting flood patterns, managing water resources, and preserving ecosystems. Explore the rest of the article to learn how basins impact your local environment and water systems.

Table of Comparison

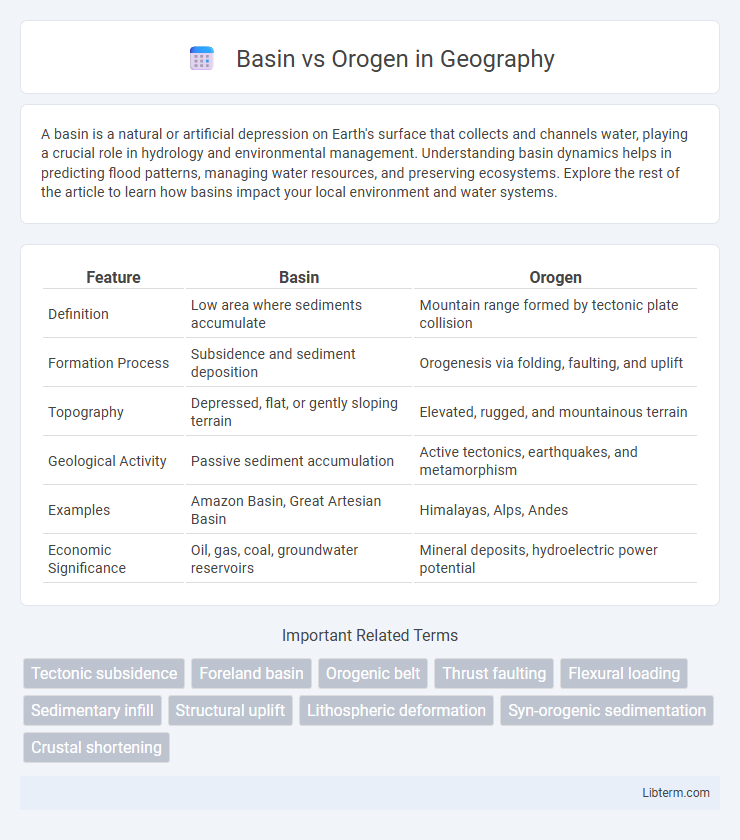

| Feature | Basin | Orogen |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Low area where sediments accumulate | Mountain range formed by tectonic plate collision |

| Formation Process | Subsidence and sediment deposition | Orogenesis via folding, faulting, and uplift |

| Topography | Depressed, flat, or gently sloping terrain | Elevated, rugged, and mountainous terrain |

| Geological Activity | Passive sediment accumulation | Active tectonics, earthquakes, and metamorphism |

| Examples | Amazon Basin, Great Artesian Basin | Himalayas, Alps, Andes |

| Economic Significance | Oil, gas, coal, groundwater reservoirs | Mineral deposits, hydroelectric power potential |

Introduction to Basins and Orogens

Basins are low-lying geological depressions where sediments accumulate over time, often formed by subsidence related to tectonic activities. Orogens, in contrast, are mountain-building regions created by the collision and deformation of tectonic plates, characterized by intense metamorphism and structural complexity. Understanding the distinct processes governing basins and orogens is crucial for interpreting Earth's tectonic evolution and sedimentary record.

Geological Definitions: Basin vs Orogen

A basin is a low-lying geological depression where sediments accumulate over time, often formed by subsidence due to tectonic activity or crustal extension. An orogen represents a region of mountain-building resulting from the collision and convergence of tectonic plates, characterized by intense deformation, metamorphism, and crustal thickening. Basins typically host sedimentary sequences, while orogens exhibit structural complexities such as folds, faults, and metamorphic grade variations.

Formation Processes of Basins

Sedimentary basins form primarily through tectonic subsidence caused by processes such as crustal stretching, lithospheric cooling, and sediment loading, creating accommodation space for sediment accumulation. These basins often develop in rift zones, foreland regions adjacent to orogens, or back-arc settings where extensional forces predominate. The interplay of mantle dynamics, crustal deformation, and sediment deposition governs basin evolution, distinctly differing from orogens, which result mainly from crustal shortening and mountain building through convergent tectonics.

Formation Mechanisms of Orogens

Orogen formation mechanisms primarily involve tectonic plate interactions such as continental collision, subduction, and terrane accretion, which result in crustal thickening and mountain building. These processes generate intense deformation, metamorphism, and magmatism within convergent plate boundaries, distinguishing orogens from sediment-filled basins formed mainly through subsidence. Key examples include the Himalayas formed by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates, showcasing the dynamic nature of orogeny driven by convergent tectonics.

Tectonic Settings: Basins Versus Orogens

Basins typically form in extensional tectonic settings where the Earth's crust is thinning, leading to sediment accumulation and subsidence, while orogens develop in compressional tectonic settings characterized by crustal shortening and mountain building. Basins often correspond to divergent plate boundaries or intracontinental rift zones, whereas orogens are associated with convergent plate boundaries and collisional tectonics. The contrasting tectonic regimes result in distinct structural features, rock deformation patterns, and sedimentary processes in basins versus orogenic belts.

Structural Differences: Basin vs Orogen

Basins are primarily characterized by subsidence and sediment accumulation within relatively stable or flexed crustal regions, exhibiting predominantly extensional or neutral structural regimes with gentle to moderate deformation. Orogens display intense compressional forces, resulting in mountain building, crustal thickening, and complex folding and faulting patterns, often including thrust faults and nappes. Structural contrasts reflect basins' accommodation of sediments through flexure or thermal subsidence, while orogens manifest tectonic convergence and crustal shortening.

Sedimentation in Basins and Orogenic Activity

Sedimentation in basins primarily accumulates thick sequences of clastic and chemical deposits derived from weathering and erosion of surrounding highlands, often preserving valuable records of past environmental and tectonic conditions. Orogenic activity, characterized by mountain building through tectonic plate collisions and crustal deformation, influences sedimentation patterns by creating topographic relief that controls erosion rates and sediment supply to adjacent basins. The interplay between basin subsidence and orogenic uplift governs sediment thickness, grain size distribution, and facies variations, crucial for hydrocarbon exploration and understanding crustal dynamics.

Economic Significance: Resources in Basins and Orogens

Basins are rich in hydrocarbon deposits such as oil and natural gas, making them crucial for the energy industry and economic development. Orogens, formed by mountain-building processes, often contain valuable mineral deposits including metals like gold, copper, and iron, essential for mining and industrial applications. The economic significance of basins lies in fossil fuel extraction, while orogens contribute primarily through metal ore mining and associated industries.

Global Examples of Basins and Orogens

The Amazon Basin exemplifies extensive sedimentary basins characterized by thick accumulations of sediments resulting from prolonged subsidence and deposition, whereas the Himalayas represent a prime example of an orogen formed by continental collision and mountain building processes. The Western Interior Basin in North America and the Parana Basin in South America further illustrate sedimentary basins with significant hydrocarbon potential. The Alpine orogeny in Europe and the Andean mountain belt in South America showcase complex orogenic belts resulting from tectonic plate interactions and crustal deformation.

Comparative Analysis: Basin vs Orogen

Basins are low-lying depressions where sediments accumulate, typically characterized by subsidence and sediment infill, whereas orogens are mountain belts formed by tectonic plate convergence and crustal deformation. Basin formation involves extension or crustal thinning, leading to sediment accommodation, while orogeny results from compressional forces causing folding, faulting, and uplift. The sedimentary records in basins contrast with the metamorphic and structural complexities observed in orogens, highlighting distinct geological processes and tectonic settings.

Basin Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com