Hospital-acquired infections pose a significant risk to patients by prolonging hospital stays and increasing healthcare costs. Understanding the causes, prevention methods, and treatment options is essential for improving patient outcomes and ensuring a safer healthcare environment. Explore the rest of this article to learn how your healthcare facility can minimize the risks associated with these infections.

Table of Comparison

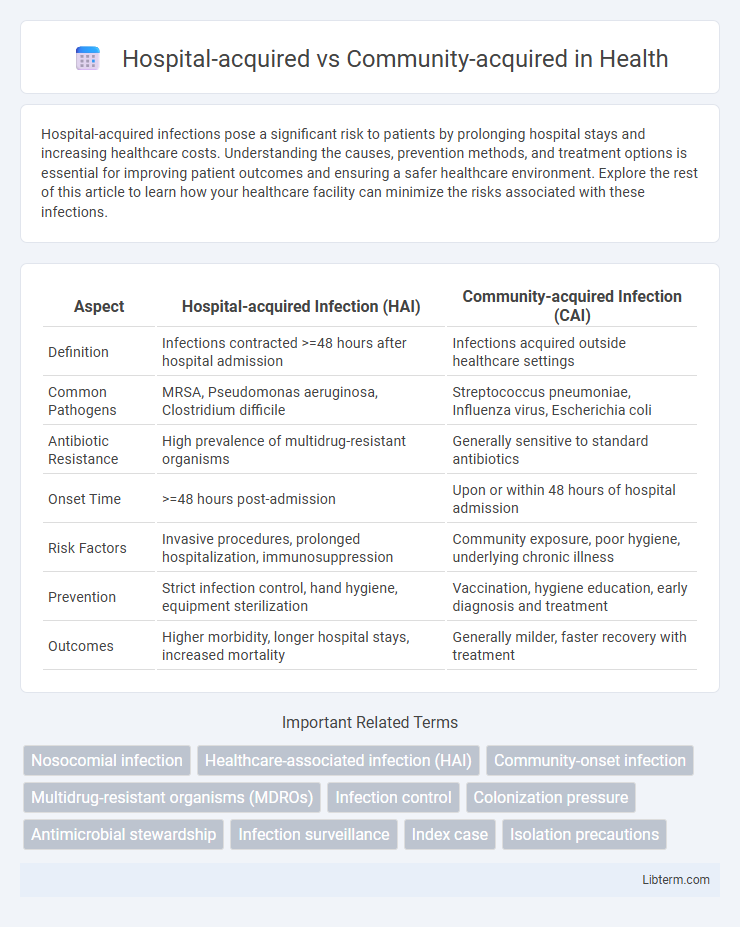

| Aspect | Hospital-acquired Infection (HAI) | Community-acquired Infection (CAI) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Infections contracted >=48 hours after hospital admission | Infections acquired outside healthcare settings |

| Common Pathogens | MRSA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium difficile | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Influenza virus, Escherichia coli |

| Antibiotic Resistance | High prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms | Generally sensitive to standard antibiotics |

| Onset Time | >=48 hours post-admission | Upon or within 48 hours of hospital admission |

| Risk Factors | Invasive procedures, prolonged hospitalization, immunosuppression | Community exposure, poor hygiene, underlying chronic illness |

| Prevention | Strict infection control, hand hygiene, equipment sterilization | Vaccination, hygiene education, early diagnosis and treatment |

| Outcomes | Higher morbidity, longer hospital stays, increased mortality | Generally milder, faster recovery with treatment |

Introduction to Hospital-acquired and Community-acquired Infections

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), also known as nosocomial infections, occur 48 hours or more after hospital admission and were not present or incubating at the time of admission. Community-acquired infections (CAIs) develop outside healthcare settings or within 48 hours of hospitalization, indicating exposure in the general community. The distinction between HAIs and CAIs is critical for infection control, antibiotic stewardship, and epidemiological surveillance in healthcare systems.

Key Definitions and Distinctions

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), also known as nosocomial infections, develop 48 hours or more after hospital admission and were absent at the time of admission, while community-acquired infections are present or incubating prior to hospital entry. Key distinctions include the pathogens involved: HAIs often involve antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, whereas community-acquired infections are typically caused by more antibiotic-sensitive strains. Understanding these differences is crucial for infection control strategies and selecting empirical antibiotic therapy.

Common Pathogens in Hospital-acquired Infections

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) frequently involve pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Clostridioides difficile. These microorganisms demonstrate increased resistance to multiple antibiotics, complicating treatment protocols in healthcare settings. In contrast, community-acquired infections often involve less resistant strains, emphasizing the importance of targeted infection control measures within hospitals.

Prevalent Pathogens in Community-acquired Infections

Community-acquired infections (CAIs) commonly involve pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which are frequent causes of respiratory tract infections. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus are also prevalent, especially in urinary tract infections and skin infections, respectively. Recognition of these pathogens is crucial for effective empirical treatment and antibiotic stewardship in outpatient settings.

Risk Factors for Hospital-acquired Infections

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) primarily arise due to extended hospital stays, invasive procedures such as catheterization or surgery, and the presence of multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings. Patients with weakened immune systems, those in intensive care units, and individuals receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics face higher susceptibility to HAIs. Environmental factors like contaminated medical equipment, inadequate hand hygiene, and overcrowded facilities further elevate the risk of hospital-acquired infections.

Risk Factors for Community-acquired Infections

Community-acquired infections commonly arise from exposure to pathogens in everyday environments such as schools, workplaces, and public spaces, with risk factors including close contact with infected individuals and poor hygiene practices. Underlying chronic conditions, such as diabetes or respiratory diseases, increase susceptibility by weakening the immune response. Limited access to preventive healthcare measures like vaccinations and timely antibiotic treatment also elevates the risk of acquiring infections outside hospital settings.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Approaches

Hospital-acquired infections often present with atypical clinical manifestations due to patients' compromised immunity and exposure to multidrug-resistant organisms, whereas community-acquired infections typically show more classic symptoms in otherwise healthy individuals. Diagnostic approaches for hospital-acquired infections require advanced microbiological techniques, such as molecular assays and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, to identify resistant pathogens, while community-acquired infections are commonly diagnosed through standard cultures and rapid antigen tests. Imaging modalities like chest X-rays or CT scans assist in detecting infections in both settings, but hospital-acquired infections necessitate more frequent use of invasive sampling to guide precise treatment.

Treatment Strategies and Antibiotic Resistance

Hospital-acquired infections frequently require more aggressive treatment strategies due to higher incidences of multidrug-resistant organisms such as MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, demanding use of broad-spectrum antibiotics or combination therapy. Community-acquired infections often respond to narrower-spectrum antibiotics based on typical susceptibility patterns, but empirical treatment must consider local resistance trends to prevent therapeutic failure. Monitoring antibiotic resistance profiles and adjusting treatment protocols accordingly is critical in both settings to optimize patient outcomes and reduce the spread of resistant pathogens.

Prevention and Control Measures

Hospital-acquired infections require stringent infection control measures including hand hygiene protocols, sterilization of medical equipment, and isolation of infected patients to prevent transmission within healthcare settings. Community-acquired infections necessitate public health strategies such as vaccination programs, education on personal hygiene, and early detection to reduce spread in the general population. Effective prevention combines environmental cleaning, antimicrobial stewardship, and timely identification of cases to minimize infection rates in both hospital and community contexts.

Comparative Outcomes and Prognosis

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) generally present with higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to community-acquired infections (CAIs), due to multidrug-resistant pathogens and compromised patient conditions. Outcomes for HAIs often involve prolonged hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and greater risk of complications, while CAIs typically have better prognostic profiles with more effective empiric treatment options. Prognosis in CAIs is more favorable, driven by early detection and intervention, whereas adverse outcomes in HAIs stem from delayed diagnosis and therapeutic challenges linked to resistant organisms.

Hospital-acquired Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com