Regurgitation occurs when undigested food is brought back up from the stomach into the mouth without the forceful contractions of vomiting. It can result from various medical conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or esophageal disorders. Discover the causes, symptoms, and treatments to manage your health effectively by reading the full article.

Table of Comparison

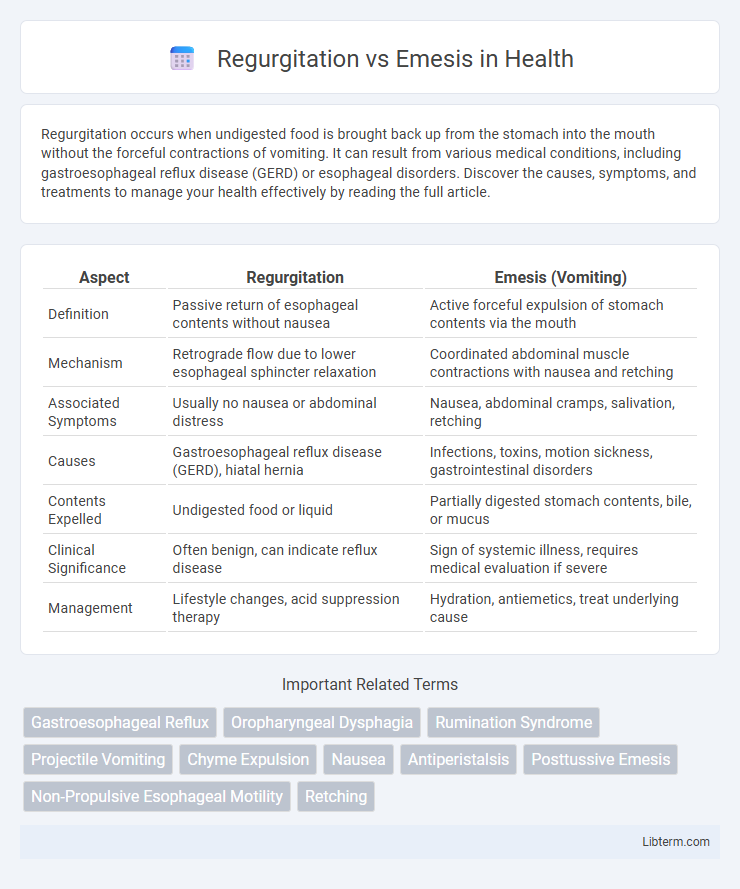

| Aspect | Regurgitation | Emesis (Vomiting) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Passive return of esophageal contents without nausea | Active forceful expulsion of stomach contents via the mouth |

| Mechanism | Retrograde flow due to lower esophageal sphincter relaxation | Coordinated abdominal muscle contractions with nausea and retching |

| Associated Symptoms | Usually no nausea or abdominal distress | Nausea, abdominal cramps, salivation, retching |

| Causes | Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hiatal hernia | Infections, toxins, motion sickness, gastrointestinal disorders |

| Contents Expelled | Undigested food or liquid | Partially digested stomach contents, bile, or mucus |

| Clinical Significance | Often benign, can indicate reflux disease | Sign of systemic illness, requires medical evaluation if severe |

| Management | Lifestyle changes, acid suppression therapy | Hydration, antiemetics, treat underlying cause |

Understanding Regurgitation and Emesis: Key Differences

Regurgitation involves the effortless, passive backflow of undigested food from the esophagus or stomach without the forceful abdominal contractions seen in emesis. Emesis, or vomiting, is an active process characterized by nausea, retching, and strong abdominal muscle contractions to expel stomach contents through the mouth. Differentiating between regurgitation and emesis is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or gastroparesis.

Medical Definitions: Regurgitation vs Emesis

Regurgitation is the passive, effortless backflow of undigested food from the esophagus or stomach into the mouth, commonly seen in infants and individuals with esophageal motility disorders. Emesis, or vomiting, is an active, reflexive process involving coordinated muscle contractions and the expulsion of stomach contents through the mouth, often triggered by gastrointestinal irritation or central nervous system stimuli. Distinguishing between regurgitation and emesis is crucial for accurate diagnosis and treatment, as regurgitation typically lacks nausea and retching, which are characteristic of emesis.

Common Causes of Regurgitation

Regurgitation commonly occurs due to esophageal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophageal motility disorders, and structural abnormalities like strictures or hiatal hernias. Unlike emesis, which involves active abdominal contractions, regurgitation is a passive process where undigested food or liquid returns to the mouth without nausea or retching. Understanding the underlying causes of regurgitation is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning in both pediatric and adult patients.

Triggers and Causes of Emesis

Emesis, commonly known as vomiting, is triggered by a complex interaction between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract, often caused by factors like infections, toxins, motion sickness, or medications that stimulate the vomiting center in the brain. Chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) activation, vestibular disturbances, and gastrointestinal irritation are primary pathways initiating emesis, differentiating it from regurgitation, which is a passive process without nausea or abdominal contractions. Understanding these triggers aids in diagnosing underlying conditions such as gastroenteritis, migraine, or drug side effects responsible for emetic episodes.

Symptoms: How to Distinguish Regurgitation from Emesis

Regurgitation involves the effortless return of undigested food or liquid from the esophagus or stomach, typically without nausea or abdominal contractions, whereas emesis is characterized by forceful expulsion of stomach contents accompanied by nausea, retching, and abdominal muscle contractions. Symptoms of regurgitation include passive spitting up of milk or food shortly after eating, often observed in infants, while emesis presents with repeated, active vomiting episodes that may include bile or blood. Recognizing the absence of nausea and retching helps distinguish regurgitation from the more intense, involuntary process of emesis.

Diagnostic Approaches: Identifying the Right Condition

Accurately distinguishing regurgitation from emesis relies on patient history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests such as upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and esophageal pH monitoring. Regurgitation typically involves passive expulsion of undigested food without nausea, while emesis is characterized by active vomiting with nausea and abdominal contractions. Radiographic studies like barium swallow can further clarify anatomical causes, enhancing diagnostic precision for targeted treatment.

Risk Factors Associated with Regurgitation and Emesis

Risk factors associated with regurgitation include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), delayed gastric emptying, and anatomical abnormalities like hiatal hernia. Emesis is commonly triggered by factors such as infections, gastrointestinal obstruction, vestibular disturbances, and the use of emetogenic drugs like chemotherapy agents. Understanding these distinct risk profiles aids in accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment strategies for each condition.

Complications and Health Risks

Regurgitation, often characterized by the effortless return of undigested food, poses risks such as aspiration pneumonia and chronic esophagitis due to frequent exposure of the esophageal lining to stomach contents. Emesis, or vomiting, involves forceful expulsion of stomach contents and can lead to severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and esophageal tears like Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Both conditions increase the risk of respiratory complications, but emesis typically presents higher immediate health risks due to its violent nature and associated systemic effects.

Treatment and Management Strategies

Regurgitation management in infants often involves feeding modifications such as smaller, frequent meals and maintaining an upright position post-feeding to reduce reflux. Emesis treatment requires addressing underlying causes like infections or gastrointestinal obstructions, with interventions ranging from antiemetic medications to, in severe cases, surgical procedures. Both conditions benefit from hydration maintenance and electrolyte balance restoration to prevent complications.

When to Seek Medical Attention for Regurgitation or Emesis

Seek medical attention for regurgitation if it occurs frequently, is accompanied by weight loss, difficulty swallowing, or persistent pain, as these symptoms may indicate underlying conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or esophageal disorders. Emesis warrants urgent care if vomiting is severe, persistent for more than 24 hours, contains blood or bile, or is associated with dehydration, high fever, or severe abdominal pain, which could signal infections, obstruction, or more serious gastrointestinal emergencies. Monitoring the frequency, content, and associated symptoms of regurgitation and emesis is crucial for timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Regurgitation Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com