Femoral hernias occur when tissue pushes through a weak spot in the muscle near the femoral vein, often causing a bulge in the upper thigh or groin area. These hernias can lead to discomfort, pain, and complications like strangulation, requiring prompt medical attention. Explore the rest of the article to understand symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options to safeguard your health.

Table of Comparison

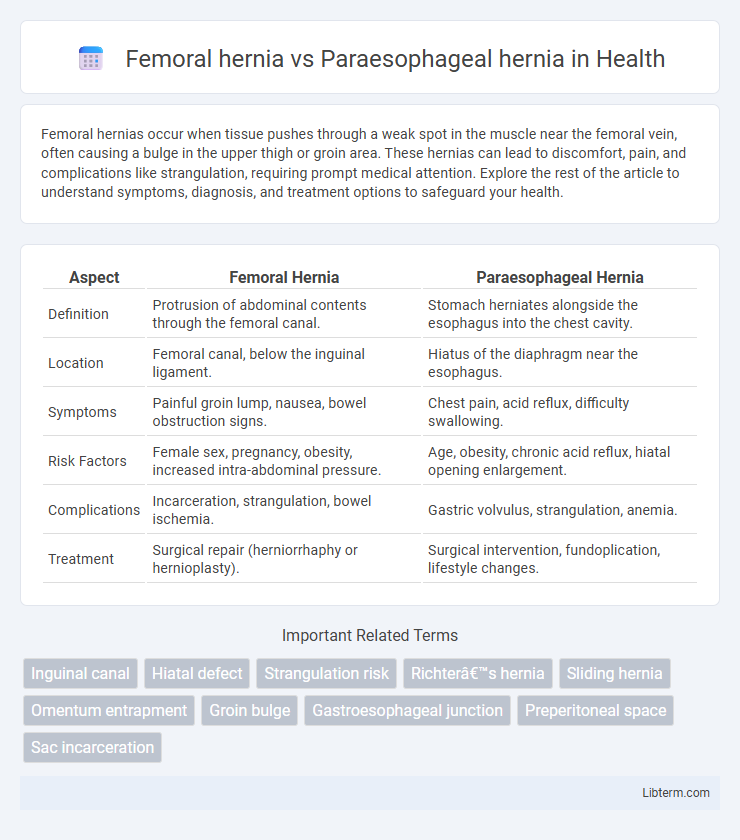

| Aspect | Femoral Hernia | Paraesophageal Hernia |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Protrusion of abdominal contents through the femoral canal. | Stomach herniates alongside the esophagus into the chest cavity. |

| Location | Femoral canal, below the inguinal ligament. | Hiatus of the diaphragm near the esophagus. |

| Symptoms | Painful groin lump, nausea, bowel obstruction signs. | Chest pain, acid reflux, difficulty swallowing. |

| Risk Factors | Female sex, pregnancy, obesity, increased intra-abdominal pressure. | Age, obesity, chronic acid reflux, hiatal opening enlargement. |

| Complications | Incarceration, strangulation, bowel ischemia. | Gastric volvulus, strangulation, anemia. |

| Treatment | Surgical repair (herniorrhaphy or hernioplasty). | Surgical intervention, fundoplication, lifestyle changes. |

Introduction to Femoral and Paraesophageal Hernias

Femoral hernias occur when tissue pushes through the femoral canal, located just below the inguinal ligament, primarily affecting women due to the wider bone structure of the female pelvis. Paraesophageal hernias involve the stomach protruding through the esophageal hiatus alongside the esophagus, posing a risk of strangulation and requiring careful monitoring. Both hernias differ in anatomical location and clinical implications, with femoral hernias commonly presenting as groin bulges and paraesophageal hernias often linked to gastroesophageal reflux symptoms.

Anatomy and Definition of Femoral Hernia

A femoral hernia occurs when abdominal tissue pushes through the femoral canal, located below the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral vein, typically presenting as a bulge near the upper thigh or groin. In contrast, a paraesophageal hernia involves the stomach herniating through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm alongside the esophagus, which can risk gastric volvulus. The femoral hernia's anatomical position makes it more common in women and prone to incarceration due to the narrow femoral canal boundaries.

Anatomy and Definition of Paraesophageal Hernia

A paraesophageal hernia occurs when part of the stomach herniates through the esophageal hiatus adjacent to the esophagus, often involving the fundus, while the gastroesophageal junction remains in its normal anatomical position. In contrast, a femoral hernia involves protrusion of abdominal contents through the femoral canal, located just below the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral vein. The paraesophageal hernia is a subtype of hiatal hernia characterized by displacement of stomach tissue into the thoracic cavity without significant upward movement of the gastroesophageal junction.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Femoral hernias are more common in older women due to increased intra-abdominal pressure from factors such as pregnancy and obesity, while paraesophageal hernias primarily affect older adults, with prevalence increasing with age and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Risk factors for femoral hernias include female gender, multiple pregnancies, and heavy lifting, whereas paraesophageal hernias are associated with hiatal hernia, obesity, and connective tissue disorders. Epidemiological data show femoral hernias constitute less than 5% of all groin hernias, whereas paraesophageal hernias represent about 5% of all hiatal hernias but carry a higher risk of complications like strangulation.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Femoral hernias typically present as a bulge or mass in the groin area, often accompanied by pain or discomfort, especially when straining or lifting, and may cause nausea or vomiting if incarcerated. Paraesophageal hernias commonly manifest with symptoms like chest pain, difficulty swallowing, and gastroesophageal reflux, but can be asymptomatic or lead to severe complications such as strangulation or obstruction. Clinical evaluation prioritizes physical examination for femoral hernias and imaging studies like barium swallow or endoscopy for paraesophageal hernias to confirm diagnosis and assess symptom severity.

Diagnostic Approaches

Femoral hernias are typically diagnosed through physical examination and ultrasound imaging to identify a bulge in the groin area, while paraesophageal hernias require advanced imaging techniques such as barium swallow studies, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and esophageal manometry to evaluate the herniated stomach and esophageal function. Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be employed for detailed visualization of paraesophageal hernias, particularly when complications like volvulus or strangulation are suspected. Accurate differentiation relies on correlating clinical symptoms with imaging findings to determine the precise anatomical location and extent of the hernia.

Complications Associated with Each Hernia

Femoral hernias often lead to complications such as incarceration and strangulation due to the narrow femoral canal, posing an urgent risk of bowel obstruction and ischemia. Paraesophageal hernias carry the risk of gastric volvulus, chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and potential strangulation of the stomach, which may cause life-threatening ischemia or perforation. Both hernias require timely diagnosis and management to prevent severe complications, with femoral hernias demanding prompt surgical intervention to avoid bowel necrosis and paraesophageal hernias necessitating careful assessment to prevent gastric compromise.

Treatment and Management Options

Femoral hernias often require prompt surgical repair due to the high risk of incarceration or strangulation, with options including open or laparoscopic herniorrhaphy tailored to patient condition and hernia size. Paraesophageal hernias typically necessitate elective surgical intervention such as laparoscopic fundoplication or mesh-reinforced hiatal repair to prevent complications like volvulus or obstruction while addressing gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Conservative management is limited to symptom control in non-surgical candidates, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and individualized treatment planning for optimal outcomes.

Prognosis and Outcomes

Femoral hernias carry a higher risk of incarceration and strangulation due to their narrow neck, leading to urgent surgical intervention and generally favorable postoperative outcomes with timely treatment. Paraesophageal hernias pose risks of gastric volvulus and ischemia, with their prognosis dependent on the severity of herniation and prompt surgical repair, often involving fundoplication to prevent recurrence. Long-term outcomes for paraesophageal hernia patients can include symptom relief and improved quality of life, while femoral hernias typically show low recurrence rates after successful surgery.

Prevention Strategies and Patient Education

Preventing femoral hernias involves maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding heavy lifting, and addressing chronic cough or constipation to reduce abdominal pressure. Paraesophageal hernia prevention emphasizes lifestyle modifications such as weight management, eating smaller meals, avoiding lying down after eating, and managing acid reflux to minimize esophageal stress. Patient education should focus on recognizing early symptoms, proper body mechanics, and the importance of medical evaluation to prevent complications associated with both hernia types.

Femoral hernia Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com