An inguinal hernia occurs when tissue, such as part of the intestine, protrudes through a weak spot in the abdominal muscles, causing a bulge in the groin area. This condition can lead to discomfort or pain, especially during physical activity or strain, and may require surgical intervention to prevent complications. Learn more about the symptoms, causes, and treatment options to protect your health and address this common issue effectively.

Table of Comparison

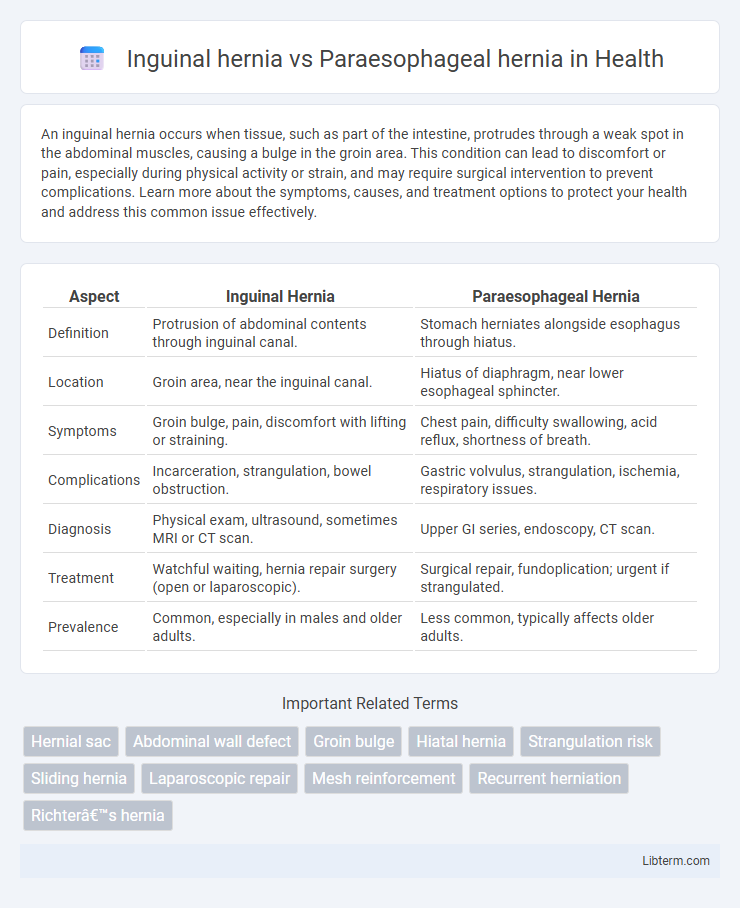

| Aspect | Inguinal Hernia | Paraesophageal Hernia |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Protrusion of abdominal contents through inguinal canal. | Stomach herniates alongside esophagus through hiatus. |

| Location | Groin area, near the inguinal canal. | Hiatus of diaphragm, near lower esophageal sphincter. |

| Symptoms | Groin bulge, pain, discomfort with lifting or straining. | Chest pain, difficulty swallowing, acid reflux, shortness of breath. |

| Complications | Incarceration, strangulation, bowel obstruction. | Gastric volvulus, strangulation, ischemia, respiratory issues. |

| Diagnosis | Physical exam, ultrasound, sometimes MRI or CT scan. | Upper GI series, endoscopy, CT scan. |

| Treatment | Watchful waiting, hernia repair surgery (open or laparoscopic). | Surgical repair, fundoplication; urgent if strangulated. |

| Prevalence | Common, especially in males and older adults. | Less common, typically affects older adults. |

Introduction to Inguinal and Paraesophageal Hernias

Inguinal hernias occur when abdominal contents protrude through the inguinal canal, predominantly affecting men and causing groin bulges and discomfort. Paraesophageal hernias involve the stomach herniating alongside the esophagus through the diaphragmatic hiatus, often leading to reflux, chest pain, or severe complications like strangulation. Understanding the anatomical differences aids in accurate diagnosis and tailored surgical intervention for these distinct hernia types.

Definition of Inguinal Hernia

An inguinal hernia occurs when tissue, such as part of the intestine, protrudes through a weak spot in the abdominal muscles near the groin area. This condition is most common in males and frequently presents as a bulge in the groin or scrotum, often causing pain or discomfort, especially during physical activity. In contrast, a paraesophageal hernia involves the stomach pushing through the diaphragm alongside the esophagus and is associated primarily with gastroesophageal reflux and risk of stomach strangulation.

Definition of Paraesophageal Hernia

A paraesophageal hernia occurs when part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm next to the esophagus, potentially causing serious complications such as strangulation or obstruction. In contrast, an inguinal hernia involves abdominal contents protruding through the inguinal canal in the groin area, primarily affecting the lower abdomen. Understanding the distinct anatomical locations and risks of these hernias is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Inguinal hernias represent the most common type of hernia, affecting approximately 27% of men and 3% of women worldwide, with risk factors including male gender, older age, chronic cough, and heavy lifting. Paraesophageal hernias, a less common subset of hiatal hernias, primarily affect older adults over 50 years due to factors such as chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), obesity, and weakened diaphragmatic muscles. Both conditions exhibit increased prevalence with advancing age but differ significantly in anatomical location and underlying risk profiles.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Inguinal hernias typically present with a visible bulge in the groin area, accompanied by discomfort or pain, especially during physical activity or straining, whereas paraesophageal hernias often cause chest pain, difficulty swallowing, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms due to stomach displacement near the esophagus. Inguinal hernias may be reducible and asymptomatic initially, while paraesophageal hernias risk strangulation and obstruction, leading to severe complications. Accurate clinical evaluation is essential to differentiate between these hernia types and guide appropriate management strategies.

Diagnostic Approaches

Inguinal hernias are primarily diagnosed through physical examination, where palpable bulges in the groin area are identified, often confirmed by ultrasound to assess hernia size and contents. Paraesophageal hernias require imaging techniques such as barium swallow radiography or upper endoscopy to visualize the herniated stomach portion alongside the esophagus. Computed tomography (CT) scans provide detailed anatomical information crucial for differentiating between these hernia types and planning surgical intervention.

Complications and Associated Risks

Inguinal hernias commonly risk incarceration and strangulation, which can lead to bowel obstruction and necrosis requiring emergency surgery. Paraesophageal hernias pose significant risks of volvulus, gastric strangulation, and chronic gastroesophageal reflux, potentially causing esophagitis, aspiration pneumonia, or Barrett's esophagus. Both conditions require timely diagnosis and appropriate surgical intervention to prevent life-threatening complications.

Treatment and Management Options

Inguinal hernia treatment primarily involves surgical repair methods such as open herniorrhaphy or laparoscopic hernia repair to prevent incarceration and strangulation. Paraesophageal hernia management often requires surgical intervention like laparoscopic hernia reduction and fundoplication to address symptoms and prevent complications such as gastric volvulus. Conservative approaches for both hernias include symptom monitoring and lifestyle modifications, but definitive treatment usually depends on hernia severity and risk of complications.

Prognosis and Long-term Outcomes

Inguinal hernia repair generally has a favorable prognosis with low recurrence rates and minimal long-term complications when timely treated, while untreated cases may lead to incarceration or strangulation, increasing morbidity. Paraesophageal hernias carry a risk of severe complications such as volvulus or gastric ischemia, necessitating surgical intervention to improve long-term outcomes and reduce mortality. Long-term follow-up for paraesophageal hernias often involves monitoring for recurrence or gastroesophageal reflux, unlike inguinal hernias where postoperative recovery is typically faster and less complex.

Prevention and Lifestyle Modifications

Inguinal hernia prevention involves maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding heavy lifting, and practicing proper lifting techniques to reduce abdominal pressure. Paraesophageal hernia prevention emphasizes weight management, eating smaller meals, avoiding foods that trigger acid reflux, and not lying down immediately after eating to minimize gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms. Both conditions benefit from quitting smoking and engaging in regular physical activity to improve overall muscle tone and digestive health.

Inguinal hernia Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com