The Doctrine of Remainders is a fundamental principle in property law that governs the future interest a person holds in real estate after the termination of a prior estate. It ensures that your property rights are clearly defined and transferred smoothly when a life estate or term of years concludes, preventing legal disputes. Explore the article further to understand how this doctrine impacts property ownership and transfers.

Table of Comparison

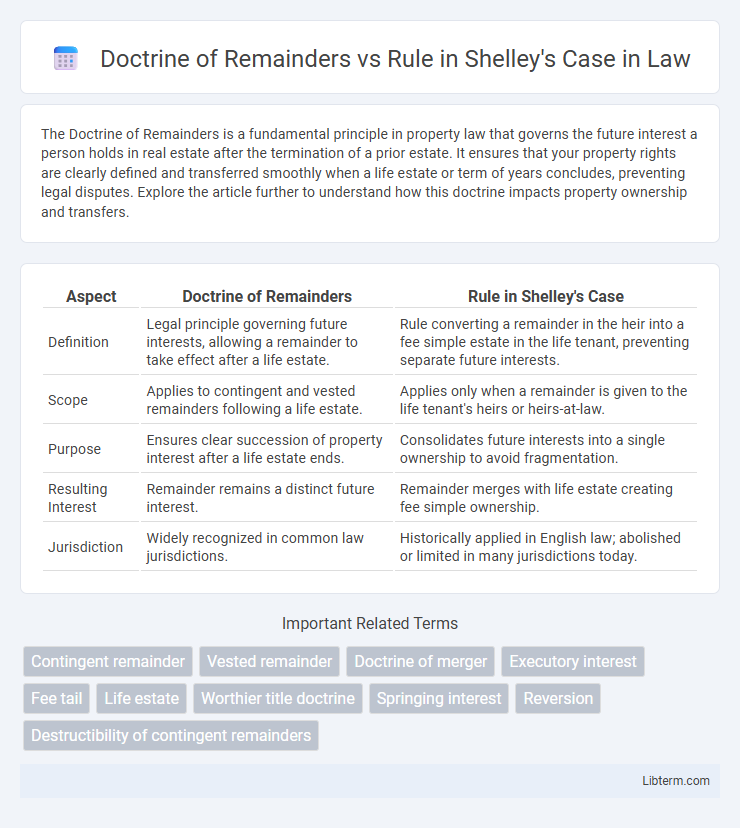

| Aspect | Doctrine of Remainders | Rule in Shelley's Case |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Legal principle governing future interests, allowing a remainder to take effect after a life estate. | Rule converting a remainder in the heir into a fee simple estate in the life tenant, preventing separate future interests. |

| Scope | Applies to contingent and vested remainders following a life estate. | Applies only when a remainder is given to the life tenant's heirs or heirs-at-law. |

| Purpose | Ensures clear succession of property interest after a life estate ends. | Consolidates future interests into a single ownership to avoid fragmentation. |

| Resulting Interest | Remainder remains a distinct future interest. | Remainder merges with life estate creating fee simple ownership. |

| Jurisdiction | Widely recognized in common law jurisdictions. | Historically applied in English law; abolished or limited in many jurisdictions today. |

Introduction to Property Law Doctrines

The Doctrine of Remainders governs future interests in property that become possessory after the expiration of a prior estate, allowing for clear transfer and succession. The Rule in Shelley's Case, an ancient common law principle, converts a remainder in a person's heirs into a vested interest in that person, simplifying inheritance. Both doctrines are fundamental in understanding property law as they determine how estates and future interests are structured and passed down.

Defining the Doctrine of Remainders

The Doctrine of Remainders governs the future interest in property that takes effect immediately after the natural termination of a prior estate, such as a life estate, without the need for any intervening event. It ensures that the remainder interest is vested or contingent, clarifying the ownership succession upon expiration of the preceding estate. This doctrine contrasts with the Rule in Shelley's Case, which merges certain future interests to create a fee simple estate, bypassing separate remainder interests.

Understanding the Rule in Shelley's Case

The Rule in Shelley's Case is a common law doctrine that converts a future interest in land held by a life tenant's heir into a fee simple estate in the tenant, preventing the creation of a remainder in the heir. This rule applies when a conveyance grants a life estate to a person and a remainder to that person's heirs, merging the interests to simplify property ownership. Understanding this rule is crucial because it overrides the Doctrine of Remainders by eliminating contingent remainders to heirs, thereby affecting estate planning and property transfers.

Historical Origins and Development

The Doctrine of Remainders originates from early English common law, evolving to regulate future interests in property and ensuring orderly succession when a life estate ends. The Rule in Shelley's Case, established in the 16th century, diverged by converting certain contingent remainders into vested estates, simplifying property transfers and avoiding fragmentation. Both doctrines significantly influenced the development of estate planning and conveyancing by addressing the complexities of future interests and inheritance.

Key Differences between Remainders and Shelley's Rule

The Doctrine of Remainders governs future interests in property that become possessory after the natural termination of prior estates, while the Rule in Shelley's Case automatically merges certain future interests to prevent the creation of successive estates. Remainders require explicitly vested interests, either vested or contingent, that follow a prior estate without cutting it short, contrasted with Shelley's Rule which converts a remainder or executory interest limited to a grantee's heirs into a fee simple estate. The key difference lies in how remainders preserve distinct future estates, whereas Shelley's Rule collapses them into a single present interest to avoid complications in inheritance and conveyancing.

Legal Significance in Modern Property Law

The Doctrine of Remainders facilitates the creation of future interests that become possessory upon the natural termination of a prior estate, enabling flexible estate planning and property transfer. In contrast, the Rule in Shelley's Case historically converted a remainder interest into a present interest, simplifying ownership but often restricting future interests. Modern property law largely favors the Doctrine of Remainders for its precision in defining and preserving distinct future interests, with the Rule in Shelley's Case abolished or limited in most jurisdictions to prevent the unintended merger of estates.

Illustrative Case Examples

The Doctrine of Remainders governs future interests in property that become possessory after the natural termination of a prior estate, exemplified in *Fletcher v. Peck* where a remainder vested in an heir after a life estate ended. In contrast, the Rule in Shelley's Case merges a remainder and a present life estate when both are held by the same person, illustrated by *Shelley v. Kraemer*, which prevented a remainder from vesting separately when granted to the same grantee's heirs. These cases highlight the critical distinction: the Doctrine allows successive ownership interests, while the Rule consolidates interests to avoid split ownership in future estates.

Statutory Reforms and Current Relevance

Statutory reforms have largely modernized the Doctrine of Remainders and the Rule in Shelley's Case, with jurisdictions like England and the United States adopting statutes that clarify or abolish the traditional complexities of these common law rules. The Rule in Shelley's Case, which merged life estates and remainder interests into a single estate, has been abolished or restricted in many jurisdictions to simplify land ownership and inheritance rights. Current relevance centers on statutory adaptations that ensure equitable property distribution and reduce litigation by explicitly defining remainder interests, making these doctrines more aligned with contemporary property law principles.

Practical Implications for Estate Planning

The Doctrine of Remainders permits the transfer of future interests to third parties, enhancing flexibility in estate planning by allowing property to pass to multiple beneficiaries sequentially. The Rule in Shelley's Case restricts this flexibility by merging the life estate and the remainder interest when granted to the same party, simplifying ownership but potentially limiting planning strategies. Understanding these doctrines is crucial for estate planners to structure interests that achieve clients' goals in asset control and tax efficiency.

Conclusion: Choosing the Appropriate Doctrine

Choosing between the Doctrine of Remainders and the Rule in Shelley's Case hinges on the specific language used in the property conveyance and the intended legal effect. The Doctrine of Remainders allows future interests to remain in third parties, promoting clarity and flexibility in estate planning, while the Rule in Shelley's Case merges life estates and remainders in the same grantee into a single vested estate, simplifying title but potentially limiting future interests. Accurate application of these doctrines depends on jurisdictional nuances and precise wording to ensure the grantor's intent is respected and property rights are clearly defined.

Doctrine of Remainders Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com