Ricardian Equivalence theory suggests that consumers anticipate future taxes resulting from government debt and adjust their savings accordingly, neutralizing the effect of fiscal policy on overall demand. This insight challenges the traditional view that deficit spending directly stimulates economic growth by highlighting the importance of expectations in financial behavior. Discover how this concept impacts economic policy and your personal financial decisions throughout the article.

Table of Comparison

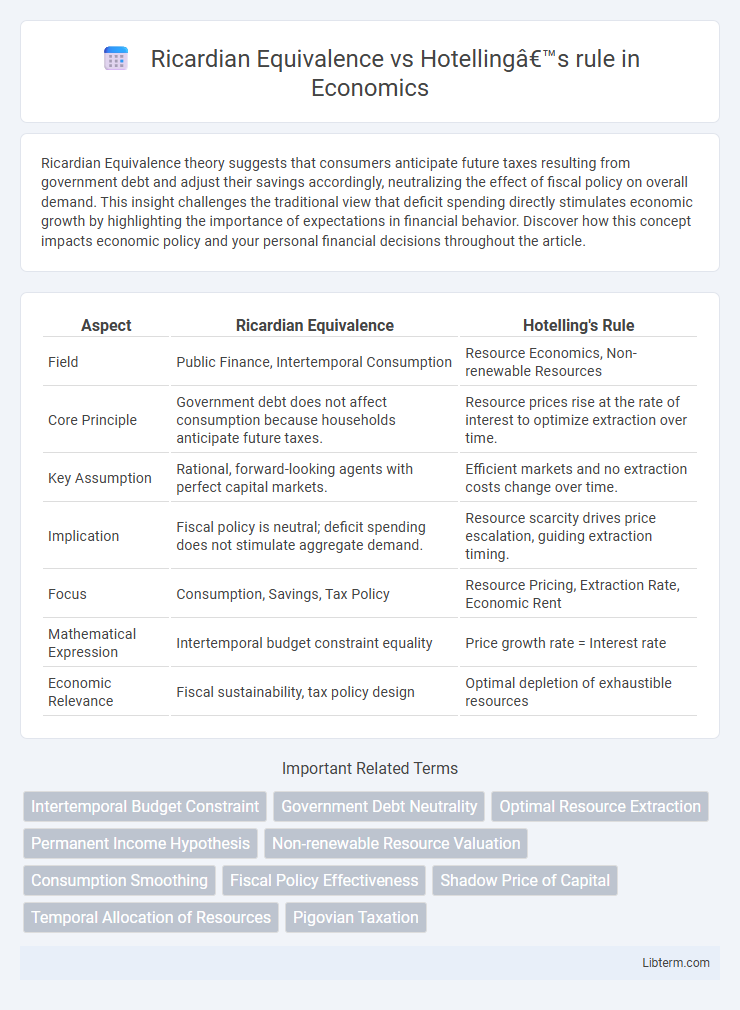

| Aspect | Ricardian Equivalence | Hotelling's Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Field | Public Finance, Intertemporal Consumption | Resource Economics, Non-renewable Resources |

| Core Principle | Government debt does not affect consumption because households anticipate future taxes. | Resource prices rise at the rate of interest to optimize extraction over time. |

| Key Assumption | Rational, forward-looking agents with perfect capital markets. | Efficient markets and no extraction costs change over time. |

| Implication | Fiscal policy is neutral; deficit spending does not stimulate aggregate demand. | Resource scarcity drives price escalation, guiding extraction timing. |

| Focus | Consumption, Savings, Tax Policy | Resource Pricing, Extraction Rate, Economic Rent |

| Mathematical Expression | Intertemporal budget constraint equality | Price growth rate = Interest rate |

| Economic Relevance | Fiscal sustainability, tax policy design | Optimal depletion of exhaustible resources |

Introduction to Ricardian Equivalence and Hotelling’s Rule

Ricardian Equivalence posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because rational consumers anticipate future taxes and adjust their savings accordingly, maintaining constant consumption over time. Hotelling's Rule, in resource economics, states that the optimal extraction rate of a non-renewable resource equates the resource's net price growth rate to the interest rate, ensuring intertemporal efficiency in resource depletion. Both concepts analyze intertemporal decision-making but apply distinct frameworks: Ricardian Equivalence addresses fiscal policy effects on consumption, while Hotelling's Rule governs the economic behavior of exhaustible resource utilization.

Historical Background and Theoretical Foundations

Ricardian Equivalence, originating from David Ricardo's early 19th-century work and formalized by Robert Barro in the 1970s, posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes. Hotelling's Rule, formulated by Harold Hotelling in 1931, provides a theory for non-renewable resource pricing, asserting resource prices must increase at the rate of interest to reflect scarcity over time. Both frameworks build on intertemporal optimization principles; Ricardian Equivalence addresses consumer behavior in fiscal policy, while Hotelling's Rule governs resource extraction and depletion economics.

Core Assumptions of Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian Equivalence assumes that consumers are forward-looking and perfectly rational, anticipating future taxes related to government debt and thus adjusting their savings accordingly to neutralize fiscal policy effects. It posits an infinite planning horizon where individuals internalize government budget constraints, implying that government borrowing does not affect overall demand. This contrasts with Hotelling's rule, which focuses on resource extraction rates and price dynamics under scarcity without emphasizing consumer intertemporal optimization or government fiscal policy.

Key Principles of Hotelling’s Rule

Hotelling's Rule states that the price of a non-renewable resource increases at the rate of interest over time, reflecting its scarcity and opportunity cost of extraction. This principle guides optimal resource extraction by balancing immediate profits against future value, ensuring intertemporal efficiency. Unlike Ricardian Equivalence, which addresses fiscal policy effects on consumption, Hotelling's Rule directly informs extraction timing and resource depletion economics.

Mathematical Formulation: Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian Equivalence is mathematically formulated through the intertemporal budget constraint, where the present value of government spending equals the present value of tax liabilities, implying consumers internalize government debt as future taxes. The core equation aligns lifetime consumption \( C_t \) with expected income and fiscal policy, expressed as \( \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \frac{C_t}{(1+r)^t} = \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \frac{Y_t - G_t}{(1+r)^t} \), where \( Y_t \) is income, \( G_t \) government spending, and \( r \) the real interest rate. This formulation ensures that a government deficit financed by debt does not affect overall demand, as rational agents anticipate future taxation to offset the debt.

Mathematical Formulation: Hotelling’s Rule

Hotelling's rule is mathematically formulated as \( \frac{dP}{dt} = rP \), where \(P\) represents the price of a non-renewable resource, \(r\) is the interest rate, and \( \frac{dP}{dt} \) is the rate of change of the resource price over time. This rule implies that the price path of exhaustible resources should grow at the rate of interest to maximize the resource owner's intertemporal profit. In contrast, Ricardian Equivalence centers on intertemporal government budget constraints without explicit pricing dynamics tied to resource extraction.

Comparative Analysis: Intertemporal Choices

Ricardian Equivalence asserts that consumers anticipate future taxes when governments increase debt, leading to unchanged consumption patterns over time since individuals save to offset expected tax burdens. Hotelling's rule governs resource extraction by dictating that non-renewable resource owners maximize profit through an intertemporal price path that increases at the rate of interest, reflecting scarcity value over time. The comparative analysis reveals Ricardian Equivalence emphasizes consumer foresight and fiscal neutrality in intertemporal choices, while Hotelling's rule concentrates on optimal depletion strategies balancing present value and future resource scarcity.

Policy Implications in Public Finance and Resource Economics

Ricardian Equivalence suggests that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes and adjust their savings, implying that deficit-financed policies may be ineffective for stimulating the economy. Hotelling's rule, governing non-renewable resource extraction, dictates that resource prices should increase at the rate of interest, guiding optimal extraction rates and informing taxation and subsidy policies to balance current exploitation with future availability. Integrating these theories, policymakers in public finance and resource economics must consider intertemporal budget constraints and resource scarcity, ensuring fiscal policies neither undermine savings behavior nor accelerate resource depletion unsustainably.

Criticisms and Limitations of Both Theories

Ricardian Equivalence faces criticism for its unrealistic assumptions of perfect capital markets and rational expectations, neglecting liquidity constraints and intergenerational wealth transfer complexities. Hotelling's rule is limited by its assumption of constant marginal extraction costs and perfect market foresight, failing to account for technological change and market imperfections. Both theories struggle with practical applicability due to idealized economic conditions and insufficient consideration of behavioral factors affecting resource extraction and fiscal policy.

Conclusion: Insights and Future Research Directions

Ricardian Equivalence highlights the neutrality of government debt on consumer behavior, while Hotelling's rule emphasizes the optimal depletion of non-renewable resources under scarcity and price dynamics. Integrating these frameworks can offer deeper insights into fiscal policy impacts on resource management and intergenerational equity. Future research should explore dynamic models combining fiscal policy with resource economics to address sustainability and long-term economic stability.

Ricardian Equivalence Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com