Pareto efficiency occurs when resources are allocated in a way that no individual can be made better off without making someone else worse off, optimizing overall economic welfare. This concept is central to evaluating the efficiency of markets and policy decisions, ensuring minimal wasted potential in resource distribution. Explore the rest of the article to understand how Pareto efficiency impacts your economic choices and societal outcomes.

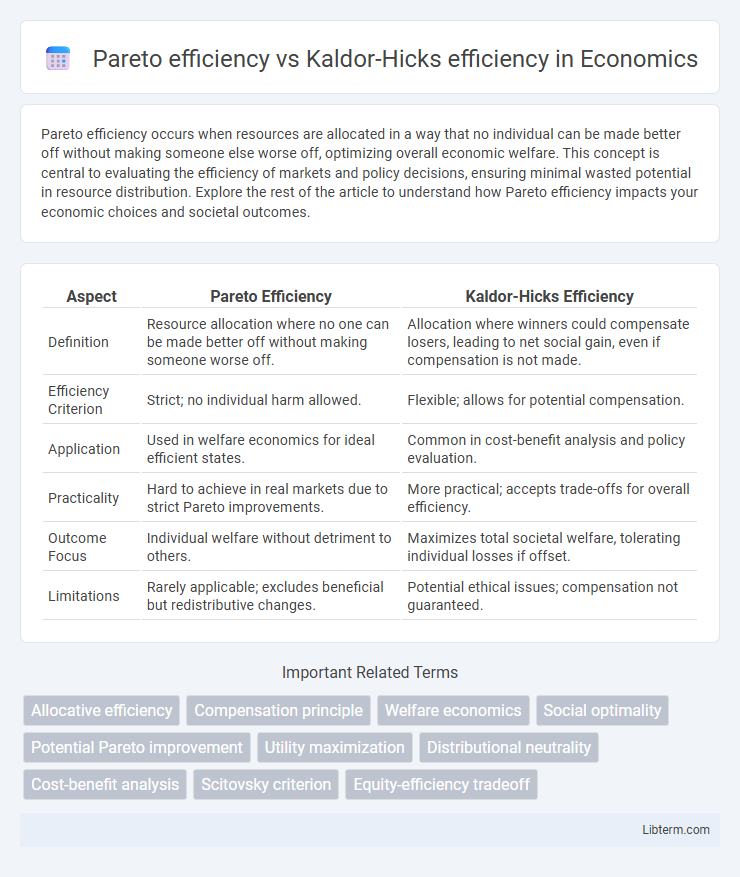

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Pareto Efficiency | Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Resource allocation where no one can be made better off without making someone worse off. | Allocation where winners could compensate losers, leading to net social gain, even if compensation is not made. |

| Efficiency Criterion | Strict; no individual harm allowed. | Flexible; allows for potential compensation. |

| Application | Used in welfare economics for ideal efficient states. | Common in cost-benefit analysis and policy evaluation. |

| Practicality | Hard to achieve in real markets due to strict Pareto improvements. | More practical; accepts trade-offs for overall efficiency. |

| Outcome Focus | Individual welfare without detriment to others. | Maximizes total societal welfare, tolerating individual losses if offset. |

| Limitations | Rarely applicable; excludes beneficial but redistributive changes. | Potential ethical issues; compensation not guaranteed. |

Introduction to Economic Efficiency

Pareto efficiency occurs when no individual can be made better off without making someone else worse off, representing an ideal allocation of resources in economics. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency allows for potential compensation, meaning an outcome is efficient if those who benefit could theoretically compensate those who lose out, even if compensation does not actually happen. These concepts are fundamental in evaluating economic policies and resource distribution, balancing optimality and practical trade-offs in welfare economics.

Defining Pareto Efficiency

Pareto efficiency occurs when no individual's situation can be improved without worsening another's, establishing an optimal resource allocation with no possible gains from trade. This concept emphasizes mutually beneficial outcomes where reallocations cannot enhance overall welfare without causing harm. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency differs by allowing improvements if winners could theoretically compensate losers, even if compensation is not actualized.

Understanding Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency

Kaldor-Hicks efficiency improves upon Pareto efficiency by allowing outcomes where some individuals can be better off even if others are worse off, as long as the winners could hypothetically compensate the losers. This concept prioritizes overall economic efficiency by assessing whether the total benefits exceed total costs, without requiring all parties to be made better off simultaneously. Understanding Kaldor-Hicks efficiency is crucial for policy analysis and cost-benefit evaluations where redistributive compensation isn't mandatory but potential gains justify changes.

Key Differences Between Pareto and Kaldor-Hicks

Pareto efficiency occurs when no individual can be made better off without making someone else worse off, representing an allocation where resources are optimally distributed without harm; Kaldor-Hicks efficiency allows for compensation where winners could theoretically compensate losers, enabling changes that increase overall welfare even if some individuals lose. Key differences include Pareto efficiency's strict requirement for no losers, while Kaldor-Hicks efficiency accepts potential losers as long as the net benefits outweigh the costs, making it more flexible for policy analysis and cost-benefit evaluation. Pareto efficiency is often seen as a benchmark for equity, whereas Kaldor-Hicks efficiency prioritizes maximizing total social surplus despite distributional inequities.

Criteria for Assessing Efficiency in Economics

Pareto efficiency is achieved when no individual can be made better off without making someone else worse off, emphasizing strict equity in resource allocation. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency allows for potential compensation, where an allocation is efficient if those that benefit could theoretically compensate those that lose out, even if compensation does not occur. These criteria assess economic efficiency by balancing strict Pareto improvements with practical considerations of potential welfare gains.

Real-world Examples of Pareto Improvements

Pareto improvements occur when a change benefits at least one individual without making anyone worse off, exemplified by technology advancements increasing productivity without job losses, and urban planning projects that enhance public transportation without reducing service quality. For instance, a company implementing energy-efficient machinery can reduce operational costs and pollution, benefiting both the business and community without detriment to employees. Similarly, trade agreements that expand market access while preserving existing welfare levels for all parties demonstrate tangible Pareto improvements in real-world economics.

Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency in Policy Analysis

Kaldor-Hicks efficiency is a key criterion in policy analysis, assessing whether the benefits of a policy exceed its costs, allowing winners to potentially compensate losers even if compensation does not occur. Unlike Pareto efficiency, which requires no one to be worse off, Kaldor-Hicks efficiency accepts potential trade-offs to achieve greater overall social welfare. This approach enables policymakers to evaluate projects with net positive impacts, supporting decisions in cost-benefit analysis and economic optimization.

Limitations of Pareto and Kaldor-Hicks Criteria

Pareto efficiency is limited by its strict requirement that no individual's well-being can be worsened, making it impractical for policy decisions where trade-offs are necessary. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency addresses this by allowing outcomes where losers could theoretically be compensated, but its limitation lies in ignoring actual compensation and distributional equity, often overlooking winners' ability or willingness to compensate losers. Both criteria fail to fully account for fairness and real-world complexities, complicating their application in economic and social policy evaluations.

Implications for Welfare Economics

Pareto efficiency requires that no individual can be made better off without making someone else worse off, establishing a strict criterion for welfare improvement that limits policy interventions. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency allows for potential compensation where winners gain enough to theoretically offset the losses of others, expanding the scope of welfare-improving policies even if actual compensation does not occur. This distinction influences welfare economics by prioritizing actual vs. potential improvements, shaping debates on fairness, policy feasibility, and social welfare optimization.

Choosing the Right Efficiency Concept

Choosing the right efficiency concept depends on the context of the economic analysis, where Pareto efficiency requires no individual to be worse off after a change, emphasizing unanimous gain, while Kaldor-Hicks efficiency allows for potential compensation, focusing on an overall increase in net benefits. Pareto efficiency is ideal for scenarios demanding strict fairness without any losers, whereas Kaldor-Hicks is more practical for policy decisions involving trade-offs and potential redistribution. Understanding these distinctions aids in selecting the appropriate criterion to evaluate welfare improvements and resource allocation effectively.

Pareto efficiency Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com