Classical unemployment occurs when wages are set above the market-clearing level, leading to a surplus of labor and unfilled job vacancies. This type of unemployment often results from minimum wage laws, labor unions, or other wage rigidities that prevent the labor market from adjusting to supply and demand. Discover the causes and potential solutions to classical unemployment as you explore the rest of this article.

Table of Comparison

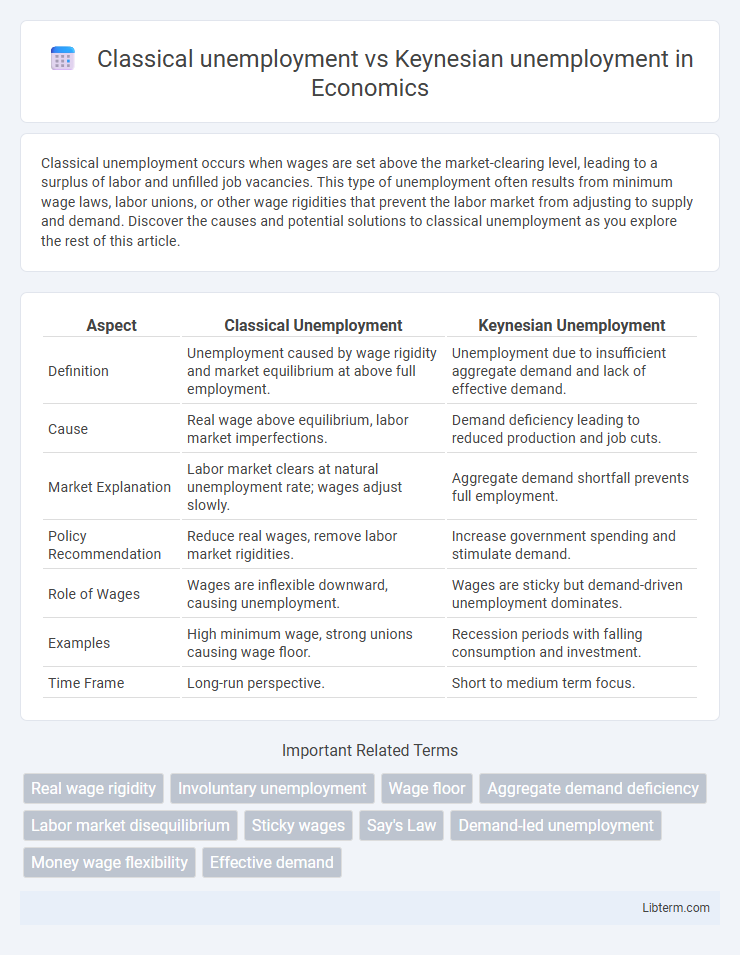

| Aspect | Classical Unemployment | Keynesian Unemployment |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Unemployment caused by wage rigidity and market equilibrium at above full employment. | Unemployment due to insufficient aggregate demand and lack of effective demand. |

| Cause | Real wage above equilibrium, labor market imperfections. | Demand deficiency leading to reduced production and job cuts. |

| Market Explanation | Labor market clears at natural unemployment rate; wages adjust slowly. | Aggregate demand shortfall prevents full employment. |

| Policy Recommendation | Reduce real wages, remove labor market rigidities. | Increase government spending and stimulate demand. |

| Role of Wages | Wages are inflexible downward, causing unemployment. | Wages are sticky but demand-driven unemployment dominates. |

| Examples | High minimum wage, strong unions causing wage floor. | Recession periods with falling consumption and investment. |

| Time Frame | Long-run perspective. | Short to medium term focus. |

Introduction to Classical and Keynesian Unemployment

Classical unemployment occurs when wages are rigid above the equilibrium level, causing labor supply to exceed demand, often due to minimum wage laws or union activities. Keynesian unemployment arises from insufficient aggregate demand, leading to involuntary joblessness despite flexible wages. Understanding these types highlights the contrasting roles of wage flexibility and demand in labor market dynamics.

Defining Unemployment: Classical vs Keynesian Perspectives

Classical unemployment occurs when wages are rigid above the equilibrium level, causing labor supply to exceed demand and resulting in involuntary joblessness. Keynesian unemployment arises from insufficient aggregate demand, leading to layoffs even when wages are flexible and labor markets should clear. The Classical perspective emphasizes wage-price flexibility as a solution, while the Keynesian view advocates for government intervention to boost demand and reduce unemployment.

Origins and Historical Background

Classical unemployment originates from early 19th-century economic theories emphasizing wage rigidity and market self-regulation, with economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo advocating that labor markets clear when wages adjust freely. Keynesian unemployment emerged during the Great Depression of the 1930s, rooted in John Maynard Keynes's critique of classical economics, highlighting insufficient aggregate demand as the primary cause of prolonged unemployment. The historical shift from classical to Keynesian thought marked a transformative period in macroeconomic policy, promoting government intervention to stabilize employment levels.

Classical Unemployment: Causes and Mechanisms

Classical unemployment arises primarily from real wage rigidity, where wages remain above equilibrium due to minimum wage laws, labor unions, or efficiency wages, causing excess labor supply. This type of unemployment is driven by market imbalances where the labor market fails to clear because wages do not adjust downward to reflect labor demand. Key mechanisms include wage stickiness and structural mismatches, leading to persistent joblessness even when job vacancies exist.

Keynesian Unemployment: Causes and Mechanisms

Keynesian unemployment arises from insufficient aggregate demand in the economy, causing reduced production and job losses despite available labor. It occurs when consumer spending, investment, or government expenditure declines, leading to a demand deficit that classical wage adjustments cannot quickly remedy. This form of unemployment highlights the importance of fiscal and monetary policies to stimulate demand and restore full employment.

Role of Wages in Unemployment Theories

Classical unemployment theory argues that unemployment results from wages being set above the equilibrium level, causing a surplus of labor as firms reduce hiring. Keynesian unemployment emphasizes that wages are often sticky downward, preventing labor market adjustments and leading to persistent unemployment even when demand is insufficient. Wage rigidity in Keynesian models contributes to prolonged unemployment by hindering the natural clearing of labor markets predicted by classical economics.

Government Intervention: Classical vs Keynesian View

Classical unemployment arises from wages set above equilibrium, leading to labor surplus, where government intervention in wage control is generally discouraged to allow market self-correction. Keynesian unemployment results from insufficient aggregate demand causing inadequate job creation, prompting active government policies like fiscal stimulus and public spending to boost demand and reduce unemployment. The Keynesian approach supports intervention to stabilize the economy, while the Classical approach favors minimal interference, emphasizing flexible wages and market adjustments.

Labor Market Dynamics and Policy Implications

Classical unemployment arises from wage rigidities and market imbalances where real wages exceed equilibrium, causing labor supply to surpass demand, leading to persistent joblessness. Keynesian unemployment occurs due to insufficient aggregate demand, resulting in involuntary unemployment despite flexible wages, highlighting the role of demand-side fluctuations in labor market dynamics. Policy implications for Classical unemployment emphasize labor market flexibility and deregulation, while Keynesian unemployment requires fiscal stimulus and demand management to boost employment.

Real-World Examples: Classical vs Keynesian Unemployment

Classical unemployment occurs when wages are rigid above the equilibrium level, often caused by minimum wage laws or labor unions, as seen in the post-war European economies where wage floors limited job creation. Keynesian unemployment arises from insufficient aggregate demand, exemplified by the Great Depression in the 1930s when massive job losses stemmed from reduced consumer spending and investment. Modern examples include Japan's persistent Keynesian unemployment tied to stagnant demand, contrasting with certain Latin American countries where structural wage rigidity reflects classical unemployment patterns.

Conclusion: Comparative Analysis and Future Outlook

Classical unemployment arises from wage rigidities and market inflexibilities, while Keynesian unemployment stems from insufficient aggregate demand causing labor underutilization. Empirical studies highlight Keynesian theories' effectiveness during economic downturns, emphasizing demand-stimulation policies, whereas Classical views dominate in long-term labor market adjustments prioritizing supply-side mechanisms. Future outlooks suggest hybrid approaches integrating wage flexibility with demand management enhance unemployment reduction amid evolving global economic structures.

Classical unemployment Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com