Behavioral economics explores how psychological factors influence economic decision-making, challenging traditional models based on rational choice. It examines biases, heuristics, and emotions that shape consumer behavior and market outcomes. Discover how understanding these concepts can improve Your financial decisions by reading the full article.

Table of Comparison

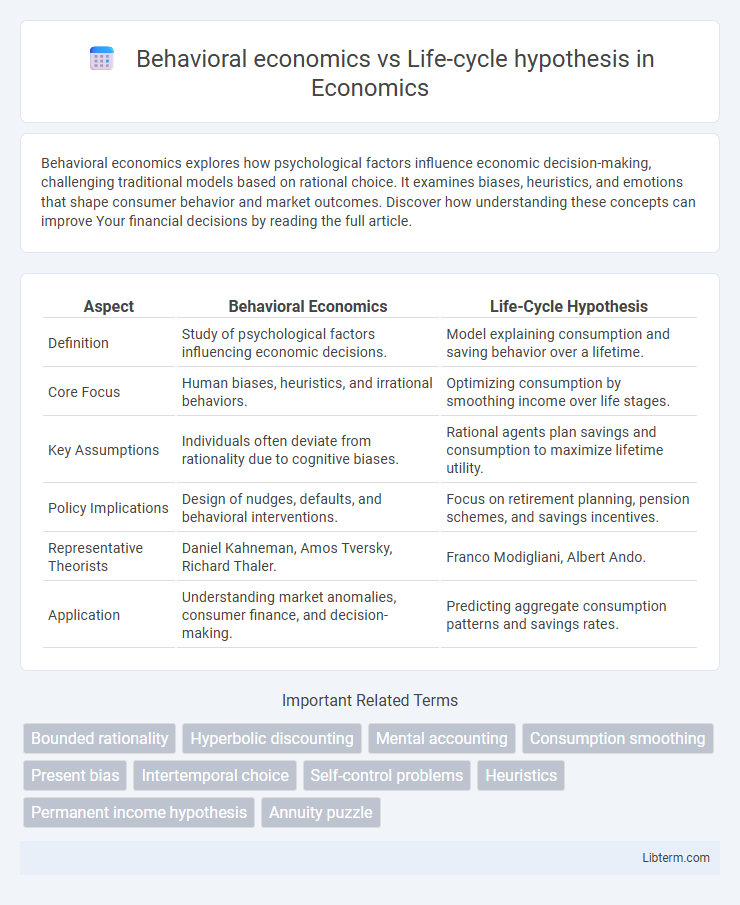

| Aspect | Behavioral Economics | Life-Cycle Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Study of psychological factors influencing economic decisions. | Model explaining consumption and saving behavior over a lifetime. |

| Core Focus | Human biases, heuristics, and irrational behaviors. | Optimizing consumption by smoothing income over life stages. |

| Key Assumptions | Individuals often deviate from rationality due to cognitive biases. | Rational agents plan savings and consumption to maximize lifetime utility. |

| Policy Implications | Design of nudges, defaults, and behavioral interventions. | Focus on retirement planning, pension schemes, and savings incentives. |

| Representative Theorists | Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Richard Thaler. | Franco Modigliani, Albert Ando. |

| Application | Understanding market anomalies, consumer finance, and decision-making. | Predicting aggregate consumption patterns and savings rates. |

Introduction to Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics challenges traditional economic assumptions by integrating psychological insights into decision-making, highlighting how cognitive biases, emotions, and social factors influence consumer behavior. Unlike the Life-cycle Hypothesis, which predicts stable, rational consumption patterns over a lifetime based on income smoothing, behavioral economics accounts for anomalies such as present bias and mental accounting that disrupt optimal saving and spending. This approach provides a richer understanding of economic choices, emphasizing real-world deviations from perfectly rational models.

Overview of the Life-Cycle Hypothesis

The Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) explains individual consumption and saving patterns based on predictable life stages, suggesting that people plan their finances to smooth consumption over their lifetime. Behavioral economics challenges this rational model by incorporating psychological factors like present bias, limited self-control, and heuristics, which cause deviations from the optimal savings predicted by LCH. The LCH assumes forward-looking rationality, while behavioral economics accounts for observed inconsistencies in actual financial behavior, emphasizing the gap between theoretical consumption models and real-world decision-making.

Key Principles of Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics emphasizes cognitive biases, such as loss aversion and mental accounting, which influence individuals' decision-making processes and deviate from rational economic behavior. It highlights bounded rationality, framing effects, and time-inconsistent preferences that lead to systematic errors in saving and spending patterns. In contrast, the Life-cycle hypothesis assumes rational planning and optimization of consumption over a lifetime, focusing on income smoothing and predictable financial behavior.

Core Assumptions of the Life-Cycle Hypothesis

The Life-Cycle Hypothesis assumes individuals plan their consumption and savings behavior over their lifetime to smooth consumption by accumulating assets during working years and decumulating during retirement. It posits rational expectations and foresight, with consumers optimizing intertemporal utility based on predictable income patterns. Unlike behavioral economics, which incorporates psychological biases and heuristics affecting decisions, the Life-Cycle Hypothesis relies on normative, utility-maximizing behavior across different life stages.

Contrasting Rationality: Theory vs. Reality

Behavioral economics challenges the life-cycle hypothesis by highlighting systematic deviations from rational decision-making, such as present bias and mental accounting, which cause individuals to inconsistently plan and save over their lifetime. The life-cycle hypothesis assumes rational agents optimize consumption and savings smoothly based on lifetime income, but behavioral economics reveals real-world cognitive limitations and emotional influences disrupting this model. Empirical studies demonstrate that these behavioral factors result in savings patterns that deviate significantly from the life-cycle predictions, underscoring the gap between theoretical rationality and actual financial behavior.

Psychological Biases in Economic Decision-Making

Behavioral economics highlights how psychological biases, such as overconfidence and present bias, systematically distort economic decision-making and lead to deviations from rational models. The Life-cycle hypothesis assumes individuals optimize consumption and saving over their lifetime, but behavioral biases often cause inconsistent saving patterns and underpreparedness for retirement. Recognizing these cognitive limitations improves the design of financial policies and interventions aimed at enhancing long-term economic well-being.

Strengths and Limitations of the Life-Cycle Hypothesis

The Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) provides a robust framework for understanding consumer saving and spending patterns over a lifetime, emphasizing income smoothing and consumption optimization from youth to retirement. Its strength lies in modeling predictable variations in consumption based on age-related income changes, but limitations include insufficient consideration of behavioral biases such as self-control problems and myopia addressed by behavioral economics. Furthermore, LCH assumes perfect foresight and rational planning, which often contrasts with empirical findings showing deviations due to psychological factors and uncertainty in income and lifespan.

Behavioral Insights on Consumption and Savings

Behavioral economics highlights how cognitive biases, such as hyperbolic discounting and loss aversion, influence consumers to deviate from the rational decision-making predicted by the Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH), leading to suboptimal savings and consumption patterns. Unlike the LCH, which assumes individuals plan consumption smoothly over their lifetime based on expected income, behavioral insights reveal tendencies for impulsive spending and insufficient retirement savings. These findings emphasize the need for policy interventions like commitment devices and nudges to improve financial well-being by counteracting behavioral biases.

Empirical Evidence: Real-World Applications

Behavioral economics provides empirical evidence showing that individuals often deviate from the optimal saving patterns predicted by the Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) due to biases such as present bias and limited self-control. Studies reveal that real-world savings behavior frequently reflects anomalies like procrastination and under-saving for retirement, challenging the LCH's assumption of rational, forward-looking agents. Experimental data and field studies demonstrate how behavioral interventions, such as automatic enrollment in pension plans, improve savings outcomes more effectively than traditional LCH-based models.

Implications for Policy and Personal Finance

Behavioral economics challenges the Life-cycle hypothesis by highlighting systematic cognitive biases and heuristics that lead individuals to deviate from optimal consumption and saving patterns, suggesting policies that incorporate nudges and default options. Life-cycle hypothesis assumes rational planning over a lifetime, supporting policies that promote long-term savings through tax incentives and retirement accounts. Incorporating behavioral insights can improve personal finance strategies by addressing procrastination, overconfidence, and impulsivity, leading to enhanced financial well-being and more effective retirement planning.

Behavioral economics Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com