Sliding hernia occurs when an organ, such as the colon or bladder, forms part of the hernia sac and slides into the groin or abdominal wall. This type of hernia can complicate diagnosis and treatment because the organ itself is involved in the herniation, increasing risks during surgical repair. Explore the rest of this article to understand symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options for your sliding hernia.

Table of Comparison

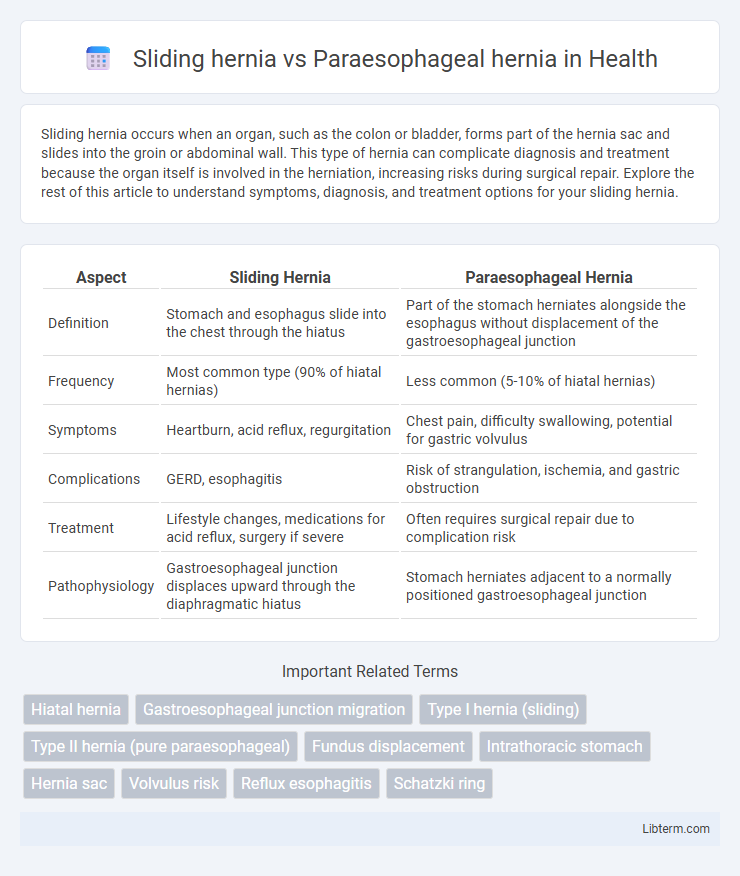

| Aspect | Sliding Hernia | Paraesophageal Hernia |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Stomach and esophagus slide into the chest through the hiatus | Part of the stomach herniates alongside the esophagus without displacement of the gastroesophageal junction |

| Frequency | Most common type (90% of hiatal hernias) | Less common (5-10% of hiatal hernias) |

| Symptoms | Heartburn, acid reflux, regurgitation | Chest pain, difficulty swallowing, potential for gastric volvulus |

| Complications | GERD, esophagitis | Risk of strangulation, ischemia, and gastric obstruction |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medications for acid reflux, surgery if severe | Often requires surgical repair due to complication risk |

| Pathophysiology | Gastroesophageal junction displaces upward through the diaphragmatic hiatus | Stomach herniates adjacent to a normally positioned gastroesophageal junction |

Overview of Hiatal Hernias

Hiatal hernias occur when part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm into the chest cavity, with two main types being sliding hernias and paraesophageal hernias. Sliding hernias account for approximately 95% of hiatal hernias, characterized by the stomach and the gastroesophageal junction sliding upward into the thorax, often resulting in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Paraesophageal hernias, less common but potentially more serious, involve part of the stomach herniating alongside the esophagus without displacement of the gastroesophageal junction, increasing the risk of strangulation and requiring surgical intervention.

Defining Sliding Hernia

Sliding hernia, the most common type of hiatal hernia, occurs when the stomach and part of the esophagus slide up into the chest through the diaphragmatic esophageal hiatus. In contrast, a paraesophageal hernia involves the stomach herniating alongside the esophagus without displacement of the gastroesophageal junction. Sliding hernias often cause gastroesophageal reflux due to the disrupted anatomy, whereas paraesophageal hernias pose risks of strangulation and require more urgent surgical intervention.

Defining Paraesophageal Hernia

Paraesophageal hernia occurs when part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm beside the esophagus, distinct from the more common sliding hernia where the stomach and esophageal junction move upward. This type of hernia can lead to complications such as strangulation or obstruction, requiring careful medical evaluation. Unlike sliding hernias, which often cause gastroesophageal reflux, paraesophageal hernias may not produce reflux but present with chest pain or difficulty swallowing.

Key Differences: Sliding vs Paraesophageal Hernia

Sliding hernias involve the stomach and the lower esophageal sphincter sliding up into the chest through the esophageal hiatus, making them the most common type of hiatal hernia. Paraesophageal hernias occur when part of the stomach pushes through the diaphragm next to the esophagus, potentially causing more severe complications like strangulation or obstruction. Unlike sliding hernias, paraesophageal hernias require careful monitoring or surgical intervention due to the increased risk of serious symptoms and complications.

Causes and Risk Factors

Sliding hernias primarily result from the weakening of the diaphragm's esophageal hiatus, often caused by age-related muscle degeneration, obesity, or chronic increased abdominal pressure such as from coughing or heavy lifting. Paraesophageal hernias arise when the stomach herniates alongside the esophagus through a defect in the diaphragm, frequently linked to congenital anatomical abnormalities or trauma. Risk factors for both conditions include obesity, smoking, and chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which contribute to increased intra-abdominal pressure and weakened diaphragmatic structures.

Clinical Symptoms Comparison

Sliding hernias typically present with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, and chest discomfort due to the upward movement of the stomach through the diaphragmatic hiatus. Paraesophageal hernias often cause more severe clinical symptoms including chronic chest pain, dysphagia, and early satiety because the stomach herniates alongside the esophagus without reflux, increasing the risk of strangulation and gastric obstruction. Symptom severity and complication risk are generally higher in paraesophageal hernias compared to sliding hernias, necessitating distinct clinical management strategies.

Complications and Risks

Sliding hernias primarily involve the stomach and the lower esophagus moving into the chest, commonly causing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with risks of esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus. Paraesophageal hernias carry a higher risk of serious complications such as strangulation, volvulus, and ischemia due to the stomach herniating alongside the esophagus while the gastroesophageal junction remains fixed. Surgical intervention is often required for paraesophageal hernias to prevent life-threatening outcomes, whereas sliding hernias are usually managed conservatively unless severe complications arise.

Diagnostic Methods and Tests

Sliding hernias are typically diagnosed through barium swallow radiographs and upper endoscopy, which reveal the upward displacement of the gastroesophageal junction into the thoracic cavity. Paraesophageal hernias require computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for detailed visualization of the herniated stomach alongside the esophagus. Esophageal manometry and pH monitoring also support differential diagnosis by assessing esophageal motility and acid reflux patterns characteristic to each hernia type.

Treatment Options for Each Type

Sliding hernias are commonly treated with lifestyle modifications and acid-suppressing medications such as proton pump inhibitors, while surgical intervention like laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is recommended when symptoms persist or complications arise. Paraesophageal hernias often require surgical repair due to the risk of complications like strangulation or obstruction, typically involving hernia reduction, crural repair, and fundoplication. Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery is preferred for both types, offering shorter recovery times and reduced postoperative pain.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

Sliding hernias, which involve the gastroesophageal junction moving above the diaphragm, generally have a favorable prognosis with effective management through lifestyle modifications and proton pump inhibitors, though recurrence is possible after surgical repair. Paraesophageal hernias, characterized by the stomach herniating alongside the esophagus while the gastroesophageal junction remains in place, carry a higher risk of complications such as strangulation and require surgical intervention to prevent severe outcomes. Long-term outcomes for paraesophageal hernias depend heavily on timely surgical repair, with delayed treatment increasing morbidity and mortality risks compared to sliding hernias, which more commonly present with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and exhibit better post-treatment quality of life.

Sliding hernia Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com