Latent refers to something that exists but remains hidden or inactive until triggered or revealed. Understanding latent traits or conditions can unlock new potential in various fields such as psychology, technology, and biology. Explore the rest of this article to uncover how latent factors impact your world and decision-making.

Table of Comparison

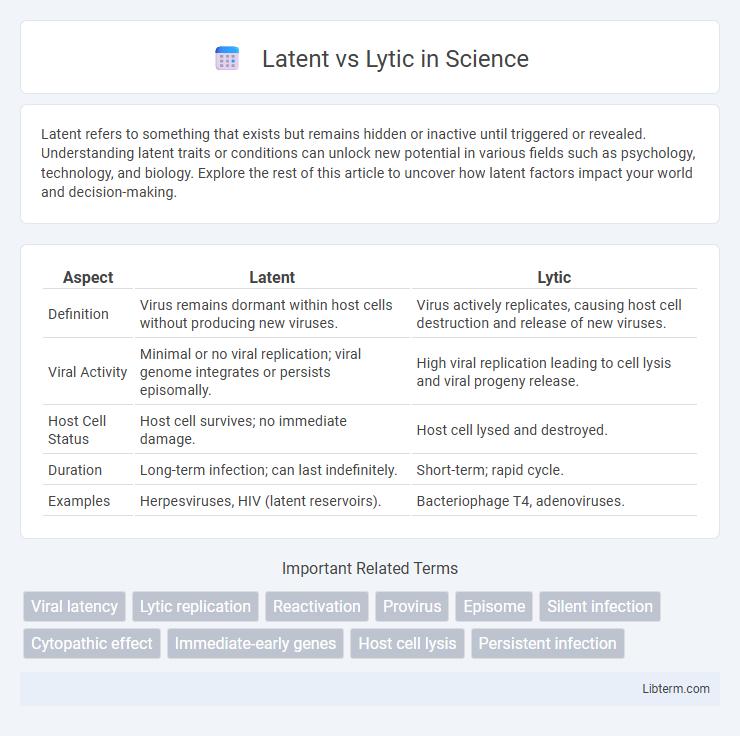

| Aspect | Latent | Lytic |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Virus remains dormant within host cells without producing new viruses. | Virus actively replicates, causing host cell destruction and release of new viruses. |

| Viral Activity | Minimal or no viral replication; viral genome integrates or persists episomally. | High viral replication leading to cell lysis and viral progeny release. |

| Host Cell Status | Host cell survives; no immediate damage. | Host cell lysed and destroyed. |

| Duration | Long-term infection; can last indefinitely. | Short-term; rapid cycle. |

| Examples | Herpesviruses, HIV (latent reservoirs). | Bacteriophage T4, adenoviruses. |

Introduction to Latent and Lytic Cycles

The latent and lytic cycles describe two distinct phases of viral replication in host cells. The latent cycle involves the integration of viral DNA into the host genome, allowing the virus to remain dormant without producing new virions. In contrast, the lytic cycle triggers active replication, leading to the production of new virus particles and eventual lysis of the infected cell.

Defining the Latent Cycle

The latent cycle in viral infections involves the virus integrating its genome into the host cell without producing new virions, allowing it to remain dormant for extended periods. During latency, viral genes necessary for replication are largely suppressed, evading the host immune response and preventing cell lysis. This contrasts with the lytic cycle, where active viral replication leads to host cell destruction and release of progeny viruses.

Understanding the Lytic Cycle

The lytic cycle involves the rapid replication of viruses within a host cell, culminating in the host's destruction and the release of new viral particles. Key stages include viral attachment, penetration, biosynthesis of viral components, assembly of virions, and cell lysis. Understanding the lytic cycle is crucial for developing antiviral therapies targeting viral replication and preventing the spread of infection.

Key Differences Between Latent and Lytic Infections

Latent infections involve viral genomes persisting in host cells without producing new viruses, often remaining dormant for extended periods, while lytic infections actively replicate viruses, resulting in host cell destruction. Key differences include latency's characteristic minimal viral gene expression and lack of symptoms during dormancy, versus lytic infections causing rapid cell lysis and symptomatic disease. Understanding these differences is critical for developing targeted antiviral therapies and managing chronic versus acute viral diseases.

Molecular Mechanisms of Latency

Latent viral infections involve the suppression of active viral replication through molecular mechanisms such as chromatin remodeling, transcriptional repression by latency-associated transcripts (LATs), and epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation and histone deacetylation. Viral genomes integrate into host DNA or persist episomally, maintaining a dormant state by silencing lytic gene expression and preventing immune detection. Reactivation triggers signaling pathways that alter these molecular controls, shifting the virus from latency to active lytic replication.

Triggers for Lytic Reactivation

Triggers for lytic reactivation in herpesviruses include cellular stress, immunosuppression, and exposure to ultraviolet light. Chemical agents such as phorbol esters and histone deacetylase inhibitors can also induce the switch from latency to the lytic cycle. Viral gene expression is altered by these triggers, leading to the activation of immediate-early genes essential for viral replication.

Examples of Latent and Lytic Viruses

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are prime examples of latent viruses that can remain dormant within host cells, reactivating under certain conditions. Influenza virus and adenovirus exemplify lytic viruses, where infection results in rapid replication and cell destruction. Understanding the distinct cycles of latent and lytic viruses aids in developing targeted antiviral therapies for diseases like cold sores, mononucleosis, and flu.

Clinical Implications of Latency and Lytic Activation

Latent viral infections, characterized by dormancy within host cells, pose significant challenges for clinical management due to their ability to evade immune detection and establish lifelong persistence, often leading to periodic reactivation events. Lytic activation triggers active viral replication and cell destruction, manifesting in acute symptoms and requiring targeted antiviral therapies to mitigate tissue damage and systemic spread. Understanding latency mechanisms and lytic cycles is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies to prevent reactivation, manage chronic disease progression, and improve patient outcomes in infections such as herpesviruses and HIV.

Diagnostic Approaches for Latent vs Lytic Infections

Diagnostic approaches for latent infections primarily rely on molecular techniques such as PCR to detect viral DNA within host cells, highlighting the presence of dormant viruses without active replication. In contrast, lytic infections are typically identified through assays that detect viral replication markers, including antigen detection, viral culture, and serological tests measuring active antibody responses. Imaging and cytopathic effect observations further support diagnosis by revealing tissue damage and cell lysis characteristic of lytic infection stages.

Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Latent and Lytic Phases

Therapeutic strategies targeting latent and lytic phases of viral infections focus on either reactivating latent viruses to expose them to antiviral agents or directly inhibiting lytic replication to prevent viral proliferation. Latency-reversing agents (LRAs) such as histone deacetylase inhibitors are used to disrupt viral latency, enabling immune clearance or antiviral drug action. For the lytic phase, antiviral drugs targeting viral DNA polymerase or protease enzymes reduce viral load and limit tissue damage during active infection.

Latent Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com