A Kaldor-Hicks improvement occurs when the benefits to winners from a policy change exceed the losses to those worse off, allowing for potential compensation despite no actual compensation taking place. This concept is widely used in cost-benefit analysis to evaluate whether economic changes lead to overall efficiency gains. Explore the article to understand how Kaldor-Hicks improvements influence decision-making and economic policy.

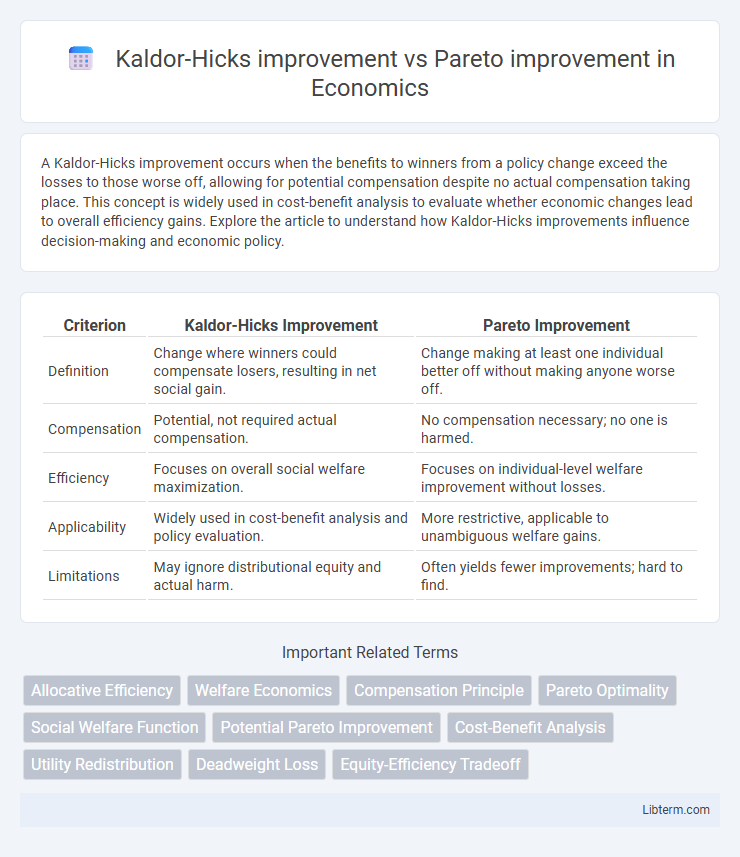

Table of Comparison

| Criterion | Kaldor-Hicks Improvement | Pareto Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Change where winners could compensate losers, resulting in net social gain. | Change making at least one individual better off without making anyone worse off. |

| Compensation | Potential, not required actual compensation. | No compensation necessary; no one is harmed. |

| Efficiency | Focuses on overall social welfare maximization. | Focuses on individual-level welfare improvement without losses. |

| Applicability | Widely used in cost-benefit analysis and policy evaluation. | More restrictive, applicable to unambiguous welfare gains. |

| Limitations | May ignore distributional equity and actual harm. | Often yields fewer improvements; hard to find. |

Introduction to Economic Efficiency

Kaldor-Hicks improvement and Pareto improvement are fundamental concepts in economic efficiency, measuring welfare changes in resource allocation. A Pareto improvement occurs when at least one individual benefits without making anyone worse off, representing a strict efficiency gain. Kaldor-Hicks improvement allows for potential compensation, where winners could theoretically compensate losers, enabling more flexible criteria for evaluating economic policies and efficiency.

Defining Pareto Improvement

Pareto improvement occurs when a change benefits at least one individual without making anyone else worse off, representing an efficient allocation of resources. This concept is fundamental in welfare economics, ensuring that no participant's standing is diminished by a policy shift or economic transaction. Unlike Kaldor-Hicks improvement, Pareto improvements require unanimous gains or neutrality, making them a stricter criterion for evaluating economic efficiency.

Understanding Kaldor-Hicks Improvement

Kaldor-Hicks improvement occurs when the benefits to winners exceed the losses to losers, enabling potential compensation even if no actual compensation happens, contrasting with the Pareto improvement that requires making at least one individual better off without making anyone worse off. This concept is fundamental in welfare economics for assessing policy changes where total social welfare increases despite some negative impacts. Kaldor-Hicks efficiency allows for more flexible decision-making in cost-benefit analysis by focusing on net gains rather than strict individual improvement.

Key Differences Between Pareto and Kaldor-Hicks

Pareto improvement occurs when at least one individual benefits without making anyone worse off, ensuring unanimous gains and maintaining optimal allocative efficiency. Kaldor-Hicks improvement allows for reallocations where winners gain more than losers lose, enabling potential compensation without requiring actual or immediate compensation, thus promoting overall efficiency in scenarios where Pareto improvements are impossible. The key difference lies in Pareto's strict non-harm criterion versus Kaldor-Hicks' efficiency-based criterion that tolerates some losses if overall net benefits increase.

Practical Examples of Pareto Improvement

Pareto improvement occurs when a change benefits at least one individual without making others worse off, exemplified by a policy that lowers taxes for middle-income families while maintaining current benefits for low-income earners. In contrast, Kaldor-Hicks improvement allows for net gains even if some individuals are disadvantaged, as seen in infrastructure projects where winners' gains could theoretically compensate losers, though actual compensation may not occur. Practical examples of Pareto improvements include redistributing resources through targeted social programs that uplift disadvantaged groups without reducing support for others, ensuring all affected parties experience non-negative outcomes.

Real-World Applications of Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency

Kaldor-Hicks improvement allows for policy changes where winners could theoretically compensate losers, which is particularly useful in cost-benefit analyses of infrastructure projects and environmental regulations. Unlike Pareto improvements, which require no one to be worse off, Kaldor-Hicks efficiency accepts trade-offs that enable practical decision-making in real-world scenarios involving public goods and externalities. This approach is widely applied in economic policy formulation, urban planning, and regulatory impact assessments to maximize overall social welfare despite distributional disparities.

Limitations of Pareto Criterion

The Pareto criterion faces limitations as it requires changes to benefit at least one individual without harming others, making many real-world policy decisions impractical due to inevitable trade-offs. Kaldor-Hicks improvement addresses this by allowing for compensations where winners could theoretically compensate losers, enabling more flexible evaluations of socio-economic changes. This approach broadens analysis but introduces challenges in measuring and ensuring actual compensation, often critiqued for overlooking distributional equity.

Critiques of Kaldor-Hicks Approach

The Kaldor-Hicks approach faces critiques due to its potential to justify policies that harm some individuals while benefiting others, as it does not require actual compensation for losers. This method may overlook distributional equity and ignore significant welfare losses experienced by disadvantaged groups. Critics argue that reliance on hypothetical compensation can lead to socially divisive outcomes and undermine genuine social welfare improvements compared to the stricter Pareto improvement criterion.

Policy Implications: Choosing Between Criteria

Kaldor-Hicks improvement allows for policies where winners could theoretically compensate losers, enabling broader economic reforms despite some individual losses, making it suitable for large-scale policy shifts with measurable net benefits. Pareto improvement requires changes to benefit some without harming others, restricting policy options to universally beneficial reforms but ensuring no party is disadvantaged. Policymakers often prefer Kaldor-Hicks criteria for practical decision-making in complex economic environments, while Pareto improvements guide incremental, risk-averse adjustments focusing on unanimous gains.

Conclusion: Balancing Efficiency and Equity

Kaldor-Hicks improvement allows for efficiency gains by permitting some individuals to be worse off if the overall benefits outweigh losses, while Pareto improvement requires that no one is harmed and at least one person benefits, emphasizing equity. Balancing these criteria involves recognizing that Kaldor-Hicks focuses on maximizing total social welfare but may sacrifice fairness, whereas Pareto prioritizes equity but often limits achievable efficiency gains. Effective policy decisions often seek a compromise by incorporating compensation mechanisms to address disparities highlighted in Kaldor-Hicks scenarios while striving for Pareto improvements when possible.

Kaldor-Hicks improvement Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com