A bail-out is financial support provided to a company or country facing severe distress to prevent collapse and stabilize the economy. This intervention often comes from governments or financial institutions and aims to protect jobs, restore confidence, and avoid wider financial crises. Discover how bail-outs impact your investments and the broader market in the rest of this article.

Table of Comparison

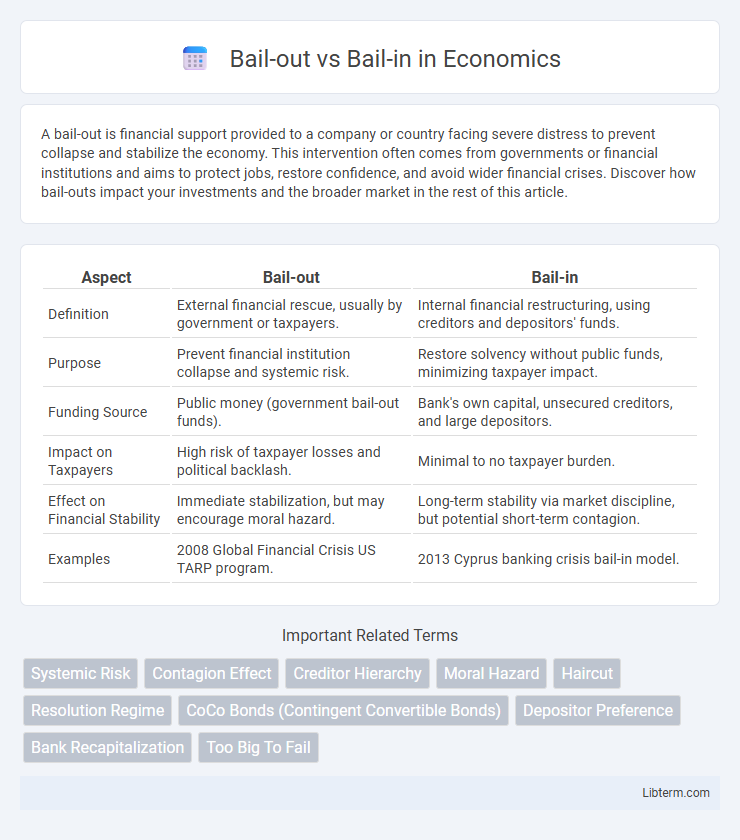

| Aspect | Bail-out | Bail-in |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | External financial rescue, usually by government or taxpayers. | Internal financial restructuring, using creditors and depositors' funds. |

| Purpose | Prevent financial institution collapse and systemic risk. | Restore solvency without public funds, minimizing taxpayer impact. |

| Funding Source | Public money (government bail-out funds). | Bank's own capital, unsecured creditors, and large depositors. |

| Impact on Taxpayers | High risk of taxpayer losses and political backlash. | Minimal to no taxpayer burden. |

| Effect on Financial Stability | Immediate stabilization, but may encourage moral hazard. | Long-term stability via market discipline, but potential short-term contagion. |

| Examples | 2008 Global Financial Crisis US TARP program. | 2013 Cyprus banking crisis bail-in model. |

Understanding Bail-Out and Bail-In: Key Definitions

Bail-out refers to financial support provided by external sources, such as governments, to rescue a failing institution and prevent systemic collapse, typically using taxpayer funds. Bail-in involves restructuring a distressed company's obligations by converting its debt into equity or writing down liabilities, thereby forcing creditors and depositors to absorb losses instead of relying on public funds. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for grasping how financial crises are managed to maintain stability and protect economic interests.

Historical Context: Evolution of Financial Rescue Mechanisms

The evolution of financial rescue mechanisms reflects a shift from government-funded bail-outs, prominently seen during the 2008 global financial crisis, to bail-ins, which emerged as a regulatory response to reduce taxpayer burden by imposing losses directly on creditors and shareholders. Early bail-outs primarily involved central banks and governments injecting capital to stabilize failing banks, exemplified by the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in the United States. In contrast, bail-ins gained prominence post-2010 with frameworks like the European Union's Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), emphasizing internal recapitalization to enhance financial system resilience.

How Bail-Outs Work: Processes and Examples

Bail-outs involve external financial assistance, typically from government or international institutions, to stabilize failing companies or financial sectors by injecting capital or guarantees. This process often includes purchasing distressed assets or providing emergency loans to restore confidence and liquidity, as seen in the 2008 global financial crisis with the U.S. Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). The goal is to prevent systemic collapse by supporting critical institutions without immediate losses to creditors or shareholders.

The Mechanics of Bail-Ins Explained

Bail-ins involve restructuring a failing financial institution's liabilities by converting creditor claims into equity, effectively using the bank's own resources to restore capital without public funds. This mechanism prioritizes subordinated debt and large depositors, who absorb losses before taxpayer intervention, maintaining systemic stability while minimizing moral hazard. Unlike bail-outs, bail-ins enforce loss-sharing among internal stakeholders, enhancing market discipline and reducing the burden on government budgets during financial crises.

Comparing Bail-Outs and Bail-Ins: Key Differences

Bail-outs involve external financial support, typically government funds, to rescue failing institutions, preserving stability and preventing systemic risks. Bail-ins require internal recapitalization by converting creditors' and depositors' claims into equity, minimizing taxpayer burden and promoting market discipline. The key differences lie in sources of funding, impact on public finances, and implications for stakeholders' risk exposure.

Impact on Taxpayers: Who Bears the Financial Burden?

Bail-outs typically place the financial burden on taxpayers as governments use public funds to rescue failing institutions, often leading to increased national debt or higher taxes. In contrast, bail-ins shift the financial responsibility to the institution's creditors and depositors, minimizing direct taxpayer exposure by restructuring liabilities internally. The choice between bail-out and bail-in significantly influences public perception and economic stability, with bail-ins promoting greater accountability among financial stakeholders.

Effects on Banks, Investors, and Creditors

Bail-outs provide external financial support to banks, stabilizing their operations and protecting investors from immediate losses but often at the taxpayers' expense, which can create moral hazard. Bail-ins force banks' creditors and sometimes large depositors to absorb losses by converting debt into equity or writing down claims, directly impacting investors and creditors but preserving taxpayer funds. This internal recapitalization approach promotes more disciplined risk management among banks and aligns the cost of failure with those who invested in the institution.

Regulatory Frameworks Governing Bail-Outs and Bail-Ins

Regulatory frameworks governing bail-outs and bail-ins vary significantly, reflecting their distinct approaches to financial crisis management. Bail-outs, typically involving government-funded rescues, are regulated by emergency financial assistance laws and central bank mandates to maintain systemic stability and protect taxpayers. In contrast, bail-ins are governed by resolution regimes such as the EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) and the U.S. Dodd-Frank Act, which empower regulatory authorities to restructure failing banks by imposing losses on shareholders and creditors without direct public funds.

Case Studies: Notable Bail-Outs and Bail-Ins in Recent History

The 2008 financial crisis exemplified a major bail-out when the U.S. government injected $700 billion into failing banks and automotive companies, notably rescuing entities like AIG and General Motors to prevent systemic collapse. In contrast, the 2013 Cyprus banking crisis highlighted a prominent bail-in, where creditors and depositors faced losses to recapitalize banks, marking a shift toward internal funding in financial rescues. The Greek debt crisis also featured complex bail-in mechanisms combined with international bail-outs, illustrating evolving approaches to sovereign and banking sector stability.

Future Outlook: Trends and Policy Debates on Financial Rescues

Future outlook on financial rescues highlights a growing preference for bail-ins over bail-outs due to their emphasis on reducing taxpayer burden and enhancing financial sector accountability. Emerging trends include increased regulatory frameworks mandating bail-in mechanisms, such as the EU's Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), which aim to strengthen systemic resilience and limit moral hazard. Policy debates continue to focus on balancing financial stability with investor protections while fostering transparency and efficient risk management in crisis interventions.

Bail-out Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com