Fiscal multiplier theory explores how government spending influences overall economic output, measuring the ratio of change in GDP to the initial change in fiscal policy. It highlights the potential for increased public expenditure to stimulate demand, boost employment, and accelerate growth during economic downturns. Discover how understanding this concept can enhance your insights into economic policy and its real-world impact by reading the rest of the article.

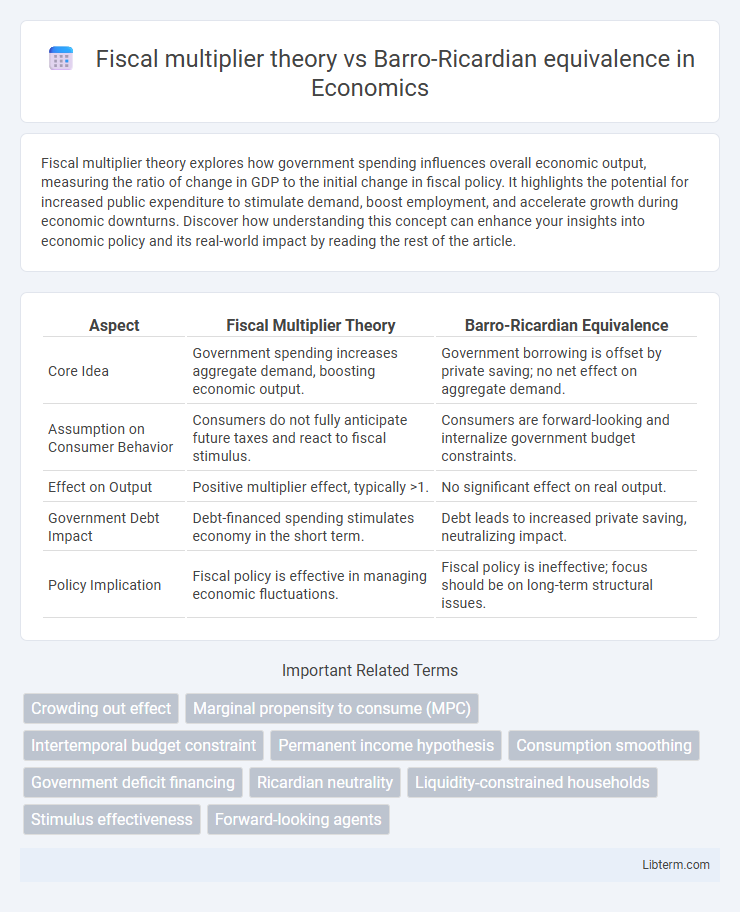

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Fiscal Multiplier Theory | Barro-Ricardian Equivalence |

|---|---|---|

| Core Idea | Government spending increases aggregate demand, boosting economic output. | Government borrowing is offset by private saving; no net effect on aggregate demand. |

| Assumption on Consumer Behavior | Consumers do not fully anticipate future taxes and react to fiscal stimulus. | Consumers are forward-looking and internalize government budget constraints. |

| Effect on Output | Positive multiplier effect, typically >1. | No significant effect on real output. |

| Government Debt Impact | Debt-financed spending stimulates economy in the short term. | Debt leads to increased private saving, neutralizing impact. |

| Policy Implication | Fiscal policy is effective in managing economic fluctuations. | Fiscal policy is ineffective; focus should be on long-term structural issues. |

Introduction to Fiscal Multiplier Theory

Fiscal Multiplier Theory examines how changes in government spending influence overall economic output, emphasizing that an increase in fiscal expenditure typically leads to a proportionally larger increase in GDP. This theory contrasts with Barro-Ricardian Equivalence, which posits that consumers anticipate future taxes linked to government debt, thus neutralizing the impact of fiscal policy on aggregate demand. Understanding the fiscal multiplier effect is crucial for assessing the efficacy of expansionary fiscal policies in stimulating economic growth.

Fundamentals of Barro-Ricardian Equivalence

The Barro-Ricardian equivalence theory posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because rational agents anticipate future taxes to repay debt and therefore increase savings to offset government deficits. This contrasts with the fiscal multiplier theory, which suggests that government spending boosts aggregate demand and output, particularly when there is idle capacity. Central to Barro-Ricardian equivalence are assumptions of perfect capital markets, intergenerational altruism, and fully rational forward-looking agents.

Key Assumptions Underpinning Fiscal Multiplier

The fiscal multiplier theory assumes that government spending directly increases aggregate demand by raising consumption and investment, assuming incomplete crowding-out and sticky prices. Key assumptions include the presence of underutilized resources and liquidity-constrained consumers who respond to fiscal stimulus by spending rather than saving. In contrast, the Barro-Ricardian equivalence posits that rational agents anticipate future taxes to pay for government debt, leading them to save any fiscal transfers, thus nullifying the multiplier effect.

Core Principles of Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian Equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future tax liabilities resulting from government borrowing, leading them to increase savings and neutralize the impact of fiscal stimulus on aggregate demand. This theory assumes forward-looking behavior, perfect capital markets, and intergenerational altruism, where individuals consider the welfare of future generations when making consumption decisions. In contrast, fiscal multiplier theory emphasizes the short-term impact of government spending on output, suggesting that increased fiscal deficits can stimulate economic activity without immediate offsetting increases in private saving.

Comparative Analysis: Multiplier vs. Equivalence

Fiscal multiplier theory asserts that government spending increases aggregate demand and output, amplifying economic growth through a multiplier effect. The Barro-Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future taxes from government borrowing and thus increase savings, neutralizing fiscal stimulus impact. Comparative analysis reveals that while the multiplier effect emphasizes short-term demand-driven growth, Ricardian equivalence stresses intertemporal budget constraints that limit fiscal policy effectiveness.

Policy Implications: Stimulus Effectiveness

Fiscal multiplier theory asserts that government spending increases aggregate demand, stimulating economic output and justifying fiscal stimulus during recessions. Barro-Ricardian equivalence argues that consumers anticipate future taxes from government deficits, offsetting stimulus effects by increasing savings, thus reducing policy effectiveness. Policymakers must balance stimulus measures with long-term debt considerations, as the actual impact on economic growth depends on public expectations and fiscal credibility.

Empirical Evidence and Real-World Examples

Empirical evidence on the fiscal multiplier theory shows varied impacts of government spending on economic output, with multipliers generally above one during recessions, notably seen in the U.S. stimulus of 2009. In contrast, the Barro-Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future taxes from government debt, leading to muted effects of fiscal policy; however, real-world examples like Japan's persistent debt challenge this view. Studies often highlight that liquidity constraints and myopic behavior weaken Ricardian predictions, underscoring the contextual significance of fiscal multipliers in policy effectiveness.

Theoretical Critiques and Limitations

Fiscal multiplier theory faces critique for assuming short-term government spending increases output without accounting for crowding-out effects or long-term debt sustainability, potentially overestimating fiscal policy effectiveness. Barro-Ricardian equivalence argues that consumers internalize government budget constraints, implying fiscal expansions do not affect aggregate demand, but this relies on strong assumptions like perfect capital markets, infinite horizons, and rational expectations rarely met in practice. Both frameworks struggle with empirical validation and heterogeneity across economic contexts, highlighting limits in predicting real-world fiscal policy outcomes.

Macroeconomic Contexts Shaping Applicability

The fiscal multiplier theory highlights how government spending can stimulate aggregate demand, influencing output and employment levels, especially in recessionary macroeconomic contexts characterized by slack resources and liquidity constraints. In contrast, the Barro-Ricardian equivalence posits that rational agents anticipate future taxation from current government deficits, neutralizing fiscal policy effects in environments with perfect capital markets and forward-looking consumers. The applicability of these theories depends heavily on macroeconomic variables such as interest rates, inflation expectations, and agents' access to credit, which shape the effectiveness of fiscal interventions in different economic conditions.

Conclusion: Bridging Theory and Policy Debate

Fiscal multiplier theory emphasizes that government spending can stimulate economic output by increasing aggregate demand, particularly in times of recession, suggesting active fiscal policy is effective. Barro-Ricardian equivalence argues that rational consumers anticipate future taxes from government debt, neutralizing the impact of fiscal stimulus on overall demand. Bridging these perspectives, empirical research indicates the size of fiscal multipliers varies with economic conditions and institutional settings, highlighting the need for tailored policy approaches that consider both behavioral responses and macroeconomic contexts.

Fiscal multiplier theory Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com