The Scitovsky Criterion evaluates social welfare by comparing two economic states to ensure mutual improvement and avoid paradoxes in welfare judgments. It addresses limitations of the Kaldor-Hicks Criterion by requiring that winners could compensate losers and vice versa, ensuring more consistent welfare comparisons. Explore the full article to understand how this criterion impacts economic policy and decision-making.

Table of Comparison

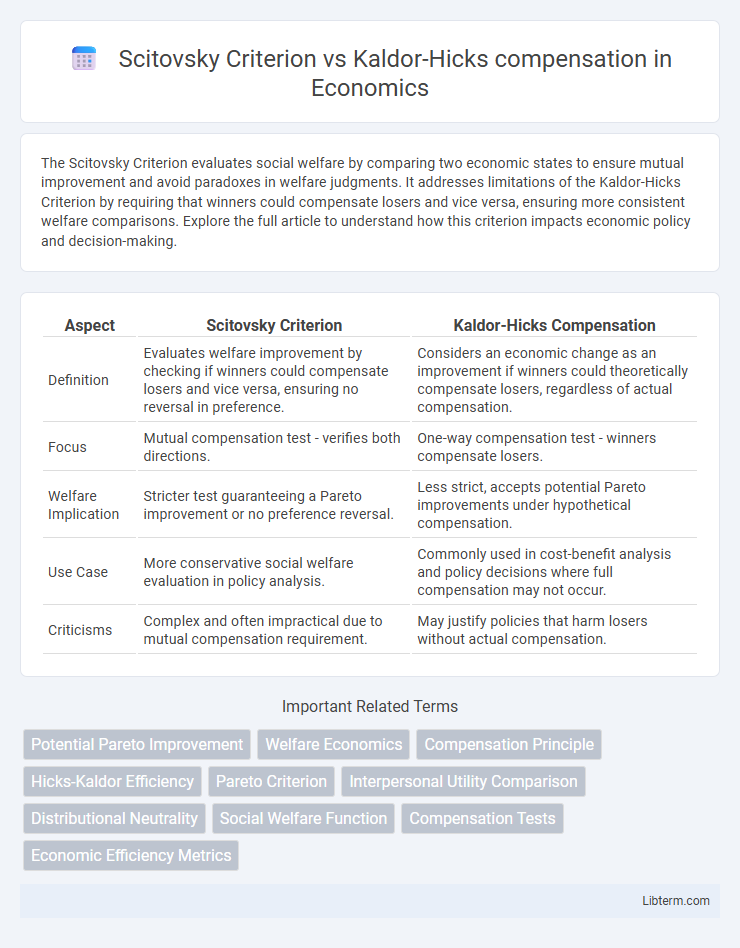

| Aspect | Scitovsky Criterion | Kaldor-Hicks Compensation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Evaluates welfare improvement by checking if winners could compensate losers and vice versa, ensuring no reversal in preference. | Considers an economic change as an improvement if winners could theoretically compensate losers, regardless of actual compensation. |

| Focus | Mutual compensation test - verifies both directions. | One-way compensation test - winners compensate losers. |

| Welfare Implication | Stricter test guaranteeing a Pareto improvement or no preference reversal. | Less strict, accepts potential Pareto improvements under hypothetical compensation. |

| Use Case | More conservative social welfare evaluation in policy analysis. | Commonly used in cost-benefit analysis and policy decisions where full compensation may not occur. |

| Criticisms | Complex and often impractical due to mutual compensation requirement. | May justify policies that harm losers without actual compensation. |

Introduction to Welfare Economics Criteria

Scitovsky Criterion refines welfare economics by requiring mutual compensation between winners and losers of a policy change, ensuring an outcome preferred in both forward and reverse directions. Kaldor-Hicks compensation allows welfare improvements if winners could theoretically compensate losers, even without actual compensation, prioritizing Pareto improvements in resource allocation. Both criteria evaluate efficiency in policy changes but differ in their stringency and practical applicability in welfare economics analysis.

Defining the Scitovsky Criterion

The Scitovsky Criterion defines a welfare improvement by requiring that a change in allocation makes at least one individual better off without making anyone worse off, and that the gain can be reversed by compensating those who lose. This criterion refines Kaldor-Hicks efficiency by emphasizing the potential for mutual compensation, ensuring any Pareto improvement is genuine and not just an aggregate gain. It balances equity and efficiency by avoiding changes that might appear beneficial under Kaldor-Hicks but fail the reciprocal compensation test.

Understanding the Kaldor-Hicks Compensation Principle

The Kaldor-Hicks compensation principle evaluates economic efficiency by determining if the winners from a policy change could hypothetically compensate the losers, ensuring a net gain in social welfare without requiring actual compensation. This principle is less stringent than the Scitovsky criterion, as it does not demand that the losers be better off post-compensation, only that potential compensation is possible. Understanding Kaldor-Hicks helps in assessing policies where total benefits exceed total costs, emphasizing aggregate improvements over individual equity.

Core Assumptions of Both Criteria

The Scitovsky Criterion assumes that welfare improvements require mutual gain where both parties prefer the change, emphasizing reversible changes to avoid welfare paradoxes, while the Kaldor-Hicks criterion relies on potential compensation, accepting improvements if winners could hypothetically compensate losers. Both criteria address efficiency in welfare economics but diverge in their assumptions about compensation feasibility and welfare reversibility. Scitovsky's criterion requires actual or at least possible mutual compensation, whereas Kaldor-Hicks assumes compensation potential without necessitating reversibility of the change.

Measurement of Gains and Losses

The Scitovsky Criterion measures gains and losses by directly comparing the compensation each party requires to be as well-off after a change, emphasizing mutual compensability for improving social welfare. Kaldor-Hicks compensation evaluates gains and losses through potential compensation, where an allocation is considered efficient if the winners could theoretically compensate the losers, regardless of actual compensation occurring. While Scitovsky requires compensation to be both ways to avoid conflicting conclusions, Kaldor-Hicks accepts a one-sided compensation feasibility, focusing more on aggregate efficiency.

Resolving the Compensation Test Paradox

The Scitovsky Criterion refines the Kaldor-Hicks compensation test by requiring mutual compensation to establish a welfare improvement, thereby resolving the compensation test paradox where Kaldor-Hicks could indicate conflicting outcomes. It mandates that a policy is only deemed efficient if those who gain could hypothetically compensate the losers and vice versa, avoiding contradictory conclusions about social welfare gain. This reciprocal requirement enhances consistency in welfare comparisons and improves policy evaluations in cost-benefit analysis.

Efficiency and Distributional Concerns

The Scitovsky Criterion refines efficiency analysis by requiring that any proposed change is preferred in both forward and reverse tests, ensuring mutual benefit and addressing distributional fairness more rigorously than Kaldor-Hicks compensation, which only demands that winners' gains can theoretically compensate losers without actual compensation. This makes the Scitovsky Criterion more sensitive to potential welfare reversals and equity implications in economic policy evaluation. While Kaldor-Hicks focuses on Pareto improvement through compensability, the Scitovsky approach integrates distributional concerns explicitly, emphasizing more robust efficiency assessments in welfare economics.

Practical Applications in Policy Analysis

Scitovsky Criterion emphasizes mutual gains in policy changes, requiring that beneficiaries could potentially compensate those harmed, ensuring Pareto improvements in welfare analysis. In contrast, Kaldor-Hicks compensation focuses on net gains without actual compensation, widely applied in cost-benefit analysis to justify policies when total benefits exceed total costs. Policymakers prefer Kaldor-Hicks for its practicality in evaluating infrastructure projects and regulatory impacts, while Scitovsky Criterion provides a stricter standard often used in theoretical welfare economics.

Criticisms and Limitations

The Scitovsky Criterion faces criticism for its practical challenges in achieving reversible welfare improvements, as it requires that winners could theoretically compensate losers without actual transfers. Kaldor-Hicks compensation is often limited by its assumption of feasible compensation without enforcing redistribution, leading to potential welfare losses despite aggregate gains. Both criteria are criticized for neglecting distributional equity and relying on hypothetical compensation that may not occur in reality.

Conclusion: Comparative Insights

The Scitovsky Criterion refines welfare comparisons by requiring mutual compensation, ensuring changes benefit one group without harming another, while Kaldor-Hicks compensation only requires potential winners could compensate losers, without actual compensation. This makes Scitovsky more stringent in assessing Pareto improvements and resolves paradoxes inherent in Kaldor-Hicks tests. In practical policy evaluation, Scitovsky's approach offers stronger guarantees of social welfare improvement but at the cost of increased complexity and restrictiveness compared to Kaldor-Hicks compensation.

Scitovsky Criterion Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com