Real Business Cycle (RBC) theory explains economic fluctuations through real shocks such as changes in technology or resource availability, rather than monetary factors. It emphasizes how these real shocks affect productivity, labor supply, and investment decisions, leading to variations in output and employment. Discover how understanding RBC can provide valuable insights into managing economic cycles by reading the rest of the article.

Table of Comparison

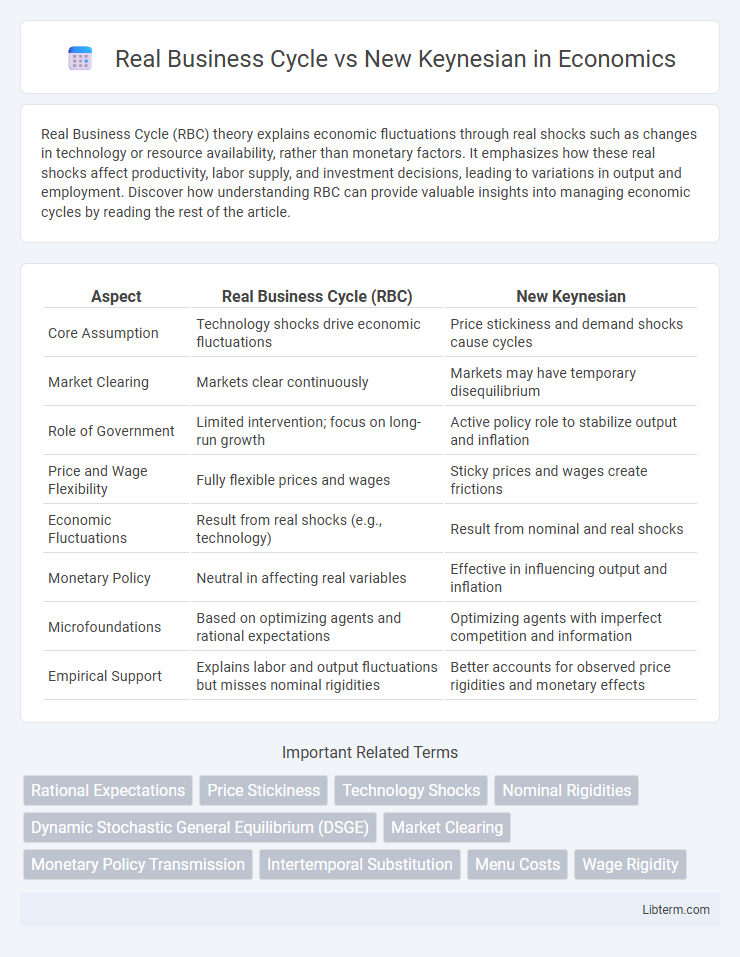

| Aspect | Real Business Cycle (RBC) | New Keynesian |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | Technology shocks drive economic fluctuations | Price stickiness and demand shocks cause cycles |

| Market Clearing | Markets clear continuously | Markets may have temporary disequilibrium |

| Role of Government | Limited intervention; focus on long-run growth | Active policy role to stabilize output and inflation |

| Price and Wage Flexibility | Fully flexible prices and wages | Sticky prices and wages create frictions |

| Economic Fluctuations | Result from real shocks (e.g., technology) | Result from nominal and real shocks |

| Monetary Policy | Neutral in affecting real variables | Effective in influencing output and inflation |

| Microfoundations | Based on optimizing agents and rational expectations | Optimizing agents with imperfect competition and information |

| Empirical Support | Explains labor and output fluctuations but misses nominal rigidities | Better accounts for observed price rigidities and monetary effects |

Introduction to Real Business Cycle and New Keynesian Economics

Real Business Cycle (RBC) theory emphasizes technology shocks as the primary driver of economic fluctuations, modeling the economy with rational agents optimizing intertemporally in a frictionless market. New Keynesian Economics incorporates price and wage rigidities, imperfect competition, and market imperfections, explaining short-run fluctuations and the effectiveness of monetary policy in stabilizing output. Both frameworks use dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models but differ in assumptions about market imperfections and sources of economic variability.

Historical Development of RBC and New Keynesian Theories

The Real Business Cycle (RBC) theory, developed in the 1980s by economists like Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott, emphasizes technology shocks as the primary driver of economic fluctuations, relying on microeconomic foundations and rational expectations. The New Keynesian framework emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s, incorporating price and wage rigidities to address market imperfections neglected by RBC models, with key contributors such as Gregory Mankiw and David Romer. Both theories revolutionized macroeconomics by integrating dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models but diverge on the roles of market frictions and government intervention in stabilizing the economy.

Core Assumptions of Real Business Cycle Models

Real Business Cycle (RBC) models assume that economic fluctuations arise from real shocks, such as technology changes, rather than monetary disturbances, emphasizing rational expectations and market clearing with flexible prices and wages. These models posit that all agents optimize intertemporally, adjusting labor supply and capital accumulation in response to productivity shocks, leading to efficient and Pareto-optimal outcomes. RBC frameworks contrast sharply with New Keynesian models, which incorporate nominal rigidities and price stickiness, resulting in imperfect market adjustments and the necessity of policy interventions.

Key Features of New Keynesian Economics

New Keynesian economics emphasizes price stickiness and imperfect competition, which cause market failures and short-run economic fluctuations. It incorporates rational expectations and nominal rigidities, explaining why monetary and fiscal policies can have real effects on output and employment. The model contrasts with Real Business Cycle theory by allowing for demand-side shocks and policy interventions to stabilize the economy.

Differences in Policy Implications

Real Business Cycle (RBC) models emphasize supply-side shocks and suggest limited government intervention since fluctuations are viewed as efficient market responses, whereas New Keynesian models highlight price stickiness and market imperfections, advocating active monetary and fiscal policies to stabilize output and inflation. RBC theories argue that policy interventions may distort natural market adjustments, while New Keynesian approaches support counter-cyclical measures such as interest rate adjustments and fiscal stimulus to mitigate recessions. This fundamental difference leads to contrasting prescriptions regarding the role of central banks and government in managing economic cycles.

The Role of Shocks and Market Adjustments

Real Business Cycle (RBC) theory attributes economic fluctuations primarily to technology shocks that directly affect productivity and output, emphasizing fully flexible markets that adjust instantaneously to restore equilibrium. In contrast, New Keynesian models incorporate nominal rigidities such as price and wage stickiness, causing slower market adjustments and persistent effects of demand and supply shocks on output and employment. These differences highlight how RBC focuses on real shocks and rapid adjustments, while New Keynesian economics accounts for frictions that produce prolonged deviations from full employment equilibrium.

Microfoundations and Rational Expectations

Real Business Cycle (RBC) models emphasize microfoundations grounded in optimizing behavior of agents facing technology shocks, while New Keynesian models incorporate nominal rigidities alongside these microfoundations to explain price stickiness. Both frameworks assume rational expectations, ensuring agents form forecasts based on all available information and model-consistent beliefs. New Keynesian models extend RBC by integrating imperfect competition and adjustment costs, allowing for short-run fluctuations driven by monetary policy effects.

Empirical Evidence and Model Performance

Empirical evidence reveals that New Keynesian models better capture wage and price rigidities, aligning closely with observed economic fluctuations and inflation persistence, whereas Real Business Cycle (RBC) models primarily emphasize technology shocks with limited explanatory power on short-term dynamics. New Keynesian frameworks demonstrate superior model performance in replicating monetary policy impacts and providing realistic impulse response functions, outperforming RBC models in matching macroeconomic data variability. The integration of nominal rigidities and microfoundations in New Keynesian models enhances their empirical relevance, making them more consistent with observed business cycle phenomena compared to the purely real shocks driving RBC models.

Criticisms and Limitations of Both Approaches

Real Business Cycle (RBC) models often face criticism for their heavy reliance on technology shocks as the primary drivers of economic fluctuations, overlooking demand-side factors and failing to account for observed price stickiness and unemployment dynamics. New Keynesian models, while incorporating price rigidity and nominal frictions, are criticized for relying on assumptions like rational expectations and sometimes ad hoc price adjustment mechanisms, which may not fully capture real-world complexities. Both approaches struggle with explaining large, persistent deviations from equilibrium without resorting to exogenous shocks or rigid calibrations, limiting their empirical validity and policy relevance.

Future Directions in Macroeconomic Theory

Future directions in macroeconomic theory emphasize integrating Real Business Cycle (RBC) models' microfoundations with New Keynesian frameworks' nominal rigidities to better capture economic fluctuations. Research focuses on enhancing heterogeneous agent models and incorporating financial frictions to improve predictions of business cycles and policy impacts. Advances in computational methods enable more precise simulations of dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models, fostering a deeper understanding of macroeconomic dynamics under uncertainty.

Real Business Cycle Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com