Non-price rationing allocates scarce resources without adjusting prices, relying instead on factors such as waiting times, quality, or access restrictions to manage demand. This approach often emerges in markets where price controls exist or where fairness and equity are prioritized over market efficiency. Explore the rest of the article to understand how non-price rationing impacts consumer behavior and market dynamics.

Table of Comparison

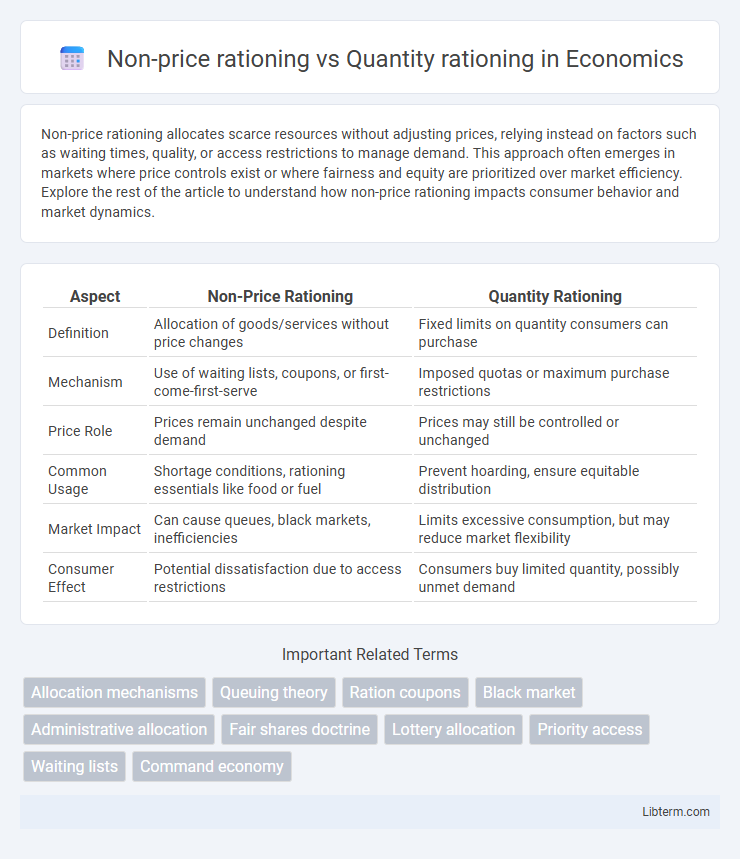

| Aspect | Non-Price Rationing | Quantity Rationing |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Allocation of goods/services without price changes | Fixed limits on quantity consumers can purchase |

| Mechanism | Use of waiting lists, coupons, or first-come-first-serve | Imposed quotas or maximum purchase restrictions |

| Price Role | Prices remain unchanged despite demand | Prices may still be controlled or unchanged |

| Common Usage | Shortage conditions, rationing essentials like food or fuel | Prevent hoarding, ensure equitable distribution |

| Market Impact | Can cause queues, black markets, inefficiencies | Limits excessive consumption, but may reduce market flexibility |

| Consumer Effect | Potential dissatisfaction due to access restrictions | Consumers buy limited quantity, possibly unmet demand |

Introduction to Rationing Mechanisms

Rationing mechanisms allocate scarce resources when demand exceeds supply, with non-price rationing distributing goods through criteria other than price, such as waiting lists, lotteries, or priority groups, while quantity rationing sets a fixed limit on the amount each participant can obtain. Non-price rationing avoids price discrimination but may lead to inefficiencies like black markets or long queues. Quantity rationing controls consumption directly but can result in unmet demand or reduced incentives for suppliers to increase production.

Defining Non-Price Rationing

Non-price rationing allocates scarce resources or goods without using price as a controlling factor, often through mechanisms like queues, lotteries, or eligibility criteria. This contrasts with quantity rationing, which restricts the amount of goods available while allowing price to adjust. Non-price rationing aims to manage demand and distribution fairly during shortages when price increases are undesirable or ineffective.

Understanding Quantity Rationing

Quantity rationing occurs when products or services are limited in supply, forcing sellers to allocate fixed quantities to buyers regardless of price. This method contrasts with non-price rationing, which uses non-monetary criteria such as waiting lists or coupons to distribute scarce resources. Understanding quantity rationing is crucial for analyzing market inefficiencies and consumer access during shortages, as it directly restricts the amount consumers can purchase despite willingness to pay.

Key Differences Between Non-Price and Quantity Rationing

Non-price rationing allocates scarce resources based on factors other than price, such as time, effort, or eligibility criteria, whereas quantity rationing restricts the amount of goods or services available to consumers regardless of their willingness to pay. Key differences include the mechanism of allocation, with non-price rationing often using queues or lotteries, while quantity rationing imposes fixed limits on consumption. Non-price rationing impacts consumer behavior by creating non-monetary barriers, whereas quantity rationing directly limits the volume purchased, affecting supply distribution efficiency.

Real-World Examples of Non-Price Rationing

Non-price rationing occurs when resources or goods are allocated without changing the price, often through mechanisms like waiting lists, lotteries, or quotas, contrasting with quantity rationing where supply restrictions directly limit availability. Real-world examples include organ transplants assigned via complex eligibility criteria and waiting lists, and limited edition products distributed through lotteries to manage demand without price increases. In contrast, quantity rationing is commonly seen during fuel shortages, where fuel stations impose strict purchase limits per customer to control consumption.

Practical Applications of Quantity Rationing

Quantity rationing is commonly applied in situations where limited resources must be distributed fairly, such as during fuel shortages or vaccine allocations. It prevents market prices from rising excessively and ensures access based on predetermined quotas, often regulated by government or institutions. This method helps maintain social equity and stability when demand surpasses supply.

Impacts on Market Efficiency

Non-price rationing methods, such as queuing or favoritism, often lead to allocative inefficiencies by causing mismatches between demand and supply, resulting in lost consumer surplus. Quantity rationing, by limiting the amount of goods available, can create shortages and encourage black markets, further distorting market equilibrium. Both mechanisms undermine market efficiency by preventing the price system from signaling true scarcity and guiding optimal resource allocation.

Equity and Fairness in Rationing Methods

Non-price rationing allocates goods based on criteria such as merit, need, or waiting time, promoting equity by prioritizing fairness and social welfare rather than purchasing power. Quantity rationing ensures fixed limits on the amount individuals can obtain, preventing hoarding and fostering fairness through equal distribution regardless of income. Both methods address equity concerns differently: non-price rationing emphasizes subjective fairness measures, while quantity rationing enforces objective limits to promote equal access.

Challenges and Limitations of Each Approach

Non-price rationing often faces challenges such as inefficiency and discouragement of competition due to arbitrary allocation methods like queues or coupons, leading to potential shortages and black markets. Quantity rationing can limit consumer choice and create administrative burdens, as strict limits on goods or services may not reflect actual demand variations and cause dissatisfaction. Both approaches struggle to allocate resources optimally, with non-price methods risking inequity and quantity restrictions generating waste or grey markets.

Policy Implications and Conclusions

Non-price rationing methods, such as queuing or favoritism, often lead to inefficiencies like longer wait times and potential market distortions, whereas quantity rationing imposes strict limits on available supply or consumption levels. Policymakers must balance the trade-offs between administrative costs and economic welfare, recognizing that non-price rationing can cause inequities while quantity rationing may restrict market responsiveness. Effective policy design requires targeting mechanisms that minimize resource misallocation while maintaining fairness and access to essential goods or services.

Non-price rationing Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com